The 7 Key Principles of Platform Design

To design Strategies that mobilize, in the XXIst Century.

Boundaryless Team

That’s a tough question, we’re learning our way through.

As we had the chance to explain already, we’re on a quest to “demystify platform design”, somehow trying to — more generally — make Systems Thinking something easier to play with. We’re absolutely conscious that this is a complex matter, and the risk of coming up with a complicated solution to this complex problem. On the other hand, we’ve got countless feedback that a guided process has helped many to start their journey into envisioning strategies that mobilize, create new products and services, imagine new ways to develop organizations, without experts’ help!

Who’s the expert anyway, on this matter?

On our way in this journey, we realized that not everyone is ready, or just doesn’t need, to go through a step by step process from mapping ecosystems, to prototyping strategies. The diversity of contexts where this thinking can be applied is huge, and continues to amaze us.

A few months ago, this reflection brought you our first set of 12 Patterns of Platformization, a library is proving to be a very powerful tool in our conversation with adopters. It’s always good, when facing real situations, to bring the patterns on the table and reflect on the ways a particular market can be approached, and shaped for good.

Why Principles?

A natural step of this process, is to continue to unbundle this model of thinking, renouncing to the temptation of “bundling” it in more complicated procedures, one-size-fits-all solutions. The key here is to avoid creating an ever more specialised “hammer”, because “if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail” (thanks bro Stelio Verzera for reminding me this all the time).

Interestingly, by developing this method(ology) in the last few years, we’ve been able to get back to the essence of principles, and here’s what we share with you today, a (first iteration of a) list of 7 Platform Design Principles: you may want to keep these principles handy when designing strategies for the modern, complex, interconnected and digitally transformed world of the XXIst century.

Consider this a first version of your Organizational Revolutions: a short course on Market Realness, to quote, and freely iterate, on the amazing work of Oli Anderson that I’m digging into these days.

How to use these Principles?

These principles are — by far — the easiest thing to use in your daily practice of mobilizing ecosystems through platform strategies. You can apply them to everything you already do, or planning to do, such as a new product or service, a new organization you’re building, or a processes you’re evolving.

Platform Design Principle #1 — Recognize the potential that grows at the Edge

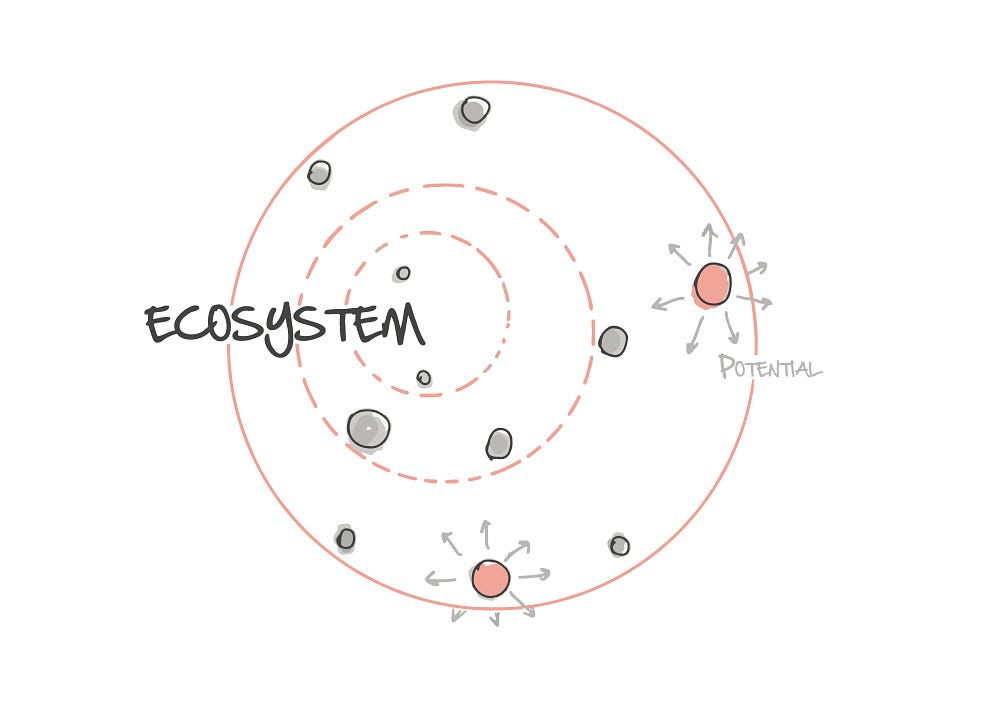

Among all the principles of platform design, this is the most important. Recognizing that small entities (individuals, teams, small organizations) have today an increasing potential to impact their own life, create powerful products and services, transform systems, is key to understand the platform model.

Why? The modern means of production fit in your pocket (smartphones) or your bag (computers), all the knowledge in the world is accessible in the open (open source software, wikipedia, youtube), and from the periphery you can summon an increasing number of centralized utilities (e.g.: computing-as-a-service, machine learning, data).

If one doesn’t consider the potential that grows at the edge, while designing a strategy, this potential will inevitably be lost.

Examples, and reflections:

- A single employee can transform the future of a company.

- Apple didn’t hire app developers but helped them to distribute their software.

- Opendesk doesn’t build furniture: fabricators (using a machine that costs less than 10k USD), are mobilized locally.

Platform Design Principle #2 — Design For Emergence

Is it possible to manufacture an ecosystem? No.

Industrial organizations in transformation struggle to understand this principle. Companies have been (slowly) coming to terms with the idea that no one should design a solution for a problem that doesn’t exist, but still have hard times understanding that designing a strategy to mobilize — a platform — doesn’t work if no ecosystem is there to be mobilized.

Platform strategies need to be designed to help an existing ecosystem to emerge, thrive and work better: platform design is the equivalent of plugging wires between electric potential. Where a potential exists, the current will flow.

Organizations of all kind need to avoid trying to design mobilization strategies for ecosystems that are not trying to exchange value already: if we agree that the real potential grows at the edge, how can we think to define what an ecosystem needs to achieve… from the center?

Platform Design is the death of inside-out strategies: never start from your capabilities, your assets, or your identity in designing a strategy, think instead how these can help you in creating a strategy that serves an existing ecosystem, exchanging value.

In the ecosystem lies the center of your strategy.

Examples, and reflections:

- The ecosystem of short-term rental existed for ages, before Airbnb: all was clumsy, complicated, and reputation was hard to leverage. Designing for this existing ecosystem helped Airbnb thrive at a scale that wouldn’t otherwise have been possible.

Platform Design Principle #3 — Use Self Organization to provide Mass Customization

In the age of the long tail, consumers demand personalized solutions to specific, custom, contextual and personal expectations. If it’s true that technology helps brands to create processes with almost zero marginal cost of production, it’s also true that traditional industrialized processes provide a near zero potential of customization.

Despite brands trying tricks to solve this issue, such as faking personal interactions with AI (remember the chatbot frenzy?), the only intelligence that can understand the context of interaction, and identify the best solution for a specific personal problem, remains the human one.

In few words, there’s no way to industrially generate mass customization, this can only be achieved by helping entities in the ecosystem to self-organize around the potential that producers have, and the expectations of consumers. Trying to respond to the expectations of the Long Tail, with an industrial, control-driven, bureaucracy is a self-fulfilling prophecy of failure: small customers will become unworthy if the cost you need to face to serve them is bigger than the economic opportunity they represent. Here’s where you want the consumer to self-organise in interactions with producers.

As one attendee to our masterclass once said, when doing platform strategies we need to “scale peerness”, our ability to connect peers in interaction. A key part of this principle resides in reducing transaction cost in self organization: as much as a strategy makes it easier to self organize in niches, the smaller the niche it will empower to exist!

In modern times, a broader market is made of many smaller markets.

Examples, and reflections:

- Airbnb doesn’t impose check-in and check out times, or furniture you need to use, or breakfast menu, all this is agreed in interaction, between guest and host, making a perfectly fit experience.

- Apple didn’t plan which set of applications were to be developed. It let developers to grow a business out of their 1000 true fans.

Platform Design Principle #4 — Enable Continuous Learning (in VUCA)

Today’s world lives through continuous disruption, change, transformation. We even coined the term VUCA (Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, Ambiguity) to describe the world we live in. In this context, everyone is looking for new ways of learning, and — reciprocally — every organization is in the learning business.

Modern organizations therefore need to offer participants a promise of accelerated learning. Their message needs to be: “if you join us on the new terms of collaboration (platform), you’re going to learn faster than outside”.

Furthermore, when offering learning opportunities, the journey must be playful, and flow-enabled: participants need to learn step-by-step, first how to interact (onboard), then how to scale and manage scaled interactions (get better), then how to test themselves in new opportunities, new contexts.

Learning must be both competitive (with peers trying to outperform each other) and collaborative, through mentoring and tutoring: helping each other works if there’s a promise of a broader market. To really learn, peers in the ecosystem need to also be allowed to give space to their true passions.

Examples, and reflections:

- Airbnb has offered thousands of people the opportunity to express their talent and passion for hospitality, helping them become professionals in the industry (as superhost, experience hosts, co-hosts).

- By offering tools, resources and conferences, Google is offering developers the possibility to scale up their operations, to focus on what they like to do (develop their content), to be part of an international community of like-minded people, and to learn from each other.

Platform Design Principle #5 — Design For Disobedience

How do modern strategies evolve when the center of the strategy moves out of the organization, into the ecosystem?

In a continuous power shift, from the brand to the consumer, and from the consumer to the ecosystem, we witness the need for the brand to give up the idea that the innovation process can be driven from a central office. It is the ecosystem that innovates, that knows which interactions need to be empowered, and therefore the organization needs to listen carefully.

Indeed, while MIT’s E. Von Hippel pioneered this idea, with the notion of “User Toolkits for Innovation” (letting users self adapt products to their particular needs), today we can talk about “ecosystem innovation toolkits”. Platform strategies should be loose enough to let players adapt their role to their specific context.

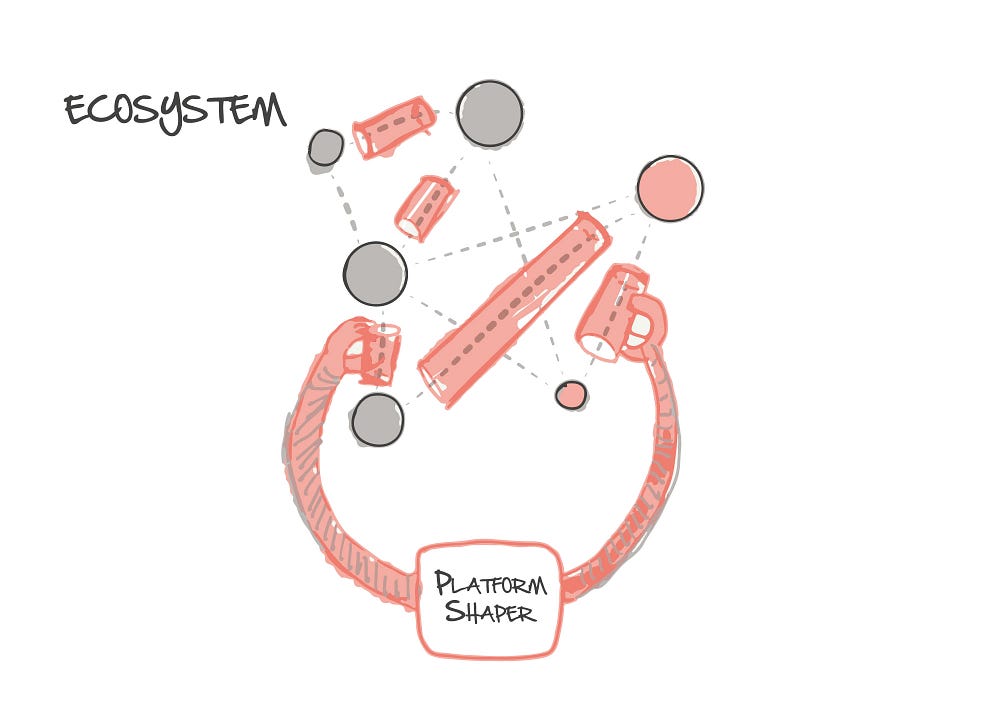

Platform designers need to “design for disobedience”, to let the players play at the edge of the rules: if a new, emergent, behavior appears as recurrent, then the platform designer needs to be there to institutionalize it, making it a feature.

This is the way platform shapers embed the Innovate-Leverage-Componentize cycle: first let the ecosystem dictate new expectations, then institutionalize them and leverage them (grow them at scale), within time make them components that the ecosystem can use, to invent something new.

Examples, and reflections:

- Airbnb has been observing the players creating experiences on top of short-term rentals for years: when it was clear that these experiences were a substantial part of the overall journey, they institutionalized them into one of the key feature of the platform.

- Let participants play loose roles: design for medical professionals (general), not for physiotherapists (specific).

Platform Design Principle #6 — Design For Interconnectedness

What happens when you stop producing solutions, and start designing ways to organize interactions in large scale systems?

This brings the organization to move beyond the very concept of a customer (somebody you design a solution for), and embrace the concept of relationships, and interactions between peers as the key element of business.

When we design to facilitate interactions between producers and consumers of value, we need to intentionally design with, and for both parties. As these parties might be in conflict (trying to maximize their outcomes), we’ll need to make sure to reduce frictions in the relationship, and make them ready to embrace the interaction.

This boils down to reducing the potential conflicts of interest (by helping them to find a common and fair ground), and to make non-zero sum games possible. If the value we generate in the exchange is greater than the original sum of needs and potential, this normally makes the interaction extremely more valuable.

Examples, and reflections:

- In a marketplace, when two parties interact and generate positive reputation, the sum of the value generated in the interaction goes beyond the value exchanged in the interaction itself: reputation is a long term attractor of other opportunities.

- Ebay, uses an online mediation service to ensure that disputes between buyers and sellers are set, in a way that is perceived fair to the parties. This increases the willingness to trade.

Platform Design Principle #7— Let go the identity, identify with the whole

When trying to capture the opportunities of a connected economy, and world, brands and organizations need to understand that they need to let go of their identity.

This means losing control, therefore potentially renounce to use a particular brand because the brand may be perceived as conflictual with the ecosystem (for example, by competitors that a platform shaper might want to transform into providers).

Renouncing to the brand can also be a way to reduce the impact of negative cases that — inevitably — will happen in a less controlled or vetted ecosystem, where, to a certain extent, the organization needs to open doors to riskiest, and therefore more accessible, players.

If the premise is to grow a bigger market, this market will eventually need to go farther and be less controlled by the organizer. The organizer of the ecosystem will need to identify more with the whole (the objectives of the whole), and think strategies (and business models) that actualize the opportunity for the whole, instead of the organizer alone.

Examples, and reflections:

- When Google launched Android OS, they deliberately kept the OS as independent by Google. They created a shared governance alliance (the OHA) and, allowing smaller players to play a role, they ended up powering a thriving ecosystem that completely transformed the whole smartphone industry.

Conclusions

From the work we’ve been doing with pioneers and gamechangers of all kinds — from the private sector to the public, from small nimble startups to the most important incumbents of our society — these principles are inherently there, they exist as an expression of the connected society we live in: choose to ignore them at your own peril.

Complying with these principles is the best way to future-proof your ideas today, and to enhance your opportunity to shape larger ecosystems of value creation, making your vision, business or organization one worth joining, for the long term.

Special acknowledgements

We feel we need to thank Millie Begovic R., giulio quaggiotto and Alex Oprunenco for the precious exchanges that — earlier on in the spring, in preparation of the work we’ve been doing with UNDP — helped us understand that, when rolling out a platform mindset in complex system, or organization, principles would have been the only solution. We certainly owe a lot to these conversations. As always we owe a lot to many from our community!