The Evolving Future of the Platform Economy

How Technological trends and a new landscape of Risk will reshape the network-based economy of the next decade.

Boundaryless Team

In this update, we share the latest research notes we developed in the process of revising our forecast about the future of platform-ecosystems thinking and its application. It was in January 2019 the last time we provided a relevant update on this and that post is still a relevant premise to this: we suggest the reader give it a read, especially as it introduces some basic elements such as the C-Z transformation of the Value Chain and the set of strategic platform plays that are adopted by aggregators for the transformation (moving away from mass-market to personalization by interaction, adopting standardized transactions, providing SaaS to simplify a business process, aggregating demand and supply, create identity and reputation systems). The blog post Understanding Platforms through Value Chain Maps and the Platform Design Example explained (here we use the same breakdown of six platform plays that we use below in the post) are also suggested read for the reader that approaches this for the first time.

A more thorough review and framing of the content introduced in this post is available on our new whitepaper.

Looking at the new Marketplace dynamics through the Value Chain

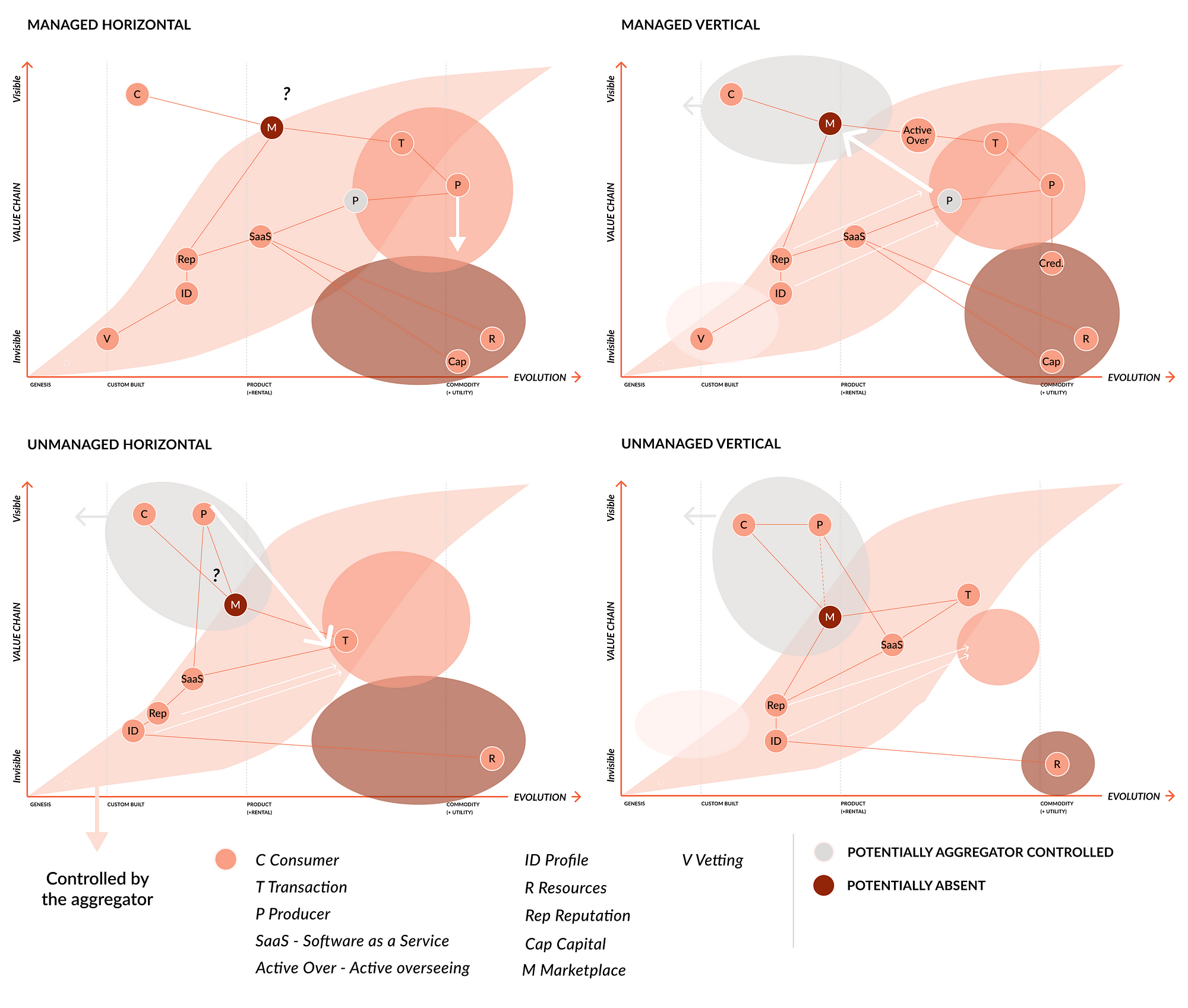

As the loyal reader will recall, in our recent post “Managed & Vertical Marketplaces: impacts on the shape of the Ecosystemic Organization” we explore how the pervasivity of marketplaces is currently expressing itself in four major “quadrants”, through two major axes, the one going from unmanaged to managed and the one going from horizontal to vertical.

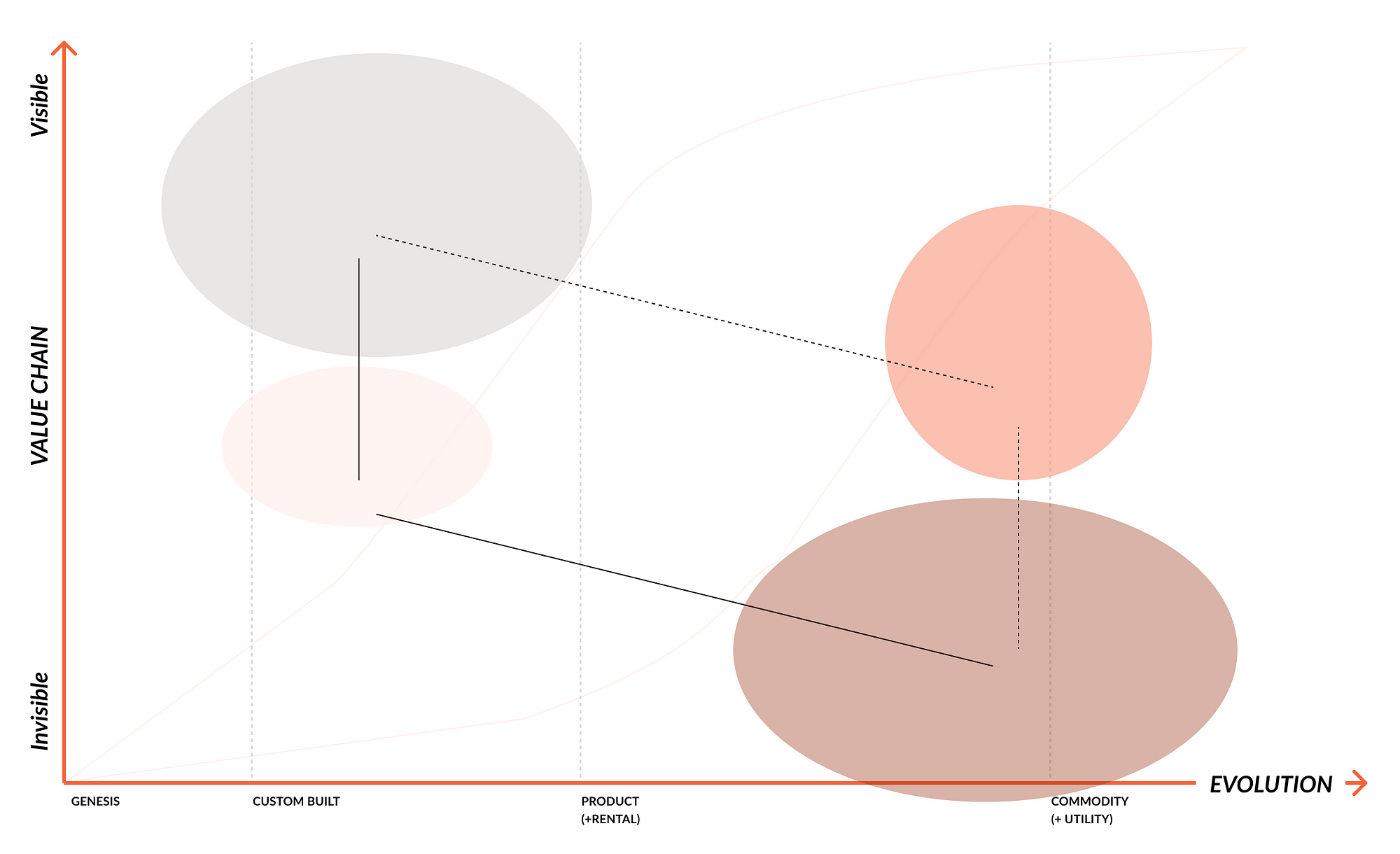

If we look into this breakdown through the lens of Wardley maps — as we did extensively in the past providing our framing of the C-Z transformation of the aggregators’ Value Chain through the Six Platform Plays — we can provide an overview of the most striking differences in terms of value chain shape, of the four categories that emerge from the breakdown mentioned above.

If we start with the earliest interpretation of a marketplace, the good old unmanaged-horizontal (U-H), of which the original Airbnb can be a good example, we have marketplaces where all the platform plays are substantially applied ending up with a Z-shaped value chain in confrontation with the typically C-shaped industrial value chain.

In U-H marketplace-platforms we have the platform to control essentially five key elements of the experience (the pink area): the marketplace (M), the transaction (T), the Saas (Saas), the reputation (Rep) the identity (ID) layers. The experiences provided are heavily dependent on providers and consumers finding each other: allowing disobedience to happen is crucial on these marketplaces as participants need to tailor their experience and generate personalized interactions.

In the case of managed-horizontal marketplaces (M-H) the changes are not that significant except that the producer (P) is normally commoditized heavily (is indeed on the right of the spectrum) and can even be substantially controlled. These types of marketplaces are much more dependent on a reliable and replicable experience both in terms of product and pricing. A good example could be that of Uber, where drivers have no differentiation between each other and can’t set the pricing on their own. In this case, vetting becomes more important (to ensure the quality) and access capital is normally a decisive factor. Sometimes the marketplace itself is not really visible to the user (again, Uber turns out as a good example). In this context PP2 (Bring producers on top of the Value Chain) and PP6 (Aggregation of demand and supply) are only partially applied.

If we continue exploring and we move into managed-vertical (M-V) space the key difference with the managed-horizontal value chain goes through a more prominent role of the SaaS as an element of value proposition for the producers. The more specific and vertical market that such marketplaces address indeed more often offers the possibility of marketing a so-called single player value proposition where professionals can see the SaaS offering as a product (this is a space that can more easily include B2B propositions). In this space active overseeing (Active Over.) of the transaction is also frequent and credentials (Cred) are also sometimes leveraged by the organizers because of existing regulations (for example in healthcare, education, etc…). Similarly to the above, in this context, PP2 and PP6 are also partially applied.

Finally, if we move back to the unmanaged but this time in the vertical markets (U-V), we see a pretty similar value chain to the U-H with the same positioning of SaaS as a product to attract producers. In some of these spaces, the producers are very independent and sometimes the marketplace feature is less prominent: the producers are the real targets of the platform and they are often deemed capable to attract their demand autonomously. Some of the so-called passion economy emergent platforms, especially those related to media, and content creation (eg: Patreon, Substack) fall into this category and drop the marketplace feature almost completely. Others such as Etsy maintain the marketplace feature actively but focus widely on the producers. In this context, PP6 can therefore be considered often partially applied.

Control and Commoditization

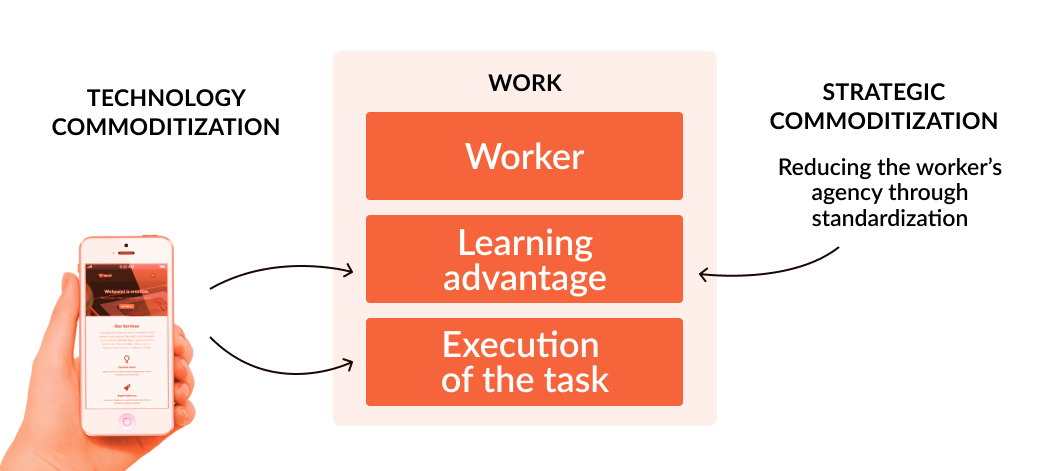

According to platform thinking expert Sangeet Choudary that we recently interviewed on our Podcast, on top of the just described value chain and market unbundling and re-bundling dynamic, two key forces also are at play in this landscape, the forces of control and commoditization. Understanding these forces — which are heavily related to the nature of the work that these organizations are facilitating, can help us frame better the context.

A key aspect to understand when looking at control and commoditization dynamics is certainly the nature of the work being organized by the platform. Work can be (albeit quite too radically) simplified as a mix between a learning advantage and workflow task execution. According to Choudary, commoditization operates at both levels, the one of the task (with pure automation) and the one of the learning advantage, with technologies suddenly making a certain advantage that the worker had, a commodity. A good example of the former is the emergence of self-driving cars that can essentially automate the task of driving the car, while of the latter is that of the emergence of GPS and maps technologies that, have effectively commoditized taxi drivers’ learning advantage — of knowing the city streets — opening the profession’s door to a new and larger pool of workers.

If we relate this to the picture we just shared, commoditization can be leveraged by platform owners mainly in the case of managed marketplaces, and mainly in horizontally managed one, because the more vertical the space becomes, the nicher the expertise and therefore assumably, the harder is the learning advantage to be commoditized. According to Choudary when learning advantage is harder to commoditize reputation becomes much more important, and we can more easily spot what James Currier also pointed out in a recent interview on the Boundaryless conversations podcast: the Matthew effect, the dynamic pushing participants to the network to distribute according to a Pareto distribution in income generation where you tend to have a relatively low number of “superstar producers” attracting most of the best opportunities, leaving the leftovers to the remaining vast majority.

Always according to Choudary, commoditization is not often a competition-driven, technologically facilitated natural evolution of markets: Choudary points out how substantial demand aggregation gives many marketplace-platforms the possibility to deprive producers of agency, effectively pushing them to standardize, and componentize — this being particularly true when the service being offered needs consistency, is not heavily dependent on niche expectations and it’s largely price-sensitive, with no price distribution depth. Uber seems to be an emblematic example of this trend.

According to Choudary policymaking must look at proactive standardization of supply — more than active legislation on countering monopoly-monopsony dynamics by policy — to actively prevent the emergence of such power asymmetries. The recipe that Choudary proposes, that of policymakers actively working to standardize supply in consolidated markets: for example by introducing standard listings format, exportable and public identity and reputation standards, he anticipates that the demand aggregators will be receiving broader competition from new entrants and leave the social capital generated by the market, as a public, social commons. We’ll see later in the article that such possibilities of policymaking through standardization of supply can be reinforced by new technologies and application models of crypto technology.

A Revised Marketplace Map

Following the just detailed description of the marketplace landscape we attempted to draw an updated marketplace map, following the one released in early 2019 and the one we released recently. This map provides the reader with positioning examples and details key competencies (purple) and key organizational differentiators (aquamarine) along with characteristics of the network that the platform-marketplace wants to intermediate. The marketplace map is therefore essentially divided into four quadrants, that resemble the same breakdown as the Value chain maps shared above.

The arrows on the contour represent how commoditization dynamics work versus enablement dynamics, and what are the major value drivers (efficiency versus quality-uniqueness and therefore mastery). We also provide information on what zones of the map are to be related with more easy to commoditize learning advantage (the horizontal, generally as the work is less specific) and what is the relationship between providing a consistent experience (in the managed space) versus giving space to the single provider’s reputation to create her own fanbase and therefore control directly the relationship with it.

Generally speaking, we see the marketplace-platform pattern moving from its original application quadrants (on the left, the more horizontal) into the right (vertical): the upper right is the space where most of the B2B revolution is going to happen, while the lower right is the space of the passion economy flourishing but also that of knowledge sharing intensive business ecosystems. At the vertex, the reader will also see a connection with the organizational shape that could more easily support growth: this is a topic we introduced and discussed widely in the previous research update: “Managed & Vertical Marketplaces: impacts on the shape of the Ecosystemic Organization”.

Assessing the impact of trends in technology, risk and narrative

At this point in the reflection, we need to introduce dynamic and evolutive factors that we expect to be pushing the evolution of this design and industry pattern and practice. This is radically important as we understand the pattern in question, that of marketplace-platforms, as a pervasive pattern that will reshape the landscape of organizing, the economy and the idea of the firm in the 21C. As we explain widely in our upcoming whitepaper, indeed this pattern of unbundling of the firm, and rebundling it around aggregation is to be considered operating, both inside and outside the firm, effectively questioning the very idea of differentiation between the two spaces.

For the analysis presented in this research update, we are considering two main areas of influencing trends: technology-related and risk-narrative related. For each of these trends, we will offer a quick, heuristic-based, analysis of potential impacts and we’ll derive value chain direct impacts that we will, in the end, reorganize visually for the reader’s better understanding.

Impacts of key foreseeable technological innovations on the marketplace-platform value chain

We currently believe that four main technological advancements have the potential to impact widely on the platform value chain: the further development of AI and Machine Learning systems, the penetration of crypto technologies (mainly crypto tokenization), the deployment of 5G and pervasive IoT technologies and finally the evolution of (cloud) computing beyond serverless into conversational programming.

AI impacts

The impacts of the development of more powerful usage of AI and — probably more specifically — Machine Learning can be considered of two major types: impacts on the providers, impacts on the platform.

On the providers’ side AI/ML can, of course, generate partial automation of repeatable tasks, while on the other hand provide features that can “augment” providers while performing non-repeatable tasks. Of course, AI/ML can also have a role in commoditizing learning advantages (as an example by commoditizing a large part of the anamnesis process in a doctor consultation).

As a combined effect of this, we can probably state that, if we distribute workers on a spectrum, going from:

- A. Repetitive/tedious jobs

- B. Simple jobs/predictable tasks — low cognitive load

- C. Complex jobs/unpredictable tasks — high cognitive load

We may see workers tending to the A-side of the spectrum being more easily commoditized by AI as AI-powered solutions compete directly with providers (e.g. translation, transcription, etc…) while workers tending more to the C side, would likely be empowered by AI/ML. As a consequence we can foresee AI/ML has a twofold impact: on one hand, reducing barriers to entry to the market (for consumers) by unlocking automated supply and, on the other, reinforcing polarization, Matthew effect and superstar economy trends already playing out.

On the side of the platform, AI can help oversee transactions and ensure more integrity, by helping for example with anomaly and fraud detection and identification, letting human intervention to show up only where and when necessary. AI/ML can also of course help platforms optimize for prescriptive analysis (with some degree of danger of self-fulfilling prescriptions). AI/ML can also, especially in platforms that depend on economies of the tangibles, provide effective forecasting capabilities and help with dynamic pricing, yielding and revenue management, especially if part of the inventory is perishable.

Overall, in terms of value chain impacts, we will have broader access to commoditized supply and — at the same time — more differentiated supply (superstars), higher transaction integrity and better matchmaking. As a side effect of the importance of reputation (for non-commoditized learning advantages) an affirmation of AI support tools could also grow the case for the reputation to be “unlocked” from a certain platform and made more sovereign and portable.

Crypto impacts

The uptake of Crypto technology in business and products is being actively explored now for more than a decade. It was in 2017 when Chris Dixon dubbed crypto tokens “a breakthrough in open network design” and 2018 when Ben Evans touted crypto as a potential “market reset” technology.

The crypto industry improved and evolved radically since 2017 and some essential design breakthroughs have increased even more the capability to design functions that connect both financial and governance incentives to dynamics of participation, investment, and collaboration: bonding curves, curation markets, mechanisms of voting on proposals, mechanisms of fund allocation and much more. We’ve been covering in the past how the existing — at the time — patterns of token design overlapped with the key entities and elements of a platform strategy and it’s not the aim of this blog post to go back and explore deeply the possibilities that such a landscape provides at the moment.

In the context of this blog, we mainly want to investigate the broader, systemic impact of crypto on the future of platforms and the related value chain, with a focus on core capabilities of crypto such as smart contracting, transparent data layers, sovereign identities, and the possibility to embed financial, governance and access rights into tokens.

One of the key aspects of the penetration of crypto is indeed its broader capability that crypto tokens design give designers and architects in terms of capabilities to design financial and other types of incentives into an ecosystem mobilization strategy: according to Akseli Virtanen, co-founder at Economic Space Agency and Robin Hood Hedge Fund, “Cryptoeconomics opens to us economy itself as design space.”

Dixon successfully captured the radical innovation that crypto tokens offered designers with his famous graph as follows:

According to Dixon, while traditional network effects provide a value function that grows at lower stages, only when numbers grow, as they only provide use-value, leveraging token design teams are able to create financial utility for users at the very start and let this utility diminish on the longer term when the use-value ramps up the resulting value function is flat and the proportion of financial value and use value rebalance over time. Essentially, if we couple these broader capabilities to design financial incentives in networks, with smart contracting layers that are able to execute on shared rules, including aspects of governance, this gives rise to new possibilities to see shared coordination infrastructures emerging and cooperative integration layers of which many organizations can share ownership, governance and execution duties. As an example, a group of firms could co-own a shared procurement infrastructure and a system of towns could co-own and manage a shared currency system or the management of an electric microgrid this way.

Particularly interesting from this perspective is the potential of progressive decentralization patterns — as first identified by Jesse Walden — in funding and getting off the ground shared information coordination and work coordination infrastructures. If we quote from a previous article we released on this blog:

Jesse Walden touts crypto-networks as “pioneering a new form of “cooperative capitalism” and explains that “beyond the ability to crowdsource funds from members of the network, crypto networks can compete with better-capitalized corporations on other dimensions — especially those that require high degrees of trust”.

[…] one organization may take care of creating [these coordination infrastructures] within time, transitioning the ownership and governance of a broader set of stakeholders, effectively acting as a keystone ecosystem species, at least for the time needed to get mass scale collaboration on these intermediate structures off the ground.

Another convergent capability that blockchain technology has evidently brought to attention is the possibility to create data layers where information is openly available and verified. In July 2019 PWC touted that blockchain-enabled so-called “Self Sovereign Identities”, digital identities owned by the very user, instead of being issued by a particular third party, could “represents a major breakthrough, the impact of which will extend far beyond what people typically think identity means”. As Choudary reminded us during his recent interview, the potential of open-public identity and reputation registries, which I must add, could easily be based on a crypto-token powered DAOs that brings forth the incentives for the operation of the infrastructure, may well represent part of that “standardization of the supply” trend that, according to Choudary, could help mitigate monopsony-monopoly patterns in the market, thus hindering the power of winner takes all dynamics.

In terms of value chain then, the major impacts can be identified in the emergence of the role of investor (sort of co-entrepreneurial user) and a more prominent role of the financial incentives in the value chain. Further impacts are:

- the progressive unbundling of demand aggregation from supply standardization (eg: identity, reputation)

- the emergence of co-governed shared mediation layers between firms and organizations more in general (work coordination, financial coordination, etc…)

- the overcoming of vetting towards permissionless, reputation centric selection processes

Other key technological impacts

There are two other major technological advancements that we believe may have a lasting impact on the platform-ecosystem future: 5G (and more generally pervasive, low latency connectivity in things) and the evolution of computing beyond serverless into further modularization and so called “conversational programming”: the capability to vocally and visually mix and match cloud based software components to quickly create solutions.

Let’s start from the latter: to quote Ben Basche, Senior Manager, Product Development at MultiChoice Group, the future of cloud computing can see the emergence of “an ecosystem of Intent-defined, high-level serverless components close to the user (checkout flow, online store, blog, subscription widget, dashboard, etc…)” and a codeless, natural language-based control panel on top of it, thus bringing “Software moats” to zero a consideration that is fairly resonant with one of Simon Wardley’s now-famous imaginary Twitter conversations, from 2018, highlighting how the impact of technology such as conversational programming(what Basche defines “a codeless, natural lang control plane”) might have on the application development value chain.

If we add — on top of this — the effect of 5G technology, mainly a broader penetration of real-time sensory information in complex contexts such as industrial ones, or more generally a broader penetration of connectivity across the infrastructures deployed locally thus improving further our capabilities to connect and organize it, the effects on the value chain that we can extract tell us about broader composability of infrastructures and resources on side and — on the other — an easier way for designers to move from an abstract idea of organizing into tangibly deployable technological solutions, on a much nicher, smaller scale. In a few words, deploying smaller and more niche technology solutions to organize a certain ecosystem will be increasingly possible as technological barriers will continue to disappear and access pervades all resources and infrastructures in a process of “onlinification”.

Global Disruptions and emerging narratives

We recently published a deeper reflection on a new landscape of risk and its implications on organizational evolution which we suggest the reader to explore, but for the sake of this exercise, we want to explore how three main global risk trends will impact the value chain of platforms and ecosystems.

First, the so-called “decoupling” of US and China and more generally the end of globalization as we know it, with a world that moves away from US cultural and trade domination towards a more multipolar perspective. Digital markets are also fragmenting regionally: as Nicolas Colin exposed during our podcast conversation “the illusion that digital markets will always be global” is now over with now often competing regulations that often reach beyond the country of residence of the internet users accessing digital services globally. Furthermore, according to Choudary (still on our podcast conversation), sovereign states initiatives to deploy digital — and non-digital — coordination infrastructures (in trade, logistics, finance, communication, IT and more) and that of imposing those as standards globally is going to be the place where the geopolitics of technology is going to be played in the future, as China’s Belt & Road initiative well represents.

Secondly, the Covid-19 pandemic can be taken as representative of two more major trends: an increased unpredictability level in the economy and society and the growth of narratives increasingly focused on health and sustainability. Major impacts can be expected and are already being experienced — as a major consequence of this rising unpredictability — in terms of job loss, and growth stagnation and they’re pushing towards a renowned focus on economic contexts that for long have been deprioritized: the household, the community, the city, the region, the nation. Indeed de-globalization or “slowbalization” has been playing out as a pattern since 2008: according to PIIEand “the pandemic adds momentum to the deglobalization trend”.

Massive public investments and subsidies are being currently deployed worldwide to rebuild key infrastructures and revamp the economy — many linked with sustainability and salutogenic narrative — and the involvement of citizens in the rebuilding of less brittle and more resilient production processes that can be subsidiary and integrative to the private-public dichotomy seems a likely outcome and a direction where to concentrate the productive potential of otherwise jobless citizens. Indeed, as we have highlighted already in our previous research update on the emerging risk landscape it seems likely that an increasing level of stress on supply chains can be expected as a result of the rising complexity and unpredictability and that building parallel redundant supply chain lines is one of the key strategies to pursue to ensure operational continuity.

As a result of those trends we can expect a series of value chain impacts: first a trend of relocalization and partial decentralization of elements of the lower part of the value chain (such as in manufacturing). This will play out mainly through M&A consolidation (at least on a regional influence scale), and then with increased composability, reuse, and circularity for resource optimization. Furthermore, an increased value perception in security, health, and resilience is to be expected in parallel with two major labour-related trends: more inclination towards parcelized work (in lack of traditional employment) and more interest towards entrepreneurial opportunities related with the project of rebuilding the economies of essential through a broader engagement of citizens.

Putting everything together

In putting together all the impacts we mentioned above, we will show them on the Wardley map: using such a map as a “background” will allow us to project the “zones” where most of the impacts “coalesce” in certain “areas” of the value chain.

Four macro areas of influence can be identified overall:

- Evolution of demand and supply aggregation;

- Transactional integrity, identity and reputation and abstract coordination system

- Domain-specific infrastructure towards niche organizing

- Enabling infrastructures and standardization of supply

Below we’ll explain that in more detail.

The first area, the gray one on the top left covers the most important shifts that we can expect by composing all the trends. In this area we could expect a dual direction: on one hand, traditional demand aggregation will become increasingly niche in continuity with what we’re seeing today (vertical markets) and will become more direct to customers (DTC) and more managed. In this context the consumers will receive ever prescriptive recommendations thanks to AI and data and super producers will be leveraging machine learning powered tools to increase their reputation and thrive, while others will struggle.

On the other hand, the user needs related to generating opportunities for investment and creating better resilience will be met by more complex platforms that will entail co-investing and possibly co-managing capital allocations into developing new forms of entrepreneurship to complement a stagnant industrial economy, including and possibly focusing on building resilience in the local context. These initiatives that will be increasingly focused at the community, town and regional level will need to tackle opportunities to rebuild new models for the production of key services where market failures and traditional public policy failures will happen as a result or rising unpredictability. This will happen in key social sectors such as welfare but also in the essential economy areas (food, energy, housing, micro-manufacturing, etc…).

In a second impact area, in pink, that of transactional integrity, identity and reputation and abstract coordination system, we’ll see more transaction standardization: one of the key expressions of the aggregation theory on the value chain. AI will help to ensure better transactional integrity and the standardization will expand below, including the emergence of sovereign identities and portable reputation systems based on shared and standardized protocols. Furthermore, one can foresee the emergence of system design models and engines that will provide easy to instantiate and composable elements of financial incentives design, governance models and more, such as the ones we’re seeing emerging in the DAO space, with projects such as the already introduced Commons Stack or Aragon. These newly emerging technological and model stacks will essentially power a “standardized” approach to organizing.

In turn, such domain-specific infrastructures for niche organizing — and the ones on the right in blue, the systems for transactional integrity, identity and reputation and abstract coordination — will be both connected with an enabling infrastructure, standardized supply & commodities.

This ultimate area of impact will likely see the consolidation of GAFAs as the ultimate attention and demand aggregators that will continue to tax new entrants through advertising and positioning services for distribution (especially obviously the increasingly niche DTC aggregators) and, just below that, a tumultuous standardization and commoditization of the un-specialised gig workers, coupled with the emergence of a strongly automated, remotized and AI-powered supply, both increasingly turning towards further commoditization. Here, the impact of rising unbundled digital unions and platform cooperatives can have decisive implications for the welfare of such workers but the impacts of such cooperative rebundling patterns is still hard to evaluate in the long term. On the lower part of this area of impact, it is foreseeable that key processes with strong social and environmental footprint such as manufacturing, logistic, trade and finance will evolve towards more interoperability and standardization. This interoperable infrastructure — based on shared standards and shared coordination structures — will offer “pluggable” opportunities for public institutions, entrepreneurs and cooperatives to cooperate and develop last-mile regional/decentralized access nodes (see the green zone). Natural resources and materials use will need to be based on the new and emergent ways of flow-based accounting for circularity such as with Kate Raworth’s doughnut economics of which we’re starting to see uptake prompted by the pandemic. In this area, uncertainties abound related to the effective development of international agreements to tackle climate change and environmental degradation. Today’s rising geopolitical instability and the strong uprising of nationalism and regionalism trends points out that the possibility for such sustainable and circular coordination infrastructures to emerge according to the sphere of the political influence of specific geopolitical powers such as the US, China, the EU, and, to some extent, Russia and India. The analysis we just provided leaves us with two major areas. One connects the gray, pink and brown dots through the dashed line and represents the area of the market where mainly intangible and globally tradable products and services are going to be exchanged. In this part of the market, demand aggregation is going to become nicher (vertical) and managed, with more reputable super-suppliers leveraging AI. Here the market will largely be convenience focused, and the need to increase use cases will push for inter-platform interaction and composability which is going to increase thanks to common IDs, reputation and make the whole idea of aggregation more transient, and democratic. The other route, which connects more profound design challenges that involve new forms of finance, collective investing and managing infrastructure and production, that is definitely more local, citizen involving and niche will be the space where a profound reinvention of the economy — in terms of resilience — is bound to happen as an answer to a newly emerging risk landscape. Impacts on the marketplace value chain As a further process of integration of these insights we want to offer a visualization of how these macro trends play out in the four quadrants making the marketplace map. Impacts on the value chain will be common to the whole scope of the pervasive, marketplace-based organizing landscape, although depending on the characteristics of each quadrant the impacts will be playing out slightly differently. It’s worth noticing that in the horizontal space, where specialization is less important, and learning advantages are easier to commoditize, producers will be pushed towards commoditization more easily and actual p2p marketplaces will increasingly be replaced by the prescriptiveness of algorithms that can choose the right option for the customer based on increasingly available data. At the same time the push towards niche organizing will likely reduce the applicability of horizontal marketplaces overall. On the other hand, in the vertical space where specialities and niche capabilities of producers may be more important (in B2B for example), we’ll see a radical abundance of specialized SaaS offerings aimed at augmenting a professional that is made more visible. In the same way, the pressure to achieve more composability in platforms as a way to, on one hand, provide more inter-contextual experiences and paths of value creation for super producers to develop their capabilities and, on the other hand, to allow rapid prototyping of new experiences in the face of unpredictable changes (the pandemic being a good example) will likely push for the unbundling of identity and reputation and their re-bundling into the shared work-coordination structures that will serve as interoperability systems and as “wrappers” of the access to more tangible resources (from heavier industries).

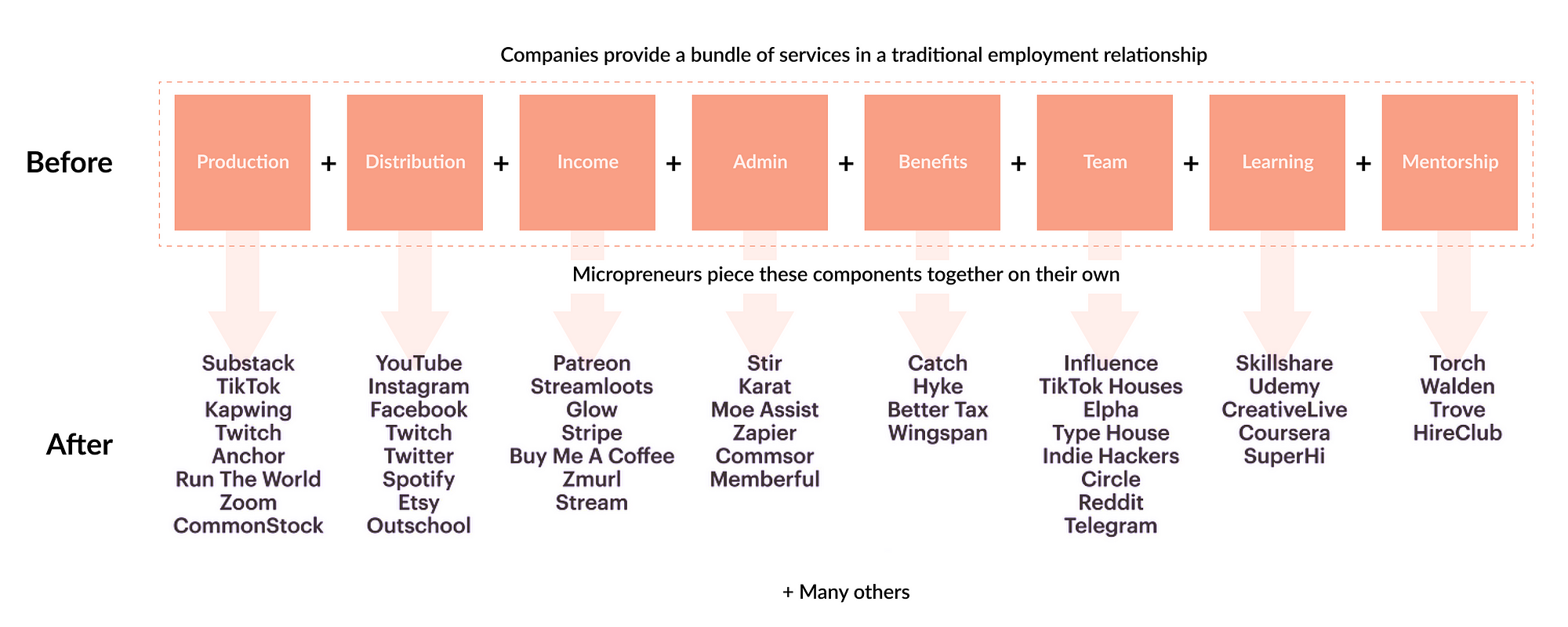

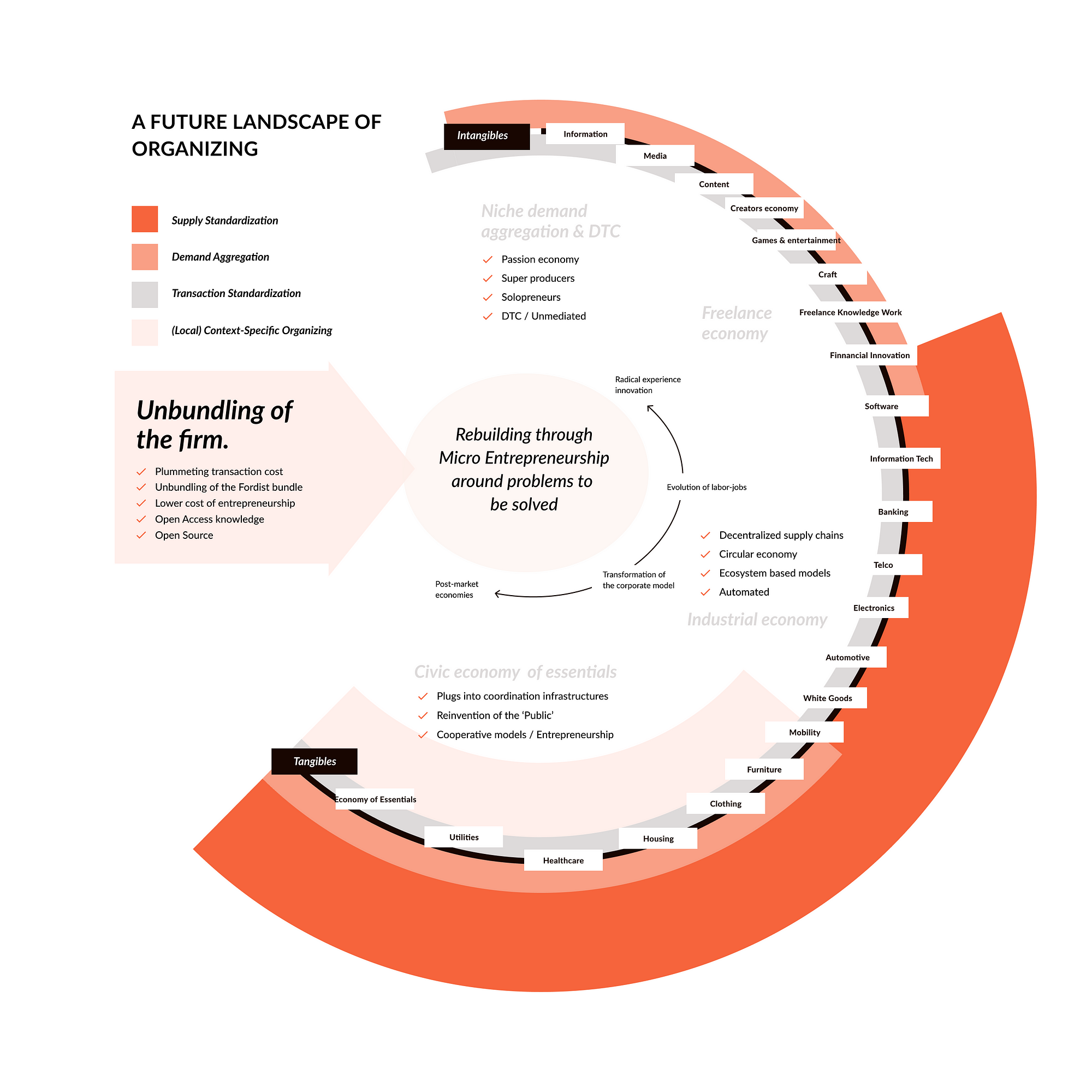

If we try to tie everything together, based on a foresight exercise that projects our grounded assumptions in the future all at the same time, we can imagine something similar to what follows. The very basic force that is putting things in motion is definitely the unbundling of the firm. As we have already explained, plummeting transactions cost and the progressive unbundling of the Fordist bundle, coupled with the incredibly pervasive nature of open knowledge and open software makes the micro-entrepreneurial unit ever more capable to rebundle markets, and organizations around problems to be solved. We’re seeing indeed this trend happening already in the corporate world, with most of the protagonists of the rampant digitized markets adopting radically unbundled organizational models that allow teams to explore opportunities and organise around them. But micro-entrepreneurial teams are — of course — also now thriving in the economy of intangibles, with the powerful emergence of the passion economy, and the disintermediation of industries such as media and news as brilliantly explained by Li Jin in her thesis around the unbundling of work from employment. Despite the revolution of the micro-entrepreneurship is still slow to be expressed in the context of what we called here the civic economy of essential (in care, welfare, local food production, micro-energy and similar civic context key processes) key experiments — often led by far-sighted corporates or cooperatives — are being run: the thinking goes to organizations such as Burtzoorg, reorganizing care around local nurses’ teams or Participatory City, fueling a blossoming of an economy of small businesses, active in the context of essentials, around a shared infrastructure investment (warehouse, tooling,…) and regenerating part of the city of London in the process. The picture above illustrates how dynamics of niche demand aggregation will be playing out almost everywhere, probably except for a part of the economy that will still rely on traditional distribution — although business models based on access are rampantly being experimented. Transactions standardization as well will likely be a pervasive trend, with the rapid consolidation of payment systems — Stripe is a good example — and the emergence of interoperable work coordination structures to facilitate interaction between small and big firms, and between externally focused firms and their ecosystems. Supply standardization will be inevitable across the whole spectrum of accessing tangible resources — for the reasons we explained above (peak resources, environmental degradation, dynamics of competition…) and the interplay with local organizing will be essential to allow local entrepreneurs to access infrastructures and resources provided by the industrial players, recombine them with systems of funding, governance and finance, and create locally managed and locally optimized organizing solutions. This interplay between an ever more consolidated and, at the same time, bounded by its environmental impacts, industrial economy, and a civic economy that extends, contextualizes and implements last-mile distribution, and recombination it’s probably the sweetest spot for organizational experiments in the coming decade. These tools will, in turn, enable another evolution towards a more domain-specific infrastructure for niche organizing (light pink): instances of the standardized systems depicted above in the blue space will be implemented and run contextually (for example locally) to power the new aggregation strategies that also involve managing investments and assets and collective governance we depicted above. These contextual work coordination infrastructures will be powered by niche and contextual data and by Platform as a Service AI engines that will use specific domain models training. As an example, aggregation systems of co-investing and co-managing regional regenerative agriculture plans, or the development of shock resilient microgrids, or even city-specific systems of welfare and care will need AI to be trained on local specific data and local specific models.

These tools will, in turn, enable another evolution towards a more domain-specific infrastructure for niche organizing (light pink): instances of the standardized systems depicted above in the blue space will be implemented and run contextually (for example locally) to power the new aggregation strategies that also involve managing investments and assets and collective governance we depicted above. These contextual work coordination infrastructures will be powered by niche and contextual data and by Platform as a Service AI engines that will use specific domain models training. As an example, aggregation systems of co-investing and co-managing regional regenerative agriculture plans, or the development of shock resilient microgrids, or even city-specific systems of welfare and care will need AI to be trained on local specific data and local specific models.

A new landscape of scalable organizing