How Organizational Structures Evolve: From Functional to Matrix to Platform Models

In an era of organizational evolution, businesses are shifting from traditional structures to a platform organization model. This innovative approach promotes agility, fosters innovation, and enhances adaptability to fast-paced market changes. Leading examples highlight the transformative potential of platform organizations. However, this transition requires strong leadership, an accountability culture, and a supportive technological infrastructure.

Simone Cicero

Emanuele Quintarelli

Luca Ruggeri

From Functional to Matrix to Platform Organization

Even in the dynamic world of business, the evolution of organizational structures from functional to divisional, and to the matrix organization is now approaching a new era of change, that toward the so-called platform model.

This is not just a change — it’s a revolution. Markets are shifting in ways that demand radical optionality, and quick adaptation.

Thanks to cloud, AI, and other technologies, individuals and teams can grow fast, have huge impacts, and leverage. Transaction costs are plummeting thanks to communication technologies, protocols, and no-code, and organizations need to develop the capability to easily plug into external resources, quickly bundle their capabilities and products to produce innovations and connect with an ecosystem of external partners.

The question we face with customers is often about understanding how to transition smoothly and ensure that the people and the processes existing in the organizational setup can nicely evolve without total disruption from yet another organizational change, but rather evolve more iteratively.

Let’s delve deeper into this evolution by explaining how the key organization’s elements evolve.

The Platform Portfolio Deep Dive is a 1-Day Experience designed for executives and builders who want to learn how to manage an ecosystem of several products and services. Join us in Barcelona for the first Live Edition.

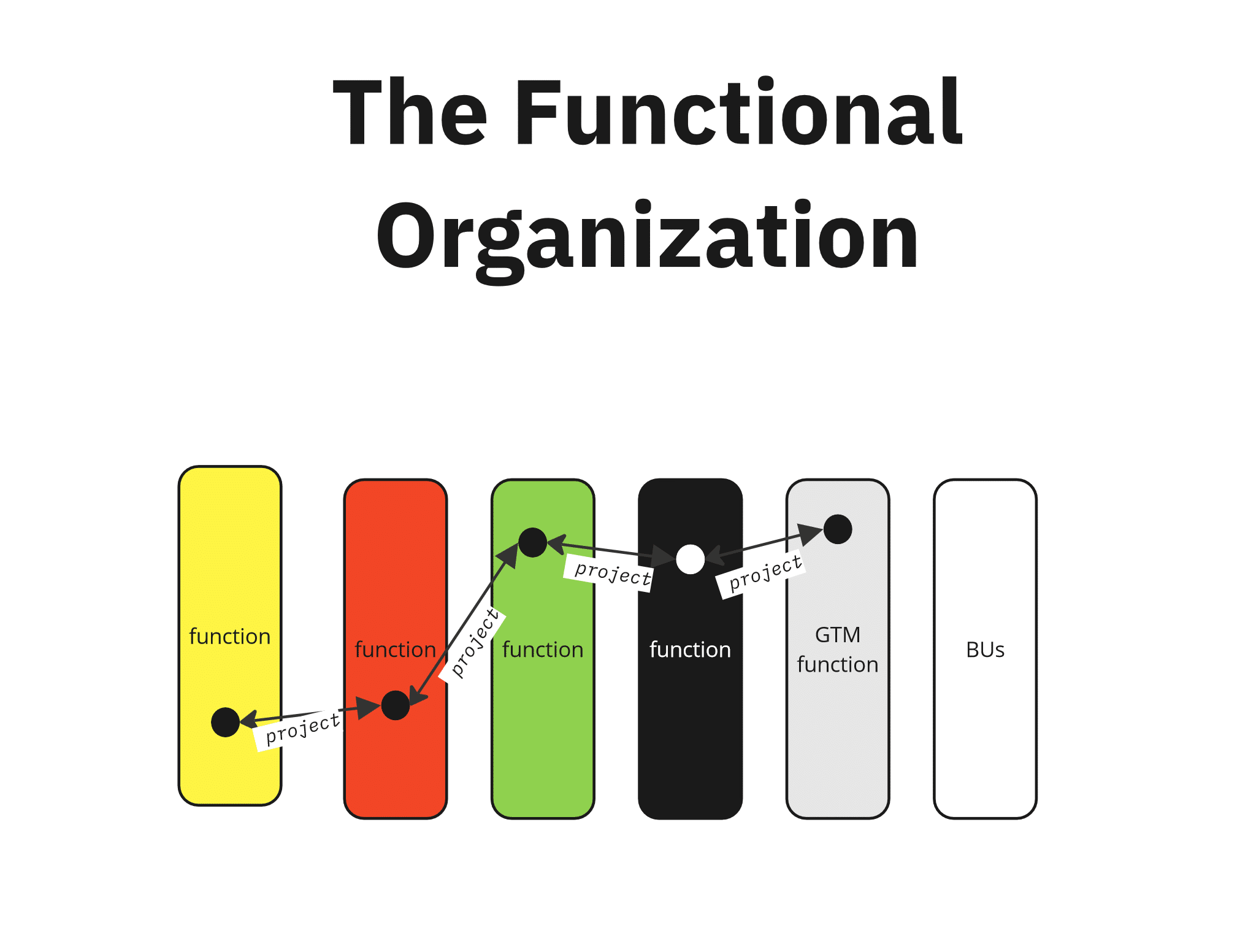

Functional Organizational Structures

Historically, businesses have relied on functional organizational structures. These structures divide companies into different departments based on functions, such as marketing, finance, and the various elements of production.

In purely functional organizations Business Units (BUs) or production lines are treated as separate “functions”. For instance, in a manufacturing company, a business unit might be a division that focuses on the production of a specific type of product, such as automotive parts.

Despite being very specialized such product-related functions have very limited capability to be independent: such BUs don’t normally have separate P&L statements and are dependent on all the other staff functions to be provided centrally. More than actual BUs we could consider them “business lines” containing all the vertical expertise needed to produce the specific elements of the value propositions but rather incapable of working on their own, being heavily dependent on a plethora of other organizational functions.

[different colors above represent different support functions, in grey, there’s a GTM – Go To Market function]

While a functional organization offers specialization and efficiency – within departments -, this can often lead to siloed operations, where inter-departmental communication is minimal or generally hard to achieve.

Compartmentalization is beneficial in a stable business environment, specific contexts, or geography and when work can be specialized. However, it often hinders responsiveness to rapid market changes and the emergence of innovative solutions across silos.

The idea of “projects” has traditionally fostered cross-silo collaboration in functional organizations but – typically – project leaders often lack sufficient power over existing structures. People inside the organization often feel committed and accountable to their functional leaders, and projects are hard to coordinate, often necessitating complex program and project management offices and efforts.

Functional leadership is often evaluated for efficiency and cost-saving rather than innovation or customer excellence, especially for staff functions. Customer excellence is very hard to champion in a structurally functional organization because the customer is rarely considered in the organizational structure: each function serves a part of the whole. Ultimately, people work to produce an “activity”, duty, or function that alone is usually insufficient to produce the full, customer-centric value proposition.

In functional organizations, the biggest risk is therefore that everyone becomes accountable for providing a task that is not sufficient to produce customer value on its own. Customer value is an outcome that emerges from everybody diligently playing their role and is often measured only by dedicated functions such as customer service desks or voice of customer departments that can fail to communicate customer needs and priorities.

The functional organization descends directly from the Industrial Revolution and from the idea of the redundancy of parts: in a well-oiled machine you can separate the elements of production and consider people as interchangeable.

In such a setup, leadership is typically above the working group, holding authority and responsibility to guide and direct team tasks and methods.

In Merrelyn Emery’s words, such structures yield “a supervisory or dominant hierarchy” where “individuals have fragmented tasks and goals: one person–one job”. This setup can quickly lead to disenfranchised employees and tactical optimizations.

This doesn’t mean that a functional organization can still perform well and create great outcomes especially when the organization operates on a single product or on very complex and fully integrated stacks that require a deep vertical integration between different elements of a product (think of an iPhone or a GPU).

Furthermore to be a leading organization – a functional organization requires strong editorial leadership for coordination in correspondence with new product launches, or product updates. Relevant examples of functional organizations that work pretty well are Apple, recently Airbnb, and nVidia (limitedly) – links to reads and listens are provided to understand the implications from a leadership and org structure perspective of such cases.

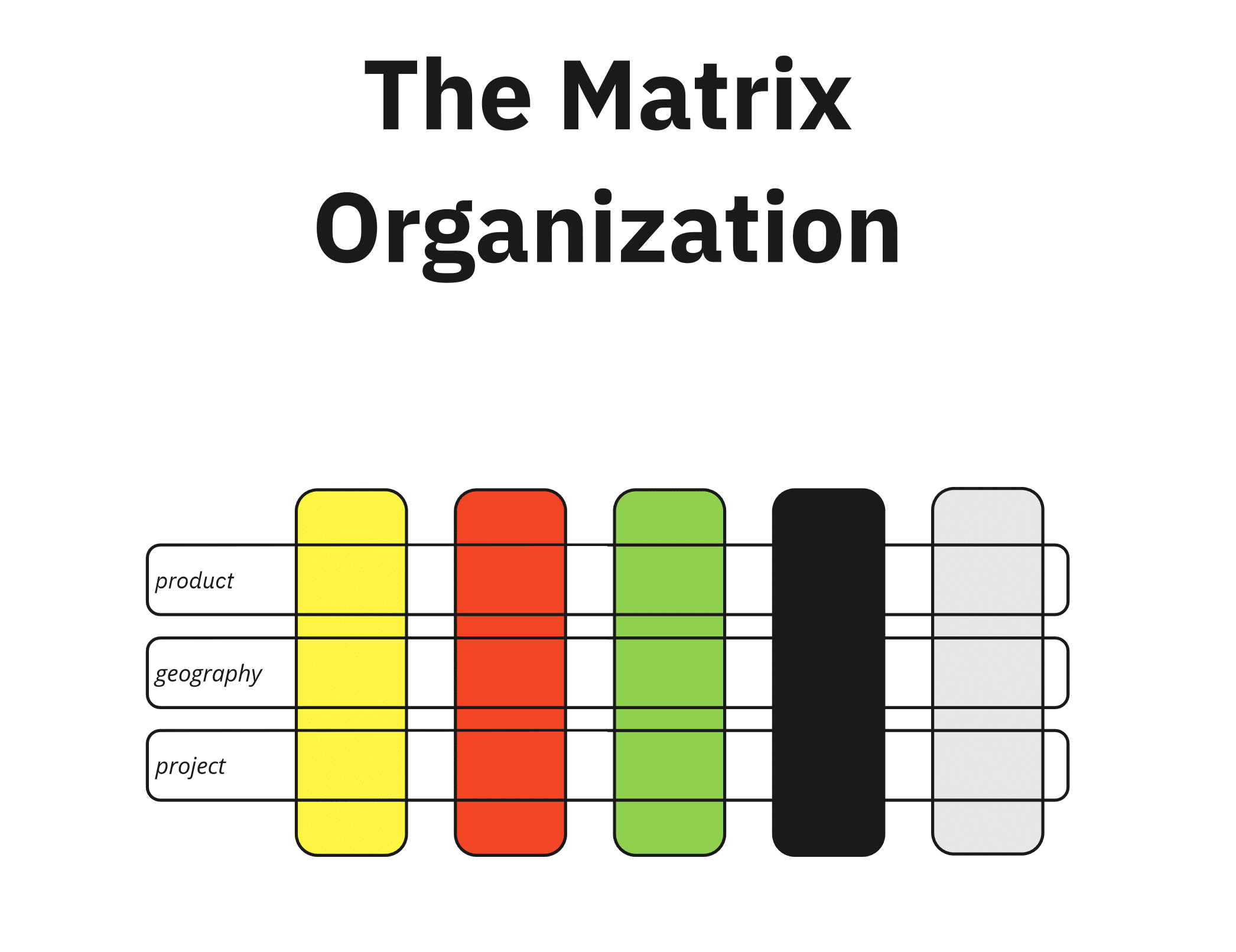

Transition to (Divisional Organizations first, and then) Matrix Organizations

The evolution away from the functional organization started from the simple idea of “multiplying” the organizational structure: as a company expands its product lines, enters new markets, or experiences geographical expansion, a so-called divisional structure becomes essential.

In a divisional structure, the company is organized into divisions based on products, services, markets, industries, or geographic locations. Each division operates as a semi-autonomous unit with its own resources, including its own production, sales, and marketing teams. Divisions are responsible for their own profits and losses and have their own divisional managers who report directly to the CEO or top management.

While it does cater to creating unique, customer-focused solutions as each division operates under the concept of a ‘full suite’ line, it also implies the duplication or reduplication of support functions – leading ultimately to resource inefficiency.

To overcome these inefficiencies the matrix organization was born as a blend of functional and divisional structures. This structure combines the traditional hierarchical management of functional organizations with the mission-based approach of divisional structures.

In a matrix organization, employees report to both a functional manager (responsible for overseeing their professional development and work quality) and a divisional or project manager (responsible for the specific project or product they are working on). This dual reporting relationship allows for greater flexibility, inter-departmental collaboration, and a focus on both functional expertise and product or project goals.

In a way, matrix structures mitigate the redundancies typical in divisional organizations where each product duplicates support functions and operates almost as a separate business.

The philosophy underpinning the matrix model is that an organizational structure should encourage widespread cooperation, knowledge sharing, and communication without compromising individual department efficiency. The Matrix model indeed combines two different structures: the traditional vertical, functional structure and a cross-vertical structure that is juxtaposed on top.

This dual command structure aims to harness the benefits of both functional and project (or more generally mission)-based structures, fostering a more collaborative and flexible work environment. However, it can also lead to conflicts in resource allocation and decision-making authority between the functional and divisional managers, and eventually longer time to market, poorly managed orders, low quality linked to the inappropriate switching of key resources.

The adoption of the matrix organizational model has helped organizations depart from the rigidities and industrial mindset into a more dynamic and mission-based nature, distributing leadership to a larger number of leaders inside the organization. Still, a matrix organization caters to a command and control structure and keeps the idea that people have to be directed and are replaceable cogs in a machine, except those leading a horizontal matrix element.

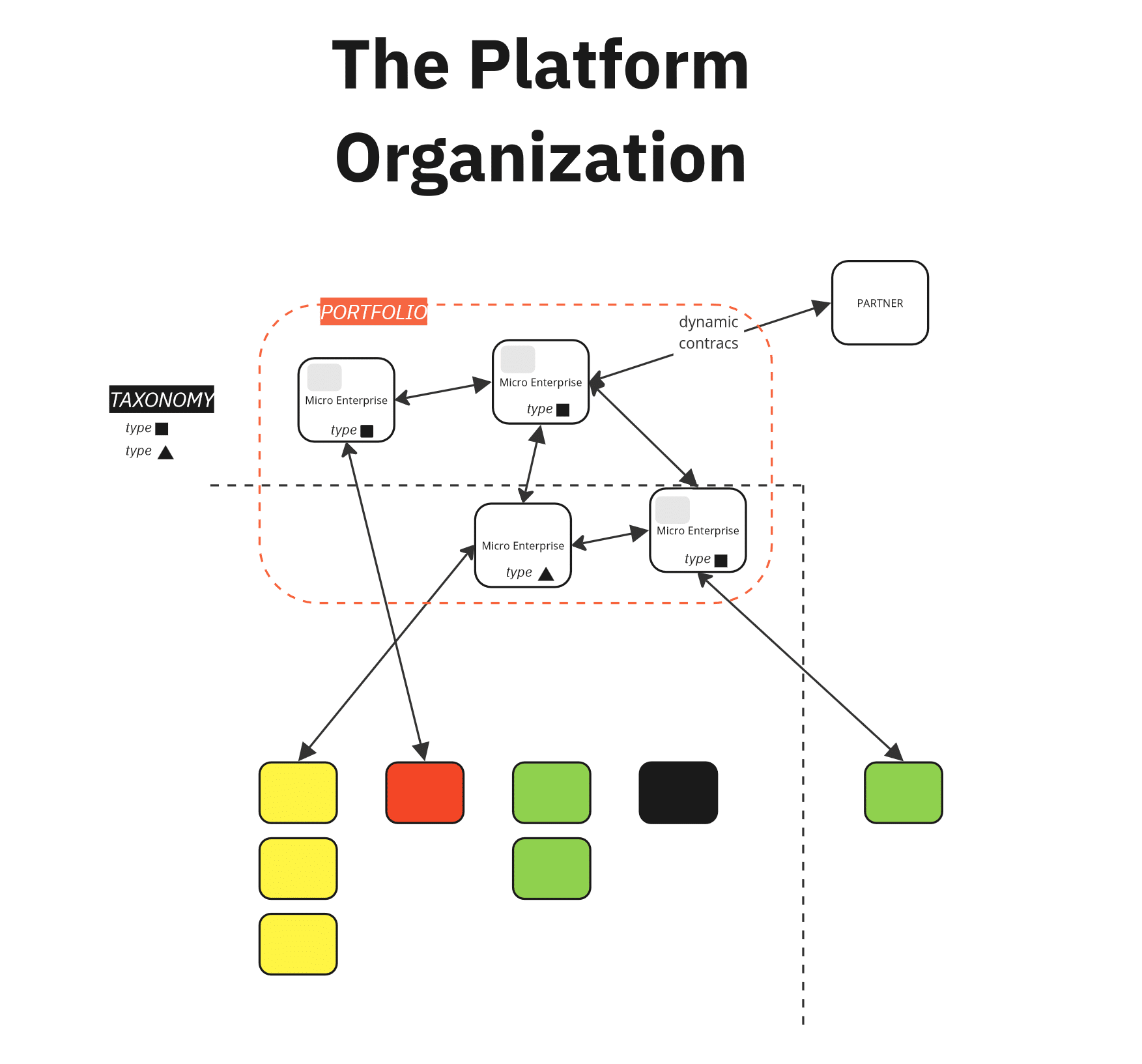

The Platform Organization

The evolution from the matrix organization into the so-called Platform organization is an ongoing trend marking the last decade as several contextual trends have reshaped markets and accelerated organizational decentralization.

Indeed the “platform organization” or the entrepreneurial organizations model is often related to a “decentralized” model as it effectively helps organizations overcome the traditional centralized approaches, distribute leadership more widely, and eventually embrace value creation models that also involve external partners.

A decentralized, platform-organization model rests on two key elements:

- independent units that normally start small, can be in large numbers, and evolve to become larger over time;

- larger support “platforms” that provide either scalable basic functions and capabilities (such as legal, IT, or finance) or enabling business capabilities (for example manufacturing capabilities, or modular product platforms that smaller BUs can use and recombine for niche markets)

Typically platform organizations also feature two more foundational differences: they invest continuously in a dynamic process aimed at creating new units and cooperate easily with external partners as they do with internal units.

In the most advanced of platform organization implementations, we also can spot a typical pattern: go-to-market capability is often re-embedded into the units. At least, even if the organization decides to provide a platformized go-to-market or sales capability to ensure coherence in the eyes of the customer they tend to not exclude independent paths-to-market for micro-entrepreneurial units so as to avoid a dark pattern of bureaucratization and scapegoating (“I couldn’t perform well cause someone didn’t sell my product).

A platform organization generally minimizes single points of failure, promoting redundancy and diverse capabilities. For instance, Haier, a leading platform organization, ensures shared support service platforms are made redundant, encouraging the formation of alternative functional service providers that co-exist and battle to serve internal customers and are also able to provide (selected) enabling services to outside customers.

In a platform organization, the concept of “projects” yields to “products,” with all the distributed divisional units aiming at producing a certain self-contained “productized” value proposition, adopting strategies that facilitate upselling and cross-selling.

Related to the latter point, defining product areas, is a good example of how to can facilitate the composability of sub-products. Encouraging working on complex customer scenarios that connect the different products in the portfolio also provides a powerful way to recombine elements of the offering to construct new value propositions.

In a recent post titled “Multi-Product Portfolios: Creating Bundles and DIY Platforms” (link) we covered strategies that can facilitate such product composition in such a platform organization context.

Why Platform Organization Now: the key advantages

Adopting a platform organizational model right now offers compelling advantages, given the current nature and evolution of markets. Today’s market landscape demands agility, responsiveness, and the capacity to continuously innovate while leveraging digital capabilities to create new products and services.

The Platform organization model emphasizes the product/service as the most vital element: small units produce a particular product or service, while internal platforms specialize in enabling services for internal units and sometimes third parties.

By creating clear, actionable interfaces, the platform organization is structured to easily integrate with external – not just internal – contributors, something that is vital to align with the growing importance of business ecosystems: often, the birth of an internal enabling platform is subsequently externalized to cater for the birth of a third party ecosystem of partners.

On this line, a few years ago, speaking about how the single product/platform unit works in Amazon’s operating model (Amazon is definitely a platform org in some ways), Ben Evans noted that due to clear, modular interfaces:

…atomised teams don’t actually need to work for Amazon. If the constraint to the model’s growth is how fast you can hire product teams and sign supplier agreements, letting other people do it for you and charging them a margin (and of course the internal teams also have margin targets too) lets you scale faster and with less risk.

The Platform Organization eradicates the outdated silo structure by allowing departmentalization only when tied to profit and loss responsibility, ensuring every part is accountable for their commitments.

A notable aspect of this model is the capacity for various parts of the organization to seek external help when in-house solutions fall short. Considering that your competitors can source competitive services externally, it’s wise not to constrain your product units to only consume internal services that may lose competitiveness. Thus, the Platform Organization is a great antidote to bureaucratization and the accumulation of organizational and technical debt.

Similarly, internal capacities can grow into customer service units to serve the wider market. Why impose arbitrary constraints on units when unnecessary? Why bar access to the market if no strategic advantage is gained from remaining internal?

This structure also simplifies inter-departmental agreements and encourages investment in fostering new connections within the organization.

Adoption Examples

Platform Organization adoption stories abound, especially in the software sector where there’s a relatively simple way to map the organization’s artifact with the software product artifacts. We covered Hubspot recently on our podcast first – with an interview with VP of Platform Ecosystem Scott Brinker – and then with an article on Designing Extendable Platforms. Solid frameworks for structuring stream-aligned teams along with platform teams have emerged clearly in software-intensive industries (check Team Topologies) but the opportunity to adopt a platform organization in a non-software-centric context is huge.

This is demonstrated by companies like Haier with its RenDanHeYi, the original inspiration and the partner behind Boundaryless’s 3EO model. Haier, a true platform organization sustaining nearly 4000 micro-entrepreneurial units adopted a platform model over 10 years ago, helping them deliver the niche innovations that made the Chinese giant an absolute category leader in household appliances.

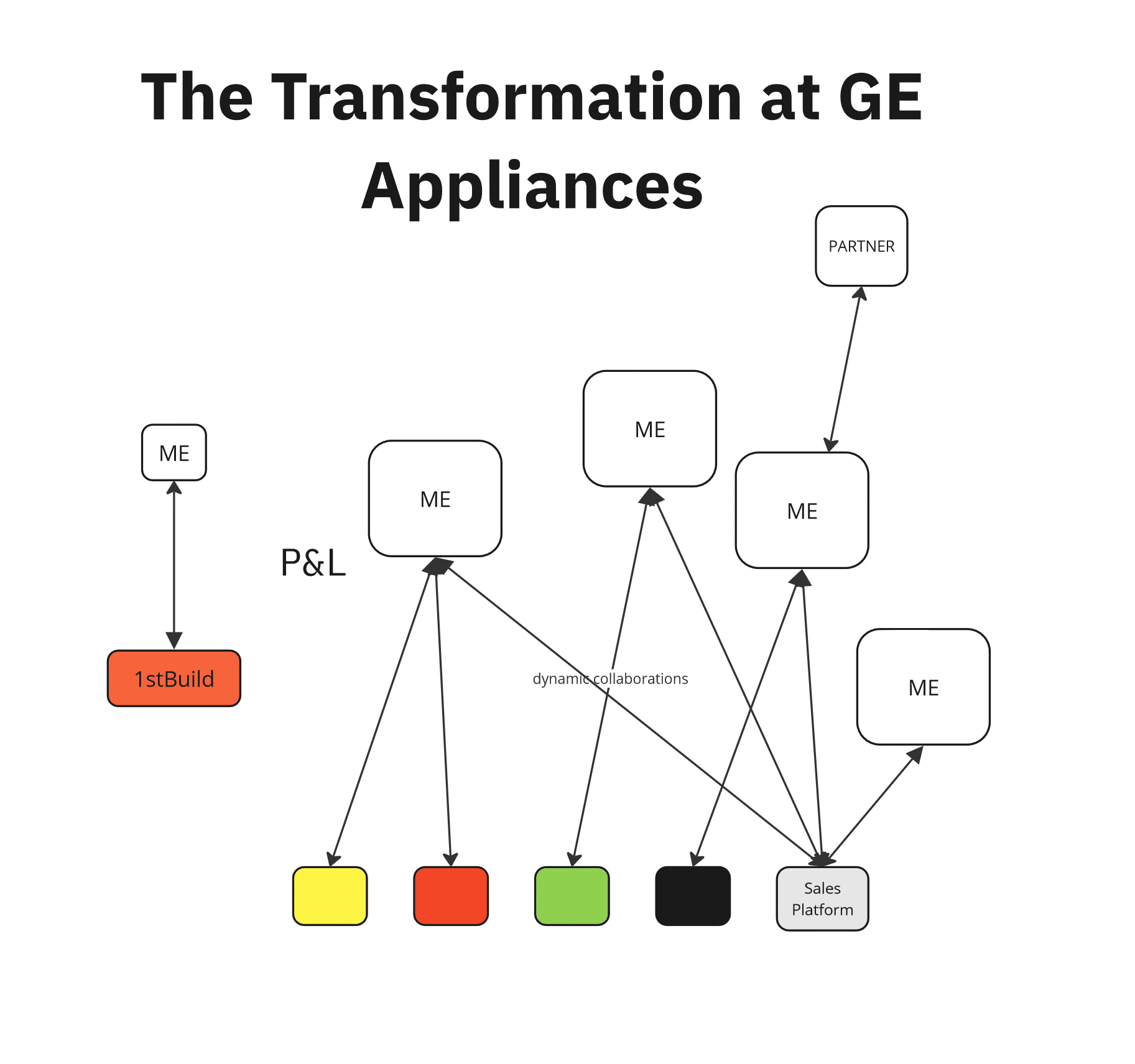

One of the most interesting and relatable examples that one can make is that of GE Appliances. Following its acquisition by Haier in 2016, GE Appliances embarked on a transformative journey, marked by record-breaking performance between 2016 and 2021. The company restructured its organization a-la-platform, adopting RenDanHeYi, with centralized GTM sales and fostering dynamic collaborations between support structures and micro-enterprises. An innovative unit called First Build was established to focus on product transformation and researching user needs, free from the constraints of profit and loss responsibilities to offer a space for the organization’s entrepreneurs to experiment in touch with customers.

This period saw the transformation of core product lines into independent micro-enterprises, each responsible for its profit and loss, and the creation of 14 additional micro-enterprises. GE Appliances also reimagined its branding strategy to accommodate multiple brands and introduced a revenue-sharing, performance-based compensation model typical of RenDanHeYi and a perfect fit for Platform Organizations. This focus on innovation and customer connection, especially through First Build, marked a shift towards a more dynamic, decentralized, and innovative organizational structure and has helped the – once suffering – US giant regain a leading role in the US market.

Another example that comes to mind is Flagship Pioneering’s with its “Process”: an approach that, by combining venture funding with shared enabling services, allows them to create 10 new “ProtoCos” (prototype companies) every year that aim at becoming platforms that enable product innovations in a key vertical space. This process helped Flagship Pioneering create an ecosystem of forty companies (started as ProtoCOs) to help the organization thrive Navigating the Polycrisis.

In our own experience at Boundaryless, we’re helping customers transition towards a platform organization model and we can share two more first-hand examples.

The first concerns a company mainly engaged in packaging manufacturing. As part of this transformation, they’re piloting a new operational model featuring the conversion of their logistics capabilities into a Shared Service Platform (SSP) and the packetization of some of their pretty rare digital printing capabilities into a micro-entrepreneurial unit that brings on-demand printing services to the market – among other experiments.

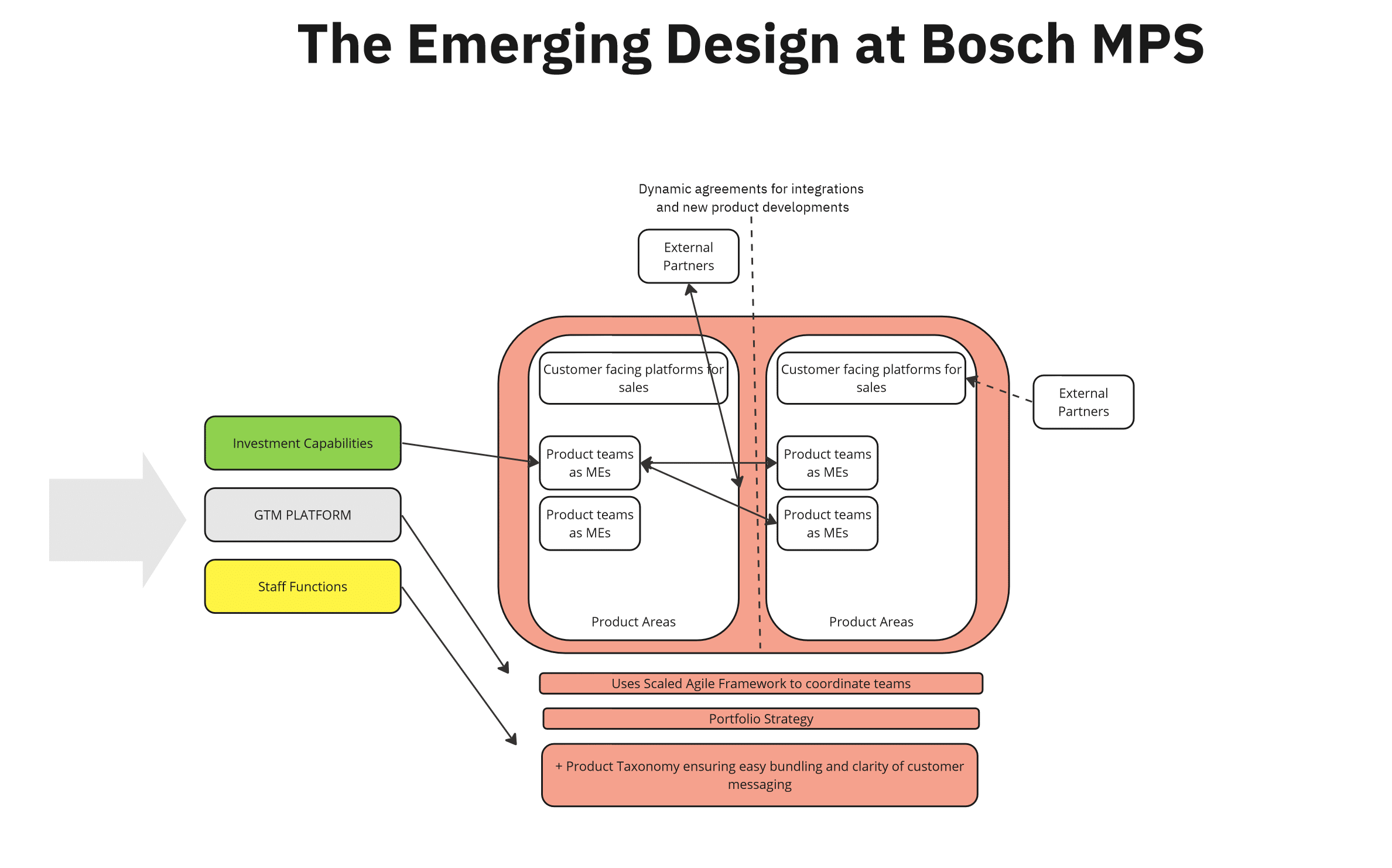

In a second example, we’re currently working with Bosch Mobility Platform & Solutions (MPS) in India. MPS is undergoing a digital mobility transformation on a global scale with significant investments. MPS is building a complex product strategy involving several products and enabling platforms and needed to evolve an organizational structure that can effectively support numerous product teams with shared services and capital allocation. In this context, the organization is creating not only shared service platforms for investments, staff functions, and Go-To-Market/Sales but also encourages product teams to operate as Micro-Enterprises once they have passed a certain validation threshold. These product teams are grouped in product areas that also feature dedicated customer-facing platforms for end users – such as fleet managers – to directly configure easy-to-bundle underlying modular products to deploy on their fleets.

Accompanying rigorous work on portfolio strategy and product taxonomy – in a way that makes products easy to recombine and strategically linked – with an underlying platform operating model makes organizations ready to achieve tremendous results.

Key Adoption Challenges and Paybacks

Despite being extremely promising, adopting platform organization models is not a walk in the park for existing organizations that rely on functional or matrix structures. Platform organization models are ideal for organizations that seek to grow either organically or by acquisitions, thus diversifying their market presence, and developing a complex product portfolio with various partners.

Adopting such structures needs a few essential elements:

- strong leadership buy-in, openness to failure in new ventures, and rapid evolution – a flexible organizational structure

- a culture of accountability and ownership, built upon refreshed skills and literacy not only in digital product design, and technological evolutions but also in business modeling, customer discovery, and – not least – deep self-management capabilities like decision-making, collaboration, and distributed coordination.

- a strategy-making process and a series of artifacts that allow the collective understanding of the portfolio of value propositions, and envision future paths

- an enabling technological layer that allows the organization to manage and distribute finances, expedite capital allocation, permit P&L self-management, and widespread contracting.

And, as a virtuous exchange, the efforts spent in the transition to a Platform Organization model, are repaid by massive advantages such as:

- a shared language across different team units, a product-oriented culture, augmented velocity and flexibility in adapting to market requests and challenges;

- an easier way to establish relationships with partners (and clients) through standardized interfaces;

- common taxonomies and clear, transparent rules to experiment with new elements of the product portfolio;

- a better capability to develop adaptive strategies, and experimental bets coherent with a shared vision of the organization’s portfolio of value propositions and capabilities

- more clarity at the communicative level, thus making it easier for clients and partners to understand, and adopt the solutions offered

Contact Boundaryless for advice on approaching this transition iteratively, with evidence and experiments, focusing on outcomes and aligning with your reference markets!

Simone Cicero

Emanuele Quintarelli