Horizontals, Verticals, and the ILC Model: a Recurring Pattern for Innovation in Platform-Portfolio-Based B2B Companies

In our most recent engagements on organizational development and streategy perspective – what we call strategic alignment – we’re seeing a recurring structure with clients who have a portfolio component with multiple services and a platform cohesion component, which deserves attention.

Simone Cicero

Recently, we’ve written about how successful organizations essentially balance a portfolio, diversification strategy with a platform one that ensures cohesion and a strategic capability to leverage cross-product synergies, targeting a complex ecosystem of customers.

This article examines a recurring positive organizational pattern that we’ve identified in companies that successfully balance portfolio diversification with platform cohesion. Through our work with multiple clients, we’ve observed how leading organizations structure their offerings around horizontal platforms and vertical solutions, while implementing continuous innovation cycles that capture value from their ecosystems.

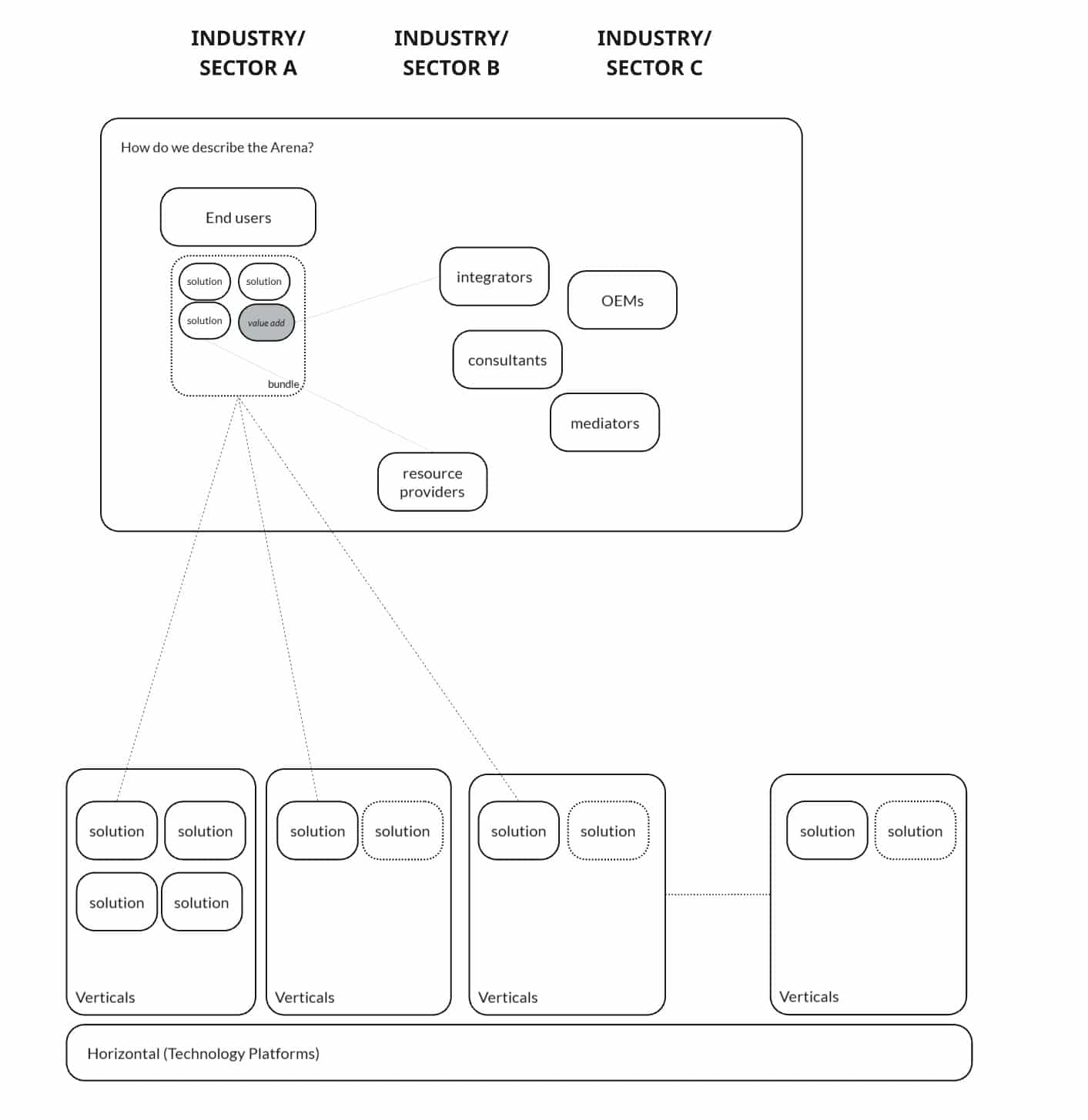

The Horizontal-Vertical Taxonomy

As we explained previously on the blog, an essential piece of running a cohesive strategy and a composible portfolio lies with having an intentional, well-understood product taxonomy: the way offerings are not only organized but also combined.

Practically, in the B2B situations we observe, most of the time, there’s a distinctly horizontal offering component. These horizontals are often technology platforms that can be of various types:

- high-level design of modular hardware components and systems

- advanced technology and research elements,

- firmware, operating systems that provide the foundation for a whole series of other developments

- design system components for user interfaces

- enabling data structures and software foundations.

These enabling technology platforms need long-term maintainability, and they typically make choices that don’t respond to short-term needs but rather to prevalent needs in the organization’s reference ecosystem, even across industries. For example, in a company that builds aerospace technology, these basic “platforms” may focus on avionics, software systems, sensor integration, or propulsion architectures. Similarly, in healthcare technology companies, horizontal platforms might encompass lab technology infrastructure, diagnostic algorithms, and patient portal technology. All modules serve as foundational elements across multiple product lines.

What distinguishes these horizontal platforms is their deliberate abstraction from specific use cases. They’re designed to be flexible enough to support diverse applications while maintaining consistency and reliability. This abstraction typically requires long cycles, significant upfront investment in architecture and design, and relatively low fluctuations to respond to specific customer needs. Still, it pays dividends through reduced complexity and increased manageability, and baseline performance across the organization’s entire portfolio.

On top of these horizontals are the verticals: sometimes formalized organizationally as micro-enterprises or product units, product areas, these units cater to more specific customer needs. They perform productization activities, seeking to respond to the experiences and typical needs of a more specific market segment compared to horizontal solutions, approaching this through the creation of specific solutions to customer problems and needs.

While platforms aim to create enabling capabilities, there’s often collaboration between different verticals to create bundles – integrations that respond to specific customer needs. Verticals indeed have often remarkable system integration capabilities, and learn from clipping pieces together in the particular context of the customer, with various levels of system integration required, depending on the context.

Different Levels of Integration

This customer-facing bundling and integration occur at varying levels of depth. For example, HubSpot has separate products, and its bundle integration primarily involves activating different self-service packages on the platform. A company doing more complex and niche services, instead, goes through a heavier enterprise sales process to create a bundle, with system integration work.

The activity of combining products and services from different verticals is often where emerging customer needs are addressed. When we have a more mature platform, where third-party solutions also exist, that’s precisely where future customer needs are identified and value is created.

The Common Shape of the Reference Market

Examining the market landscape, especially in B2B, we typically see some recurrence in how markets are structured. Typically, organizations target core enterprise customers, which are reference customers from 2-3 different industries or types that share common elements in their business processes, typically resonating with the core modular offering components. For example, an industrial printing company may target both commercial printing operations and packaging manufacturers, as they share similar production workflows, quality requirements, and equipment needs. These core customers often represent 60-80% of revenue and drive the primary platform development roadmap.

Often, across or adjacent to the core targets, emerging segments represent future growth opportunities that require more significant platform evolution or entirely new vertical solutions to address effectively. Perhaps they share a subset of the needs of the core targets (e.g, operate factories, logistical needs, run subparts of key processes, research, …). They’re united by general needs rather than the industry they operate in.

Beyond the core, B2B ecosystems also feature a whole series of players acting as mediators, integrators, enablers, machine producers, OEMs, and eventually entities that produce resources which are consumable in industrial processes, or infrastructure players, such as commodities providers.

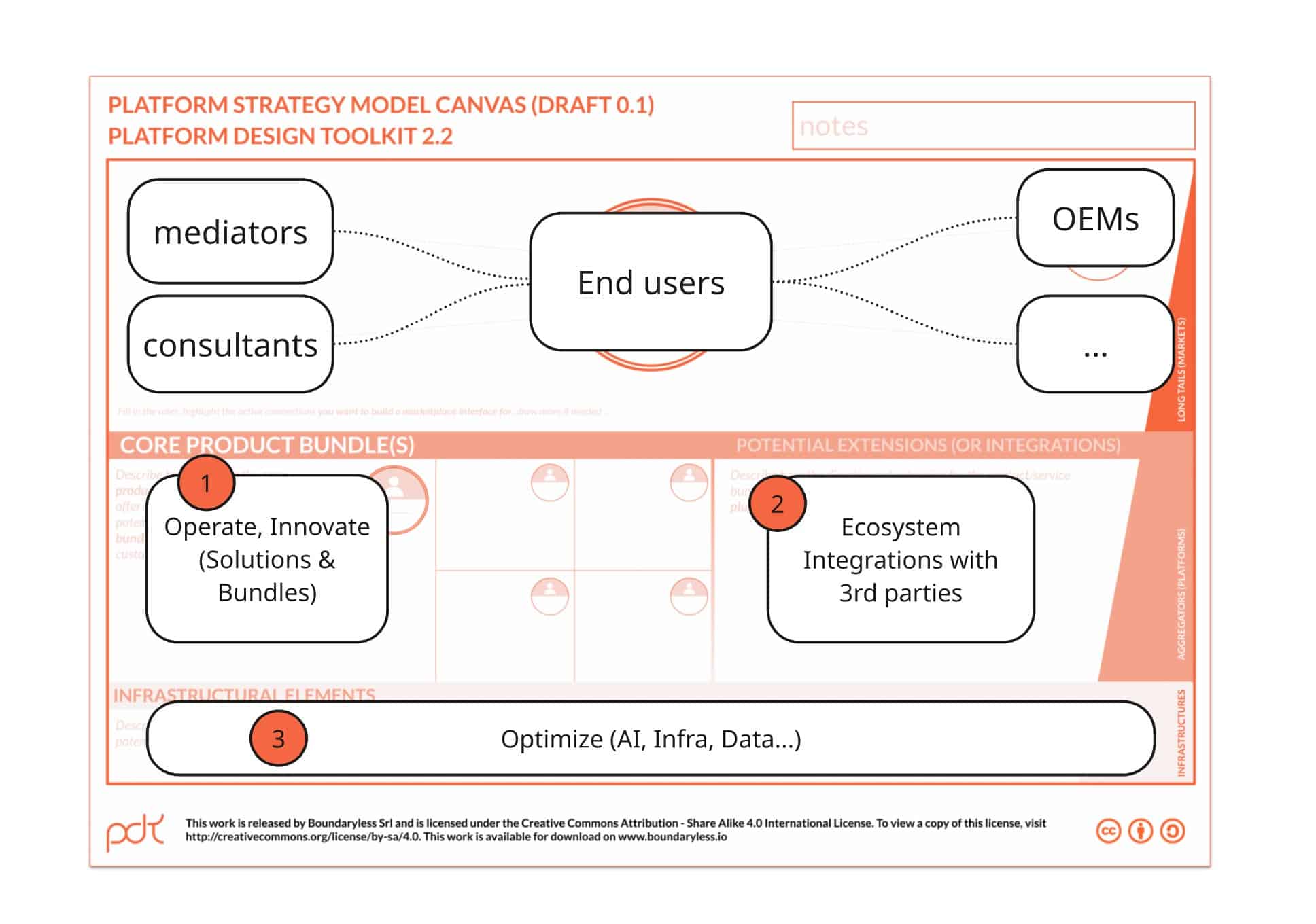

The Three Pillars of the Offering

As a conseguence the offering often develops along three macro directions:

- Operate/Innovate for core customers: this can involve an offering focused on the operational efficiency of the customer’s base workflows (operate) or an offering for deep innovation use cases (innovate). An e-commerce might be more operational, while a research tools producer may be more focused on enabling innovation-related use cases.

- Integrate: everything that extends and integrates core solutions – system integration, third-party extensions, partners – this part of the offering facilitates the adoption of key ancillary solutions to cover ancillary use cases: here’s where we typically see developer portals, partner programs….

- Optimize: optimization component, like infrastructure optimization, data, and, very often, lately, artificial intelligence-related adoption.

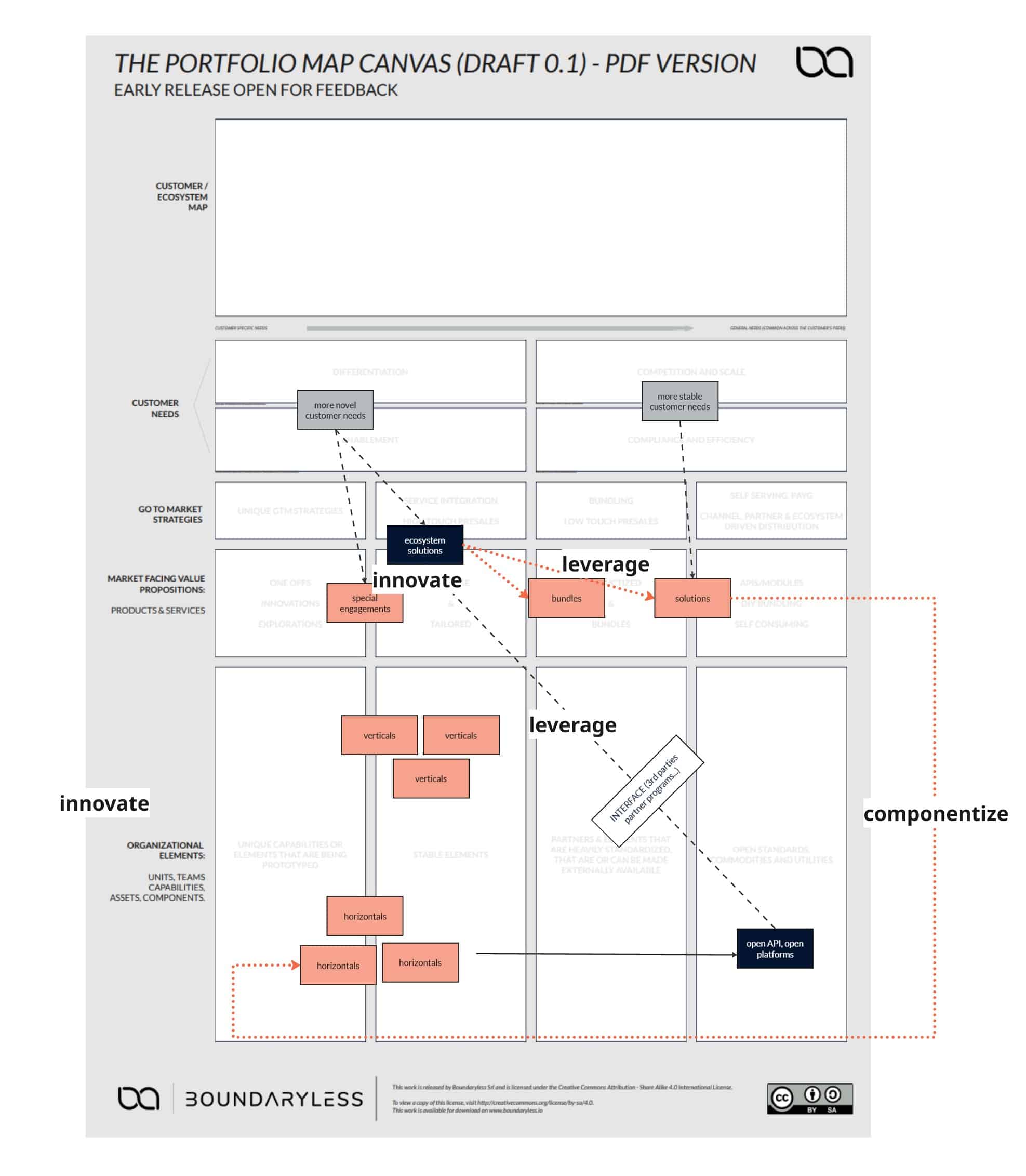

The ILC Model: Innovate, Leverage, Componentize

Now, if you look at your organization as a portfolio product set and platform strategy, why do you use a platform strategy? It mainly serves to maintain cohesion in products and services, guaranteeing the ability to leverage platform positioning.

The ultimate goal for a platform is to innovate continuously, create evolutionary tension with its ecosystem, and anticipate future needs, build them, and innovate continuously.

The ILC model, formalized by Simon Wardley, is a very clear and powerful explanation of how this mechanism can actually happen. According to the ILC model – a playbook that companies like Amazon have mastered – platforms evolve through three phases. First, they innovate by creating new capabilities that address emerging customer needs. Next, they Leverage these innovations across multiple products and customer segments to maximize value extraction. Finally, they Componentize mature capabilities into reusable, modularized platform services that both internal teams and external partners can consume.

This cycle enables platforms to continuously evolve while maintaining stability for existing users and creating opportunities for ecosystem expansion.

Therefore, according to the playbook, a good strategy for a platform-portfolio company in B2B is to:

- Modularize its offering as much as possible, starting from the platform-orizontal side, exposing it through clear interfaces to the whole ecosystem, and not only internal product verticals, and simplify access to innovative solutions, perhaps by standardizing them

- Allow the ecosystem to create higher-value solutions on top of the enabling systems.

- Capture what happens in the ecosystem and translate it into new products and services;

- Create a new round of innovation on top of newly modularized solutions

This is, for example, what Amazon did not only with AWS but also with Amazon Basics: they systematically identified top-performing third-party products in their marketplace (enabled by the platform services), analyzed the underlying customer needs, and then created their own streamlined versions. The key insight is that platforms must balance being both enabler and competitor – providing infrastructure for innovation while selectively internalizing proven concepts. This dual role creates healthy tension that drives continuous platform evolution and ensures the ecosystem remains dynamic rather than stagnant.

Organizational Implementation

From an organizational perspective, there must be a process that progressively transforms innovative use cases, produced by product units or partners, into more standardized components, then into organizational products, and finally into platforms—gradually bringing technological innovation to a componentization level, making it a module, an API on which to build more innovative things.

The mature implementation of this pattern would require platforms to modularize and open access to capabilities not only to internal companies but progressively to the entire ecosystem. Suppose I open my internal platforms to the ecosystem beyond my product areas. In that case, I’ll increase consumption of internal capabilities, capture more insights, and leverage external capacity – which is most important because we must always start from the assumption that the best is outside the organization, not inside.

The Challenge of Opening Up

Products, too, will need to modularize and open to third parties over time, because they’ll be the platforms of the future. Modularization for innovative products means making them accessible and open.

This is often not viewed favorably by companies, as they fear it will enable competitors. But this response doesn’t hold: if you don’t do this, you maintain your technology platforms in a genesis state in their entirety, effectively preventing them from evolving.

If you do this, you don’t put your capabilities under the challenge of external player demands; you don’t do platform-as-a-product work, which is crucial. This way, it’s easier to accumulate technical-organizational debt in internal enabling modular platforms, which don’t open to the outside, don’t capture evolution signals, and risk falling behind – becoming victims of competitors who instead open their ecosystems and embed themselves in customer use.