From Bureaucracy to Market: How Chargebacks Can Transform Your Organization Without Breaking It

This article explores how chargeback models can transform organizations from bureaucratic to market-based, user-centric structures. Drawing inspiration from Haier’s Rendanheyi model and the impact of AI on transaction costs, it argues for a decisive shift towards empowering entrepreneurial units. The piece highlights how this approach fosters greater accountability and optimizes for user value by moving away from centralized budgeting.

Simone Cicero

As we’ve explained recently in “How AI Transforms the Logic of Value Creation in Markets – and Organizations“, the emergence of AI as a powerful coordination technology brutally reduces transaction costs and is going to accelerate this trend further:

“The fundamental economic promise of AI agents lies in their ability to dramatically reduce transaction costs—the expenses associated with using markets to coordinate economic activity.”

[From “The Coasean Singularity? Demand, Supply, and Market Design with AI Agents”]

Therefore, organizations should move decisively into a market-based, user-funded, zero-distance organizational model. Chargeback models – where organizational units exchange services and products for money also interally and not just externally – can help allocate costs and value fairly in organizations.

These approaches aren’t new, but the 3EO framework (inspired by Rendanheyi) can help apply them without generating classic drawbacks:internal competition that undermines collaboration, short-term thinking, fragmentation of the customer experience, and loss of control over aggregate performance indicators like group-level EBITDA.

From Bureaucracy to Zero Distance From The User

A few years ago, I remember we interviewed John Bunch about the Zappos experience in moving from top-down budgeting to market-based dynamics. He explained:

“Every team is like a small business,” and you can only pursue your mission if “someone is willing to pay you internally or externally for that service.”

Haier adopted a similar approach when introducing its Rendanheyi model in 2012: it transformed thousands of employees into micro-entrepreneurs. They eliminated 10,000+ middle-management positions, pushing P&L responsibility to self-managed teams that had to find paying customers or risk ceasing to exist. The legend was born.

Not everyone, though, can be so upfront about the change and say, “Starting tomorrow, if you don’t have an internal or external customer, you cease to exist.”

The goal of such a transformation isn’t to adopt “chargebacks” per se, but to achieve high accountability in the organization.

When revenue and planning are centralized, everyone optimizes for the plan and to protectthe budget. When accountability is at the edge of each unit, everyone optimizes for the user. To get there, chargebacks must become a value-splitting mechanism rather than an internal tax. If we do it right, we make three things true at once:

- everyone becomes user-paid (directly or via clear internal contracts);

- The experience remains coherent end-to-end.

- aggregate performance improves under explicit margin and brand constraints, not micromanagement.

The Concepts You Need

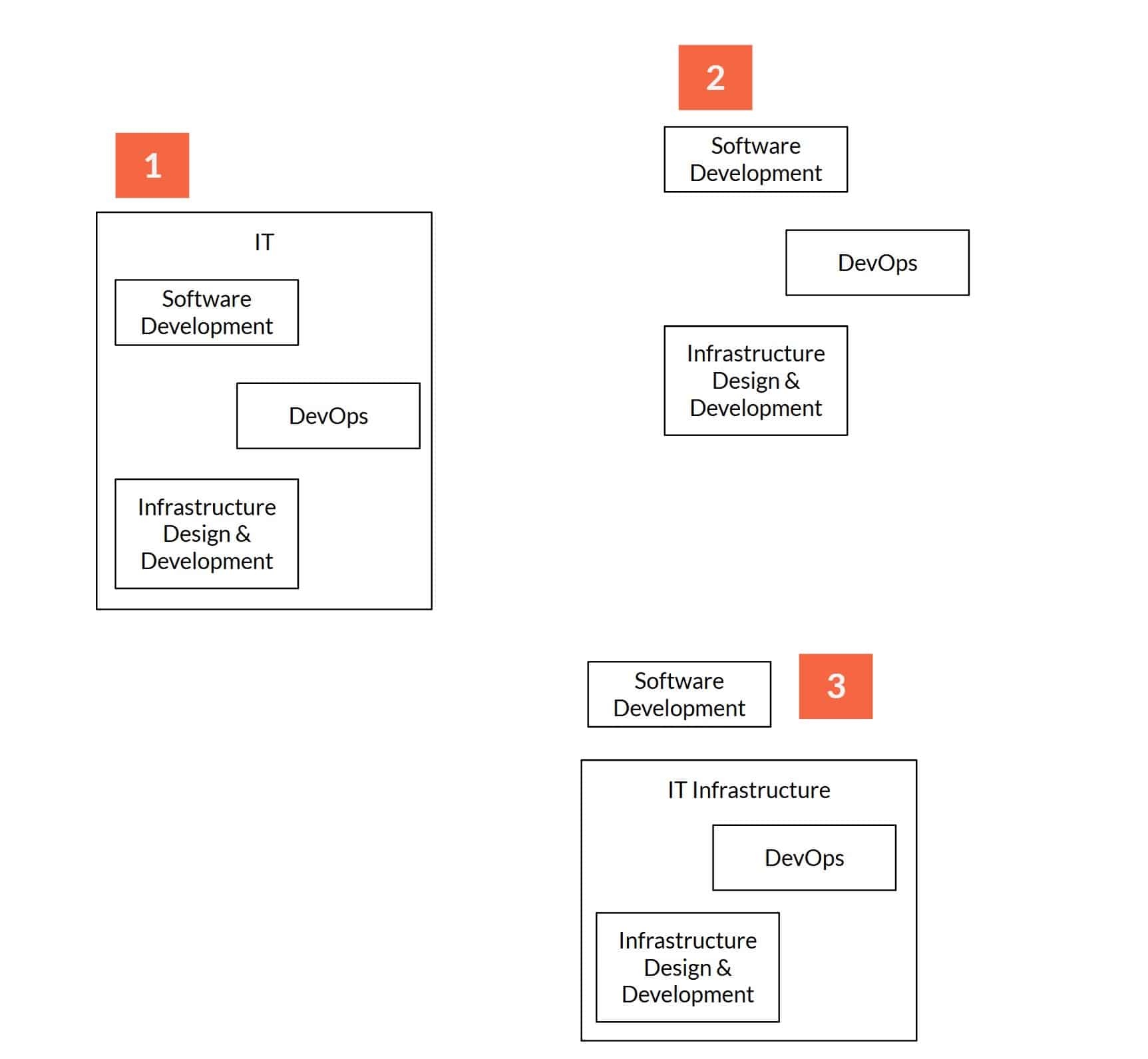

A good starting point for organizations seeking high accountability is to first unbundle and re-bundle. Unbundling means first separating large, existing functional units into smaller ones to make independent sub-units and teams more visible. For example, you could unbundle a large IT development unit into Software Development, DevOps, and Infrastructure Design and Development: both provide quite independent services that can be sold together to customers or separately.

When unbundling the organization into smaller units, we should consider where independence and contestability exist: can alternative suppliers (inside and outside) realistically provide that service or capability? Is such a capability independently viable?

In Rendanheyi/3EO and similar approaches, we typically have three unit types. Different companies name them differently, but the roles are invariant and map 1:1 to the three domain types in Domain-Driven Design.

- User Micro-Enterprises (UMEs) ⇄ Core Domains. Edge units that own the customer, outcomes, and profit and loss.

- Node Micro-Enterprises ⇄ Supporting Domains. Specialist capability suppliers forvarious solutions and experiences.

- Shared Service Platforms (SSPs) ⇄ Generic Domains. Enablers like HR, Finance, and IT with transparent transfer pricing.

To demonstrate that these types are invariant, let’s take Bayer’s DSO. Language lands in the same place (see Michael Lurie’s update): Customer & Product Businesses behave like UserMEs/Core Domains, Capability BusinessesresembleNode MEs/Supporting Domains, and Enabling BusinessesreflectSSPs/Generic Domains.

After unbundling,it’s always essential to consider re-bundling. If dependencies are tight between newly identified nodes, the user experience would suffer from separation. It’s then worth keeping them together in a single P&L container. Your goal isn’t extreme atomization, but rather to expose units that can autonomously create value —reasonably independent units. If we see that the DevOps team and the Infrastructure Design and Development team have continuous handoffs, use the same toolchain, make decisions together, and often serve the same customer, then we can assume they are part of the same team. It may make sense to “rebundle” them. Below you can see how the three steps go together.

How The Money Flows In The Game: Experience and Solution Contracts

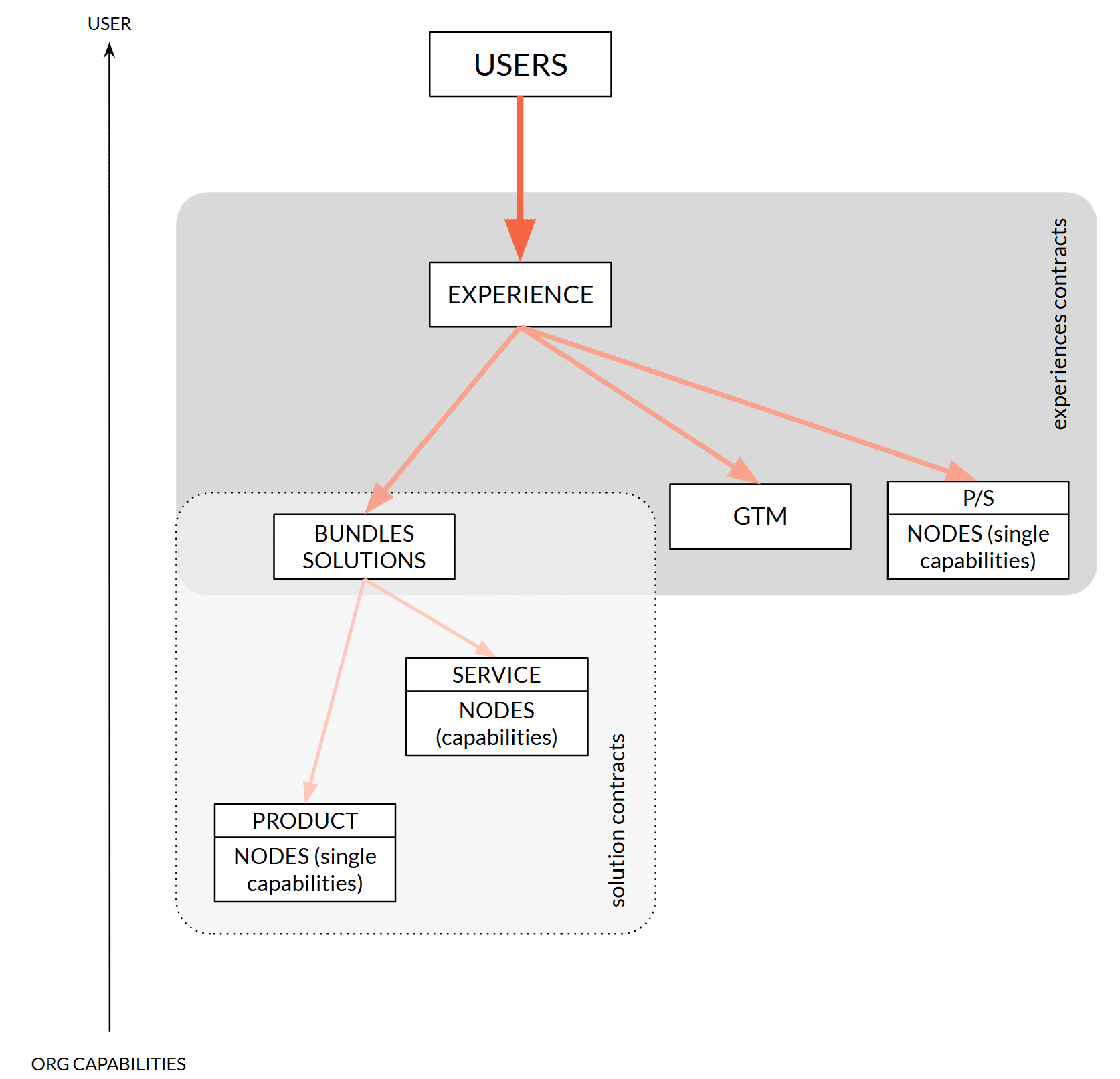

Now, let’s shift to how money moves. Revenue typically enters an organization through some customer “experiences”. An experience is a go-to-market entry point (a storefront, a project offer, a bundled subscription, a tender).

Solutions, on the other hand, are replicable products and services composed through the collaboration of internal capability providers (teams, platforms).

Both experiences and solutions can be viewed as contracts that coordinate commitments to a specific promise and split revenues or profits. The split needs to be explicit and negotiable: who contributes what, who earns what.

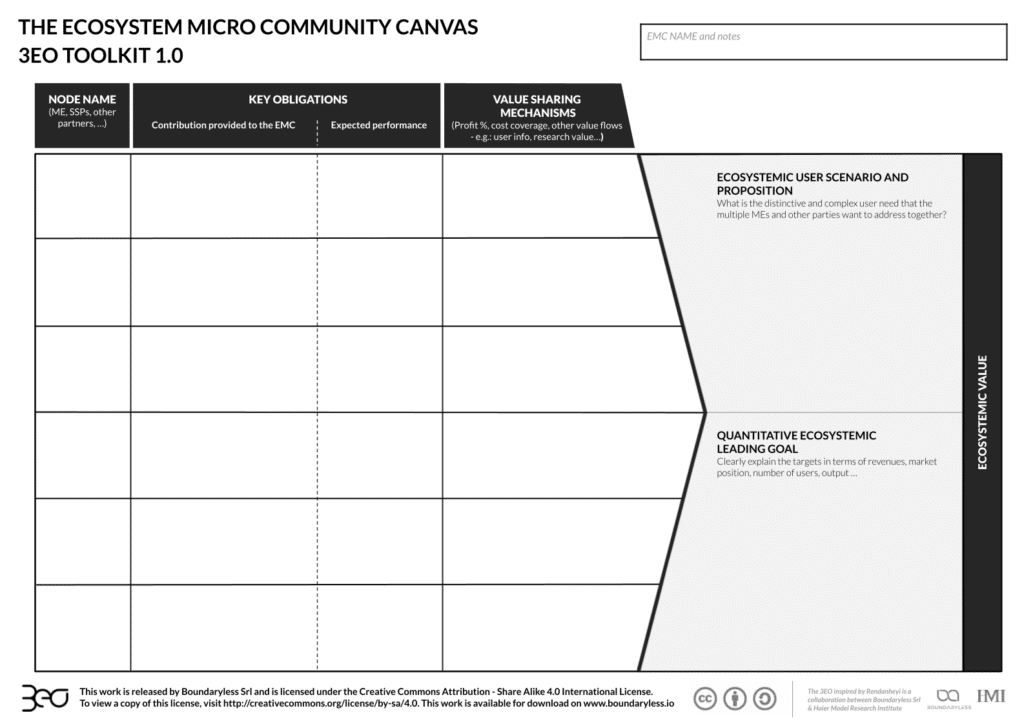

To address this tension, the 3EO Framework, inspired by Rendanheyi, features the Ecosystem Micro-Community Contracts (EMC Contracts). EMC contracts are contract types pioneered by Haier in the late 2010s, invented to define how value is created, delivered, and shared among participants in a collaboration, establishing clear rules for revenue distribution and performance accountability across units.

An EMC Solution contract can be used to cover the obligations of the nodes involved in producing a replicable element of the product or service portfolio, ensuring a realizable product or service. On the other hand an Experience EMC Contract should support a Go-To-Market configuration that allows the solution (or multiple underlying solutions) to be composed and delivered to the customer. Solutions and Experience contracts can be considered just another type of node, used to split revenues based on certain obligations of the participating nodes.

With such contracts in place, nodes (teams/units) can operate much faster: well-defined revenue-splitting contracts, where prices emerge from negotiations over value rather than an internal cost-plus approach, are the best way to make chargebacks value-based rather than a simple tax. All with a shared contract grammar.

In this way, the org becomes a network that routes value rather than a maze requiring continuous approvals.

Maintaining these two levels allows solutions to have an internal focus on arranging the internal capabilities into a catalog of long-lived services and products, while experiences can adapt to the tune of a particular customer segment, locality, or period, and can help compose solutions into more complex customer “scenarios” also involving third parties and partners. For example, an experience could involve a third-party system integrator providing integration services, while a parking operation company offers both a software platform for parking automation and a catalog of certified hardware, such as cameras or automated parking barriers.

Example: Solution and Experience Contracts

To give a more tangible idea, let’s imagine a fictional digital health company,Healthransform, that offers imaging hardware and SaaS for ancillary functions like digital Pathology.

Let’s introduce the Intelligent Imagine Solution. It’s a ready-to-use imaging product that bundles the customer-installed hardware, digital pathology software for real-time AI image analysis, software to connect and monitor the hardware, installation, ongoing maintenance, and basic compliance/quality. For the customer—typically a hospital or lab—it behaves like a single reliable system: it’s installed, connected, and kept functioning. Internally, it’s a simple Solution EMC, a contract between a units that designs the hardware, the one that Manufactures it, The Software Development Unit, and the installation & maintenance unit: it states what all units promise (availability, response, preventive checks), who is accountable for what, how its measured, and pricing for anyone selling it to the customer – along with resource redistribution. Because it’s standard and reusable, multiple offers can “plug it in” without reinventing scope or service levels.

This solution is also sold as part of a new Experience (EMC) Equipment-as-a-Service (Renting) model. Two units participate: Sales, which identifies and cultivates demand, maintains customer relationships, and owns the sales process; and Finance, which handles contracting, credit checks, funding, and designing end-of-term options. The third component is the contract representing the solution, typically held by the “leading unit,” like the hardware design team. The negotiation stipulates that once a sale is completed, the sales team receives an upfront fee as a quota, while the finance team provides the capital to cover the hardware’s manufacturing costs. Activation and monthly payments are divided, with a portion routed to the finance team as interest and fees, and the rest allocated to the solution contract, which distributes funds to the underlying units.

Customers see clear value: a quick go-live followed by a predictable monthly fee that includes connected hardware, software, and maintenance, offering a single support contact. The Experience is designed as a collaborative effort.

Enabling Constraints That Keep The Game Healthy: Taxonomies and VAMS (Investing and Operating Contracts)

Once units can negotiate value to improve their performance through customer accountability, you’ve created a game. To make it good —avoiding internal price gouging, broken customer journeys, and the race to local optima where one unit risks the whole—you need to give nodes not just the tools, such as contracts, but also constraints, guardrails, charters for the nodes to operate within, the expression of being “part of” something bigger (the org) versus playing the game alone in the market.

A soft taxonomy

Alongside organizational structure, the organization needs to understand its customers, reference ecosystems, and product relationships. Some organizations are better seen as a “portfolio” of unrelated products, while others are more like “platforms” of composable options (see this article for reference). Especially in the former case, agreeing on a lightweight taxonomy of products, capabilities, and services (and a shared way to describe customer needs) can be crucial for facilitating bundling. A composability map helps teams discover each other, compose solutions faster, and avoid reinventing parts of their solutions. See some of our prior writings on the topic here: 1,2,3.

P&L clarity, including shared-services “taxes.”

Revenues from EMC contracts constitute the node “inflows”. Salaries, input costs, and payments for shared services typically make up the negative side of the P&L. In our experience, companies use several methods to account for Shared Services (usually provided by Shared Services Platforms). These services — which are general and used by everybody — don’t provide a competitive advantage. SSPs rarely negotiate directly with micro-enterprise counterparts. It’s usually more efficient to apply a capacity levy based on headcount for HR services, or other indicators that serve as reasonable proxies for the service (like office space as a proxy for facility management). Sometimes, Shared Services are funded through a revenue tax, with the downside that positive behaviors, such as headcount optimization, are not incentivized. The important thing is to make the rules explicit and benchmarkable—and establish clear guidelines for cases when SSP services do not meet specific expectations and MEs want to source alternative services from the market.

The picture is simple: Revenue comes in → flows into Experience & Solution Contracts (with Split Rules) → and eventually flows into Nodes.

Experiences collect customer money, apply the split rules (percentages, thresholds, waterfalls), and route value to solutions that fulfill them or other capability nodes (like GTM). Solutions then route to contributing nodes. Shared services take their fee per published transfer prices or levies directly from the nodes.

A VAM-style charter from the parent node.

Finally, to stabilize the system, the “parent” organization (industry platform or holding) must set the enabling guardrails: access to the brand and sales channels, compliance boundaries, alignment cadences, andoperating margin targets need extensive definition and negotiation in a basic operational agreement on top of which Value Adjustment Mechanism contracts are negotiated.

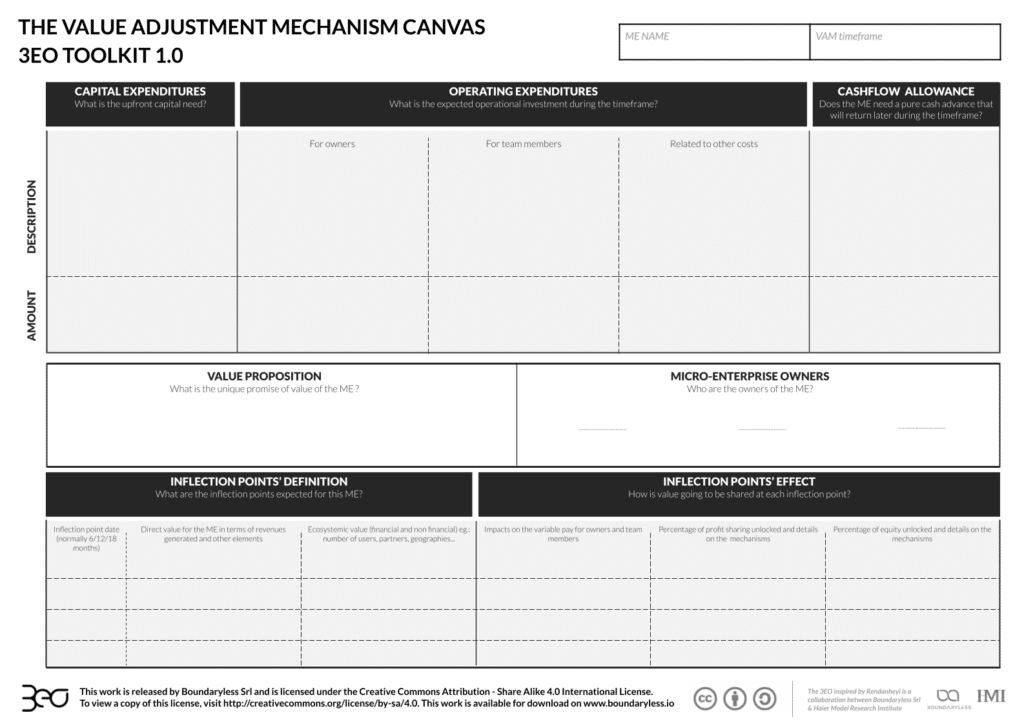

A VAM is a contract that allows entrepreneurial employees to negotiate the upside of their work in taking over or creating a unit with the mothership. Every unit, in addition to relying on contracts to negotiate revenue or value splits, must do everything that ventures do: talk to users, hire, innovate, build new capabilities, and enter the market. Such units have to request capex and opex and set objectives.

In our experience, a VAM contract negotiation centers on requesting investments, clarifying expected OPEX, and seeking financial support, like cash flow allowances and solutions for managing stock creation in hardware-related endeavors. A key negotiation point is the unit’soperating margins.

The operating margin target becomes the stance units use when negotiating contracts. If I know I need a 30% operating margin by year-end, I’ll negotiate contracts accordingly. During negotiations, I’ll balance improving my operating margin with staying within the bandwidth of value extraction that then cascades into an acceptable end-user price. Units must manage this tension, typically created by setting rules in the VAM that allow profit retention if minimum operating margin objectives are met. This usually means the unit retains profits exceeding the VAM targets, provided they exceed a minimum and a certain operating margin percentage.

To prevent the organization from becoming hostage to a single unit, it’s wise to either duplicate the units that provide specific services internally or minimize constraints on sourcing alternative customers and suppliers, both within and outside the organization.

Example: Transforming the Software Development Unit into a Micro-Enterprise (Healthransform)Scenario: The leader of Healthransform’s Software Development Unit wants to turn it into a Micro-Enterprise (ME) via a VAM agreement.

The new ME will launch an ambitious project: an App Marketplacefor third parties to build and distribute apps on Healthransform’s connected imaging hardware.

The ME owners want to negotiate a few essential aspects:

- Revenue rights. The ME retains 85% of Marketplace revenues (developer fees, app listing fees, in-app revenue share); 15% goes to the Parent as brand/IP royalty for the first three years. All other revenues from integration projects continue to be 100% retained by the ME.

- Operating discipline. The ME will target a long-term 65% Operating Margin after paying salaries, infrastructure costs, and all other operating costs with transparent pricing for shared services (benchmarked; contestable if >10% over external equivalents). For the first two years, the Operating Margin target will be dropped to 50%.

- Level-up trigger. If the ME onboards 20 certified third-party apps, and achieves +25% Marketplace GMV for two consecutive quarters, the royalty drops to 10% (i.e., 90% retention); pricing levers (developer tiers, listing fees) become ME-controlled within Parent guardrails.

- Investment & gates. The Parent will allocate €1.2M CAPEX over 24 months, released in three tranches tied to: MVP (developer portal + billing), Pilot (first external developer cohort live), GA (compliance review and moderation workflow). Missing a gate by >90 days triggers VAM re-discussion.

- Spin-out option. If the Marketplace generates €4M incremental revenues above the starting floor while meeting quality/compliance targets, the ME is incorporated as a NewCo; ME owners receive 20% of NewCo equity.

A More Thoughtful Approach Than “find a customer or we’ll fire you”

Such a shift toward a user-paid organization can fracture culture, strategy, and customer experiences if it is not grounded in the correct principles and staged appropriately.

The provided concepts and elements (MEs, P&L, Solution and Experience EMC Contracts, VAMs) and the Portfolio Map Canvas can aid in-depth analysis – visualizing domain continuity among teams and units and suggesting how to unbundle and rebundle into independent units. The Canvas can help identify where contracts should be adopted to create revenue splits, corresponding with user-facing experiences that combine go-to-market capabilities and solutions.

We usually suggest a phased approach, moving in steps.

Phase 1 (Virtual P&L)

The first phase is about identifying nodes, creating initial virtual P&Ls, and enabling showback. There are many ways to do this: start with an overview from someone who can govern the finances, aided by existing unit identification, solutions, and experiences. Then, start a competitive game where teams negotiate the fine-tuning of their value share, even if they’re still not accountable to P&L.

Phase 2 (Live contracts)

In phase two, we typically construct and publish the experience and solution catalogs, negotiate the agreements and splits with the holding’s support, and begin paying for shared services in accordance with the agreed-upon rules.

Phase 3 (VAM and upsides)

In phase three, MEs can negotiate VAMs that exchange autonomy for targets and transparency, often with meaningful upside. Units step into entrepreneurial mode—within a coherent, benchmarked internal market. This phase is gradual, with new MEs emerging and old units transitioning. During this stage, units can engage in more contracting to create new solutions and experiences. This is when you’ll start to feel the need for the underlying technology. At Boundaryless, we’re developing a shared, open standard for implementation and our own SaaS application for easy integration with your ERP system. Reach out if you’re interested in piloting.

Some firms will go radical (think Haier’s elimination of middle management). The phased route achieves similar outcomes with less shock and better customer alignment. The result is a gentle transition onto an internal market that pays for value creation while preserving the experience.

What Architects and Leaders Should Watch For

Four design levers keep this approach efficient:

- Contestability. Avoid 1:1 internal monopolies. If a service is externally available, keep a credible make/buy option, publish benchmarks, and require exit clauses.

- Avoid one-on-one dependencies.Avoid two nodes with separate P&Ls but highly dependent capabilities. If neither makes sense on its own, group them.

- Avoid constraints on captive choices. Avoid constraining one node’s options to serve or be served only by a specific internal node. Openness keeps the system on track and prevents debt.

- Credible Operating Margin targets. Set credible VAM-set operating margin constraints; it would be irrational for any node to “go rogue” on price—overpricing makes bundles uncompetitive and destroys their long-term returns.

Getting Started

This article offers a clear lexicon and a credible approach to tackle this without major disruptions: understand, unbundle, and rebundle the units, map the entry-point experiences, and draft contracts; outline the solution catalog and revenue splits; establish a soft taxonomy; open virtual P&Ls; publish contract templates; and draft initial VAM charters. Run pilots and learn from the data. This is the only credible way to transform a bureaucratic monolith into a network where value flows naturally.