When Challenges Outgrow Single Organizations: from Platform Thinking to Ecosystem Orchestration

How do public and private sector leaders leverage the 3EO Framework and Portfolio Map Canvas to tackle systemic challenges that no single entity can solve alone?

Simone Cicero

Lucía Hernández

The Limits of Individual Action in a Connected World

In the past decade, we’ve witnessed remarkable transformations in how public services approach complex problems. Platform thinking has brought experiments and success stories—some of which we have also been directly involved with at Boundaryless — where central, local, or regional public authorities created digital platform initiatives that connected users, families, and professionals to complement public services by facilitating connections between players around the social economy.

Yet today, we’re reaching the natural boundaries of this first-generation approach. As we’ve learned from working with organizations worldwide, even business strategies have outgrown what any single, monolithic organization can address, regardless of its resources or mandate.

Similarly, no players in the public sector, development, or social economy can effectively address the pressing systemic challenges of our time—from healthcare system resilience to climate adaptation, from the development of sustainable tourism for cities, to economic growth or technological inclusion: Complex ecosystems need system coordination tools that can address this complexity.

Consider a typical citizen’s journey through today’s public services: each of the core services, even when well-designed as a platform, operates within an ecosystem of interrelated user needs, often involving contributions from an ecosystem of users, partners, and players of all kinds.

Even a public administrator focused on one single and isolated topic, like tourism management, will fail to achieve strategic objectives without considering mobility, residents, entrepreneurship support, and more.

It’s the same with all complex organisms: it’s like with your health if you don’t consider how all the factors fit in – like nutrition, sports, air and water quality- you won’t get healthier over time.

The result is a fragmented journey that squarely places the burden of integration on the recipient’s shoulders, as the various players optimize for their specific points of view.

This fragmentation represents a fundamental misalignment between how we have, so far, been able to orchestrate our institutions and how real-world challenges manifest. Problems like sustainable urban development or community health don’t respect organizational boundaries, yet our solutions continue to be bounded by the structures of individual agencies, departments, or companies.

From Platform Thinking to Ecosystem Orchestration

The question needs to shift from a tech or model-centric:

“How can we platform this specific service?”

to

“How can we respond to the individual needs?”

and

“How can we support and orchestrate an ecosystem of players that serve this ecosystem need?”

This transition requires thinking beyond the boundaries of a single organization: no single organization can address the challenges we face nowadays.

In recent months, our release of the Portfolio Map Canvas has enabled teams worldwide to map complex organizational systems. It revealed fascinating insights: creating adaptable organizations that deliver highly relevant services and innovations often requires different capabilities to combine unpredictably.

Take the example of urban mobility: a traditional approach might involve a transportation authority creating a platform for bus services. At the same time, a separate entity manages bike-sharing, and yet another handles ride-sharing regulations. An ecosystem approach would start by understanding how citizens move through their city and what the various ecosystem players need to provide their services, and the design a coordinated, almost “acupuntural” response that allows all key parts of the system to work together seamlessly by providing lacking capacities, coordination layers and investment capacity avoiding unnecessary competition, reducing friction and solving market failures.

In this way, all the players in the ecosystem – not just the users – could leverage on shared enabling capabilities, such as shared payment systems, integrated route planning, quality standards, and could even participate in coordinated governance structures and investment funds even co-investing and reaping benefits of various kinds, ranging from financial to other forms of regenerative impacts where they have interest and skin in the game.

This shift towards situated regional, local, or national mixed “portfolio” institutions can be based on what we often call—when we work with companies—”reverse Conway thinking”: instead of letting organizational structures dictate how services are delivered, we design organizational architectures that support the outcomes we want to achieve.

The Portfolio Map Canvas: Seeing the Whole System

Our Portfolio Map Canvas has emerged from extensive research and practical application with organizations ranging from healthcare to mobility, system integration, and innovation agencies. It provides a strategic visualization that aligns everything to customer needs: re-budled organizational capabilities and go-to-market channels across an entire organizational ecosystem.

More importantly, it highlights the gaps and opportunities for reteaming, investments, or policy intervention that would be impossible to define when single units or functions plan in isolation.

The canvas (and generally the approach we follow) consists of mapping the complete ecosystem of users and providers, including all their needs, and then identifying all the different types of value that can be created to serve that complex system effectively in the form of products and services. Then it maps the current ecosystem of capabilities that exist to support such as product/service vision: in a company, it may be the set of functions, product units or support structures; while in a public sector context, it may map both public agencies, social economy players and private business players involved.

When used with companies, the map reveals overlaps that create inefficiencies, for example, after M&As, and gaps that leave needs unmet. Furthermore, it helps us identify core dependencies that often slow innovation and hinder autonomy. It prompts us to determine how organizational rearrangements can be defined to solve them or how investments should be allocated to build capabilities lacking to deliver a more capable set of solutions.

Our early research shows that optimizing public services ecosystems doesn’t always require building new capabilities. Sometimes, it requires making orchestration services available or improving the capacity of the specifics on which everything depends.

Consider how this approach could transform regional healthcare systems: Health authorities could discover that their most significant opportunity lies in creating infrastructures for “care orchestration”—that coordinate between care providers—and, at the same time, seeding essential complementary specialist services, community health programs, and social services to close the circle. Coordination capabilities that don’t belong naturally to any existing organization are often essential for the system to work effectively, but rarely get built.

The successful story of Buurtzorg, which revolutionized home healthcare in the Netherlands by creating ecosystem-wide coordination software tools and enabling coaching services that delivered incredible patient outcomes despite coming from the private sector, can inspire public players.

The 3EO Framework: Organizing for Ecosystem Impact

Boundaryless’ 3EO (Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Enabling Organization) topology framework provides a practical approach to implementing ecosystem-based organizational endeavors that can deliver systemic outcomes.

Within this topology, entrepreneurial micro-enterprises can focus on direct value creation for specific customer segments. These might be specialized teams within larger organizations or independent entities responsible for particular services or customer groups. They operate with clear accountability for outcomes and the autonomy to innovate and deliver value.

Enabling platforms, on the other hand, provide shared capabilities that micro-enterprises can leverage. These include technical infrastructure, regulatory compliance expertise, data analytics capabilities, or standardized quality assurance processes. By sharing these functions across the ecosystem, individual service providers can focus on their unique value-added capabilities while benefiting from economies of scale and consistency in foundational capabilities.

Ecosystem leadership functions can then coordinate across the entire network, setting standards, facilitating collaboration, resolving conflicts, and ensuring that the ecosystem works toward strategic shared outcomes. In companies, these functions normally provide investment capacity or facilitate participative strategic processes and would naturally fit the role of public sector institutions. However, they can also be shared and self-organized across multiple private stakeholders through innovative governance structures, where public sector players can play more of an “enabling”, catalyzing, and facilitating role.

The power of this framework becomes clear when we examine successful implementations like Barcelona’s approach to urban innovation. Rather than running separate programs through different departments, the city created an integrated ecosystem where citizens’ needs are addressed through coordinated networks that span municipal services, local businesses, community organizations, and research institutions. Their “living labs” model demonstrates how ecosystem thinking can generate solutions that exceed what any organization could achieve working alone.

Similarly, Estonia’s digital government transformation illustrates how ecosystem orchestration can work nationally. Instead of digitizing individual services separately, Estonia created a shared digital infrastructure that allows different government functions to interoperate seamlessly while maintaining security and citizen privacy. Citizens can access dozens of other services through integrated digital interfaces, without understanding the organizational complexity.

Building Public Digital Infrastructure for Ecosystem Collaboration

One of the most critical insights from our work has been recognizing that effective ecosystem collaboration requires shared infrastructure, not just technical infrastructure, but shared semantics and governance infrastructures to work together effectively.

India’s pioneering work with digital public infrastructure provides a compelling model. Their Unified Payments Interface (UPI) created a shared protocol that allowed thousands of different service providers to interoperate seamlessly. Similarly, their Open Network for Digital Commerce is now making a shared interface that allows small merchants to participate in digital commerce without being locked into any single platform.

This approach has direct applications for public service ecosystems. Imagine if different health providers could seamlessly share patient data while maintaining privacy protections, if educational institutions could coordinate student support services across organizational boundaries, or if social services could smoothly hand off cases as people’s needs change over time.

Creating this kind of infrastructure requires “ontological commons”—shared ways of describing services, capabilities, outcomes, and quality standards that become foundational public goods. These commons reduce the transaction costs of collaboration and make it possible for new types of partnerships to emerge organically.

Beyond Profit and Loss: Measuring Ecosystem Value

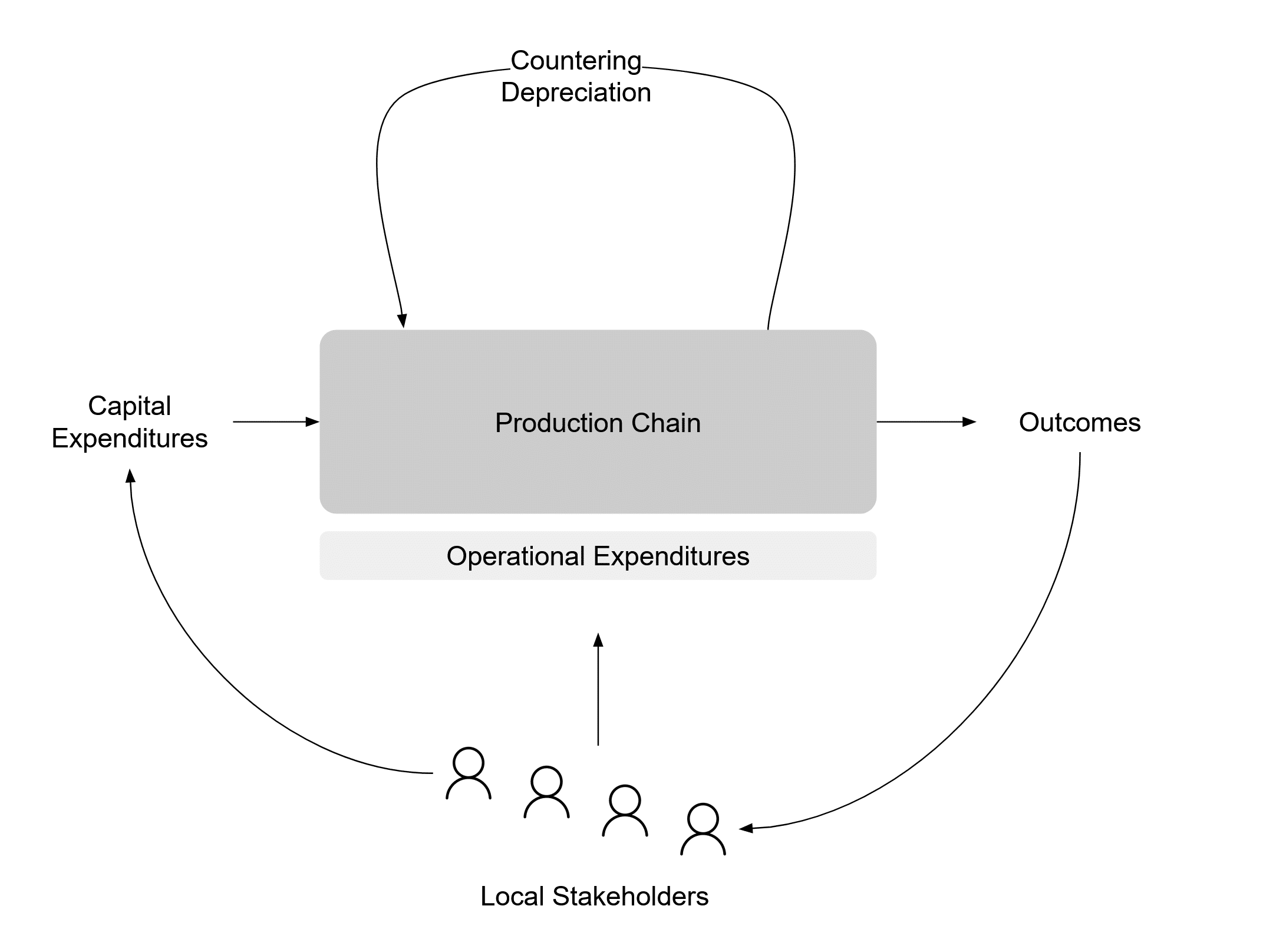

One of the most significant shifts in ecosystem thinking involves how we measure and drive success. Traditionally, in private organizations, the key metrics have been financial performance: Profit and loss is often used as the core “forcing function” in large organizations with extensive product portfolios, while in scaleups, we usually adopt proxies such as OKRs that allow for a more strategically coherent execution that aligns more closely with a specific product roadmap.

In Public Ecosystem metrics, we must capture how well the network serves shared impact outcomes.

This has led us to explore “regenerative metrics”—ways of measuring and incentivizing value creation that go beyond traditional economic indicators. These might include community resilience, environmental sustainability, social cohesion, or capacity-building measures. The challenge is not just in measurement but in creating incentive structures that align the individual node’s interests with the ecosystem-wide outcomes.

Some of the most innovative work in this area involves creating new kinds of credits or tokens representing different value creation types. As carbon credits have developed markets for environmental benefits, social impact credits could create economic incentives for organizations to contribute to community outcomes. Biodiversity credits reward ecosystem restoration, education credits incentivize skill development, and inclusion credits support efforts to reduce inequality.

These mechanisms work best when they’re designed to be used in the governance structures of ecosystem initiatives from the beginning. They create what economists call “alignment between private incentives and social benefits,”—making it profitable for organizations to do things that benefit the broader ecosystem.

The problem with credits, though, is that they are often used to swap someone’s positive for someone else’s negative externalities. Carbon credits—especially those now traded worldwide as “currency”—usually only represent a palliative solution while undoubtedly driving positive behaviors. Furthermore, the KPIs measuring impacts are often unclear, leading to a lack of trust. The focus is often on parts, such as soil, rather than on really systemic outcomes, which has prompted a general discussion about the validity of such measurements.

In this context, at Boundaryless we’ve been preaching the creation of closed-loop systems where more than looking for the financialization of positive outcomes, local, contextual positive impacts can be traded in the vicinity of where they’re created (as local currencies for example) or can be rewarded by investors impacted by short-loop first, or second order effects. Imagine, for instance, that part of local taxation income could be translated into local impact tokens that could be distributed (in various ways) to citizens, to be used to purchase regenerative services locally. This would directly translate taxation into regenerative regional impacts by closing a value loop.

The challenge, as often, is to create the inclusive institutions tasked with facilitating a local conversation around value, helping communities think strategically about what they want to achieve, and hosting such participative, strategic discussions.

Practical Implementation: Where to Start

For institutions interested in exploring ecosystem approaches, the most effective starting point is usually mapping current user journeys across institutional boundaries. This will reveal the pain points an ecosystemic approach can address and the existing relationships that aren’t being leveraged effectively.

The Portfolio Map Canvas provides a structured way to facilitate these conversations across multiple stakeholders, making the coordinating functions that need to exist but don’t currently belong to anyone in particular, visible.

Successful implementations often start with pilot projects that demonstrate the value of ecosystem thinking before attempting larger transformations. For instance, a housing authority might begin by coordinating more effectively with employment services and healthcare providers for a specific neighborhood before expanding to city-wide initiatives. A university might integrate student support services across departments before engaging with external community organizations.

The key is to create early wins that build trust and demonstrate the practical benefits of ecosystem thinking while investing in the infrastructure and capabilities supporting broader transformation over time.

An Invitation to Collaborate

As we prepare for our upcoming INCOSE webinar with Lucia Hernández, we’re particularly interested in connecting with institutions (or private-public networks) grappling with challenges that exceed their capacity to solve. The Portfolio Map Canvas and 3EO Framework are open-source tools we’ve developed to support this collaboration.

We’re looking for partners ready to experiment with ecosystem approaches, whether coordinating across government agencies, building new public-private partnerships, or creating innovative governance structures for multi-stakeholder initiatives.

The challenges we face—climate resilience to economic inequality, technological disruption to demographic change—require responses that match their scale and complexity. Regardless of its resources or mandate, no single organization can solve these challenges alone. But by learning to orchestrate ecosystems effectively, we can create responses leveraging our communities’ full capabilities and resources.

The tools and frameworks exist, and successful examples are emerging worldwide. We need more leaders willing to experiment with new forms of collaboration and governance and, most importantly, open to hosting a discussion on value and the role they need to develop in this new reality.

We invite you to join us in exploring what becomes possible when we match the scale of our collaboration to the scale of our challenges.

Simone Cicero