Building Thoughtful Organizations: GenAI Means More Decision Making

As organizations deepen the integration of AI and platform-based ecosystems into their operating models, one thing becomes increasingly clear: the more we amplify productivity, variability, and velocity through tools like AI and third-party integrations, the more semantics and ontologies become essential.

Simone Cicero

As I wrote on linkedin a few days ago – while we were having a conversation with Simon Wardley for an upcoming episode (stay tuned), he made the point that we’ve seen radical improvements in developer productivity already in the past and – every time – consistently, investing the right amount of time in decision making – which in software development often overlaps with designing good architectures – it was choice with consequences.

It’s true that with GenAI, we can virtually build and accelerate anything (code, interfaces, content, strategies). However, suppose we don’t invest and scale our capability to make sound architectural choices (both in software and organizations). In that case, speed often leads to technical debt, lower maintainability, and an increased number of wrong decisions.

The same principle applies at the organizational level. Suppose everyone uses AI tools frantically, without any strategic intent or governance. In that case, we can easily generate organizational debt—a backlog of unmade decisions and unfocused directions —and eventually, many things are built without any connection to business outcomes.

So here’s the catch: while everyone is celebrating because “we can now do more,” few understand that this doesn’t in any way reduce the need to ask the hard questions. They are: “Are we doing the right things, and are we doing them in an intentional, thoughtful, and controlled way?”

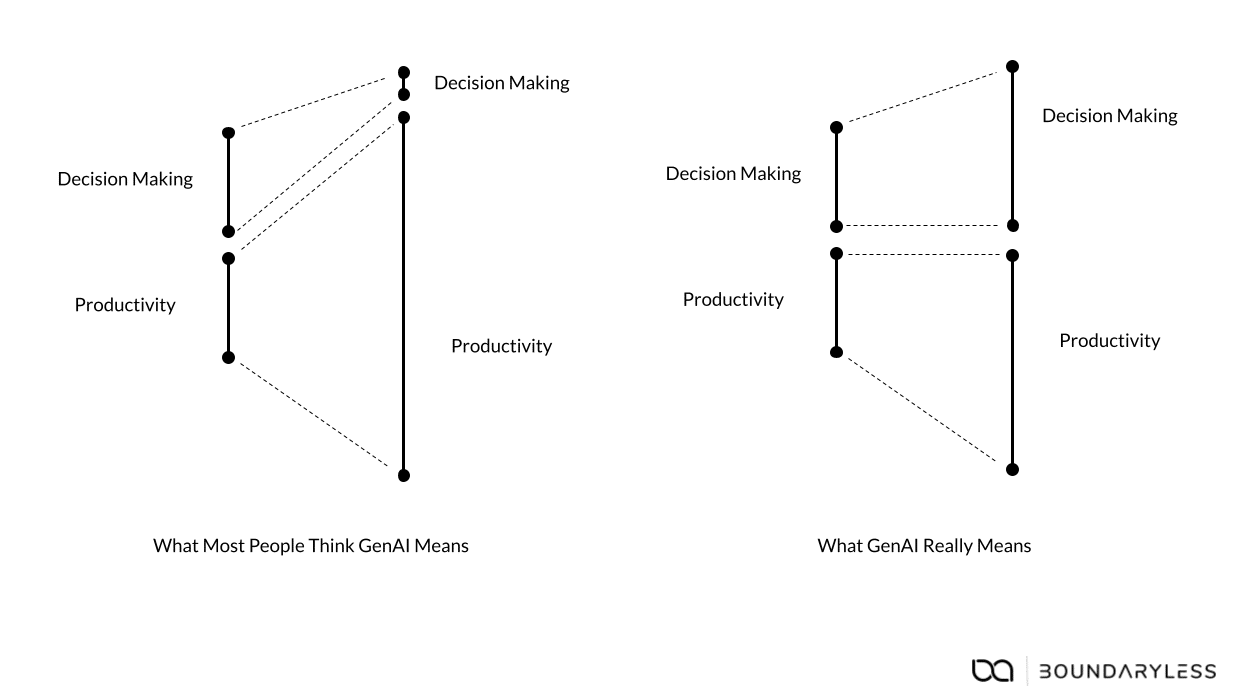

The diagram I created tells the story. Most people believe that GenAI enhances productivity and streamlines decision-making (because of “data”). However, as productivity skyrockets, if we do not grow the capability for making good decisions in parallel with productivity, and decision-making lags—or even deteriorates—our organizations are fated to fare even worse than they would without GenAI’s magic.

In a landscape where everything is suddenly buildable, we need constraints, thoughtfulness, and intention. We also need proper governance and new design models.

And most importantly, we need better ways to decide what not to build. Better, everyone has to decide what not to build autonomously.

In the past, hyperscalers like Salesforce, HubSpot, Shopify, or Amazon have based their success not strictly on features, but rather on scalable interfaces. They succeeded in bringing forth a shared ontology of workflows that has enabled a vibrant ecosystem of plugins and extensions. These systems work because participants can communicate effectively and compose productivity-enhancing solutions through interoperability.

In our recent blog post, we explored how large language models (LLMs) reinforce this lesson: to make AI work effectively, we need to give it structure. AI doesn’t just need prompts—it needs operating constraints and clarity of purpose. Interfaces and semantic affordances guide its behavior in a way that enhances collaboration and productivity.

So the question is: Should we now start designing our organizations semantically—with clear ontologies and affordances—as the singularity accelerates? Do we need to grow our capacity to understand the customers and the world so we can choose the best outcome? We believe so.

Yet, how fixed or mutable should these sensemaking languages and ontologies be? How shared or local?

This week, we curated a brilliant piece, “Connecting Dots” by John Cutler. In it, he reflects on the need to bridge strategic abstraction and local meaning-making. One is insufficient without the other, but they also struggle to communicate. You build structure and people work around it to get good work done. That’s the challenge in today’s organizational design.

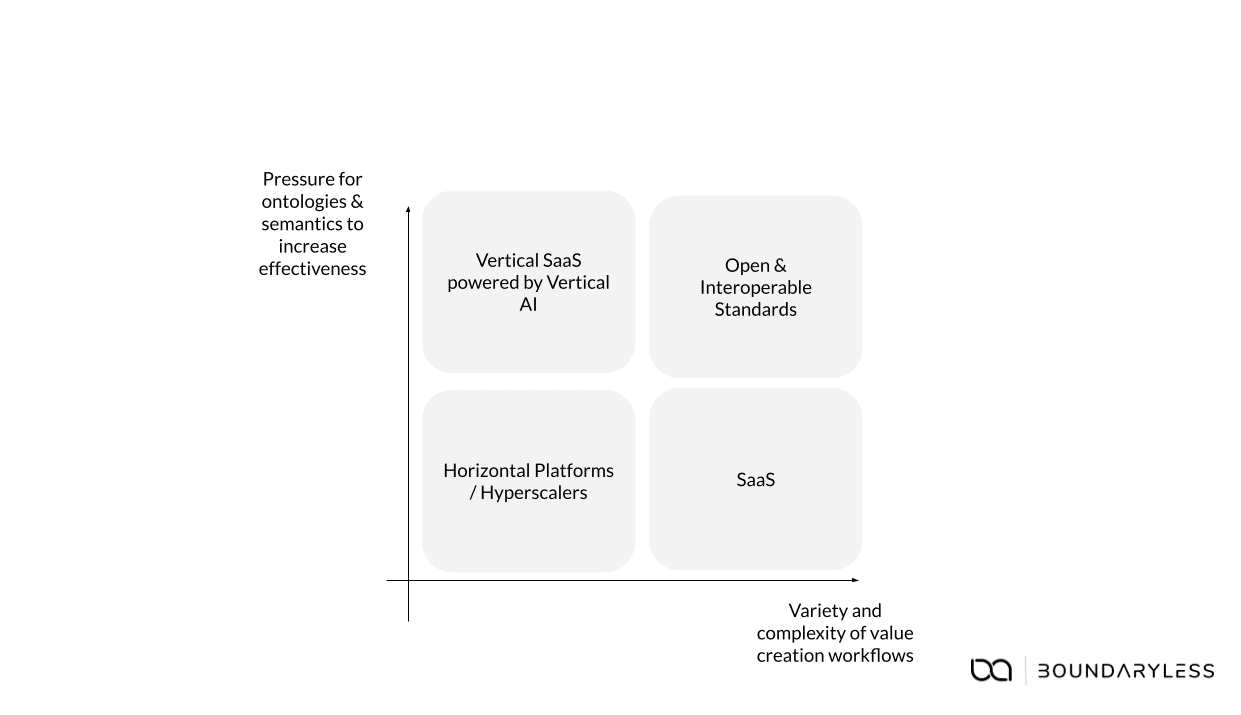

In one of our latest visual frameworks, we suggest that as complexity and interdependence grow across industries, the pressure to converge on common semantics also grows—at least in the critical layers of value creation (e.g., what constitutes a product, what “value” means in a specific collaboration, or how to represent a customer need).

We anticipate a dual motion:

- Convergence around open, semantic standards—shared definitions and patterns for collaborating at scale, especially in AI-mediated ecosystems.

- Openness and modularity at the edge—portfolios of initiatives capable of integrating and even being transformed by external input, as described in Chora’s work on evolutionary portfolios curated this week.

The key point is that as the power to build expands and AI accelerates our ability to create, our choices about what to make (and what not to) become more consequential.

If we care about AI explainability, what’s the point if we lack a common understanding of what the organization is trying to achieve?

What should we observe if we do not have the minimal critical capability to evaluate what for and the results? Be it a North Star, a business outcome, or a shared mission—clarity and intention are important.

Wendell Berry once reminded us:

“limits are not confinements but rather inducements to formal elaboration and elegance, to fullness of relationship and meaning.”

Constraints enable organizations to build responsibly and meaningfully in the face of accelerating capabilities.

This is the emerging challenge for leaders, product builders, and organizational designers: grapple with increasing capabilities by enhancing sensemaking capacities.

This is why Boundaryless is now focusing on these challenges and, most recently, we’ve released the Portfolio Map Canvas—a visual tool to help you understand your organization and its context before applying the organizational and product design frameworks we’ve developed over the years.