Understanding Platforms through Value Chain Maps

Why is a Platforms’ Wardley (Value Chain) Map Z-Shaped? An essay to explore the convergences between value chain mapping and aggregation strategies.

Boundaryless Team

Premise

This is one in a series of blog posts, aimed at providing a unified market theory to spot opportunities of aggregation, (platform strategies) that modern markets offer.

This post will continue exploring the convergences between value chain mapping and aggregation strategies.

It will also relate value chain analysis to our ecosystem scanning techniques, tools that we use to preliminary explore ecosystems, searching for potential patterns and gameplay.

By reading this post, you’ll, therefore, understand how to:

- map an existing context that you want to transform, shape, disrupt;

- plot the elements you’ve found on a value chain map;

- identify the key elements of your platform (aggregation) strategic gameplay.

Again, a special thank goes to Ron Kersic for the invaluable help in unearthing these new insights. I also need to mention the amazing work done by Bill Murray with Liberating Platform Organization report (currently restricted to Leading Edge Forum members).

A slightly different understanding of a Value Chain Map

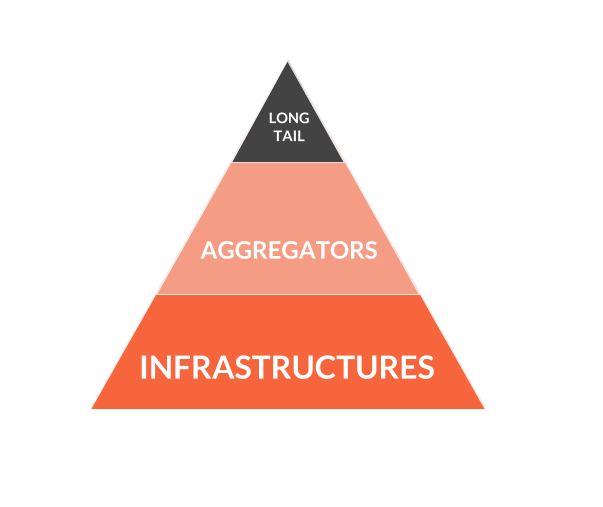

During these two weeks of analysis, as we tried to map recurring gameplays, and existing patterns in designing-for-ecosystems (platforms) we ended up figuring out a slightly different way to overlap our magic triangle — my conspirator Ron Kersic is starting to call it the Cicero’s Triangle, maybe it’s a handy idea — with a Wardley’s map landscape.

As the loyal reader might recall, two weeks ago we came up with the following idea, correlated with some high-level assumptions (we suggest you read the post for context):

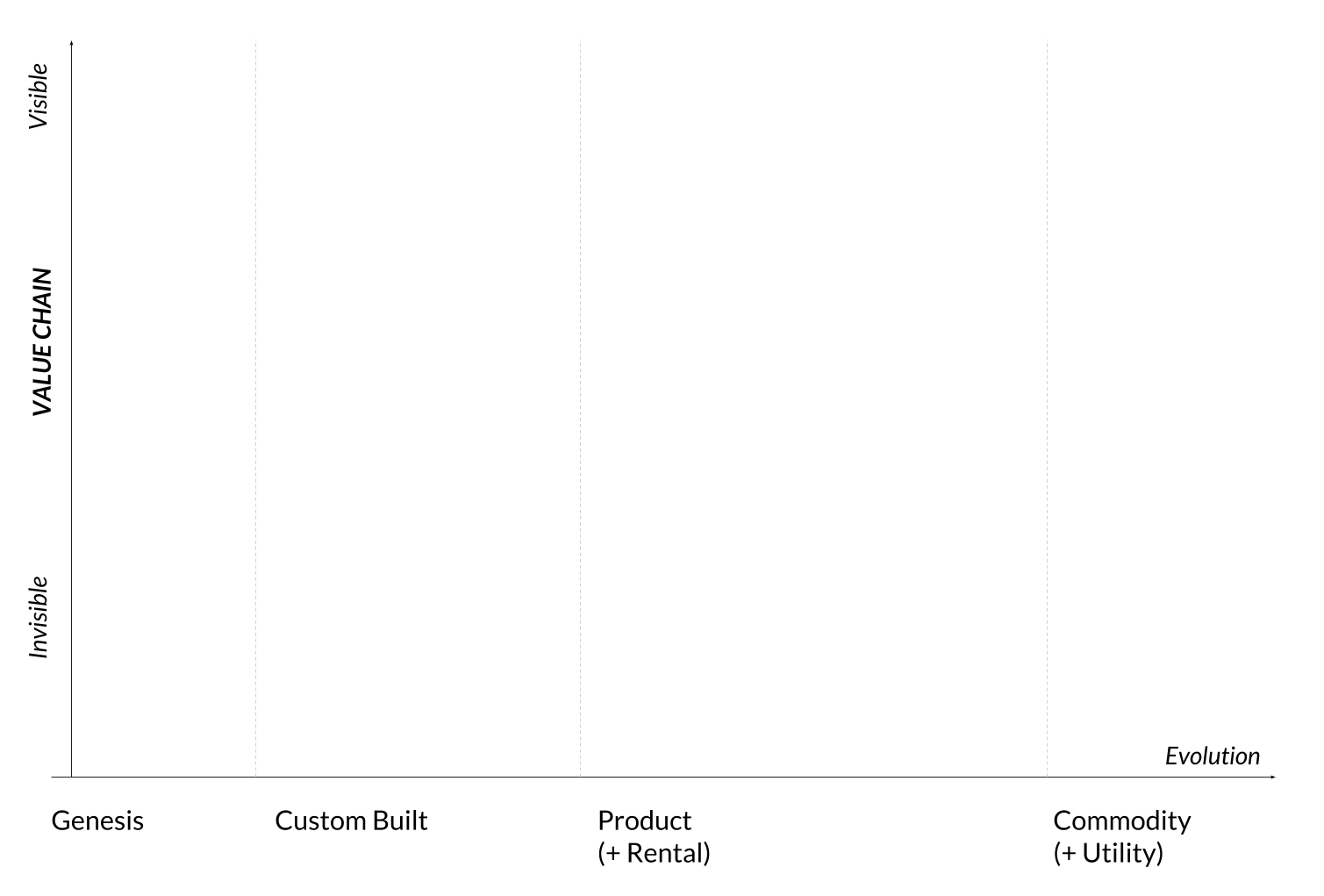

But as a result of our latest research, we’re now using this slightly adapted way to plot it:

Picture 1 — A new understanding of the three layers from Cicero’s triangle, in Wardley’s value chain map landscape

Why the change

As we already said in the previous post, this zone breakdown of Wardley’s map is to be considered more a “rule of thumb” than a hard structure. On the other hand, we felt that the original breakdown was not 100% correct, essentially due to the three following reasons:

- infrastructures and enabling elements (utilities, components) are rarely visible but they are in some cases, for example in value chains targeted to remixers/hackers/makers — in a direct infrastructure-to-user relationship;

- technology-powered mass customization, when characterized as low marginal cost process (eg: internet-enabled sneaker customization, or parametric design), also brings long tail consumers directly in touch of a commoditized technological infrastructure — in another direct infrastructure-to-user relationship;

- on the other hand, it’s rare, but long-tail markets can sometimes cover the full stack: think for example of current ultra-local, community-managed value chains like community-supported agriculture.

As a “rule of thumb”, we think that it’s technically possible for each “layer” of Cicero’s triangle (I’m going to call it like this ?) — i.e. long tails, aggregators and infrastructures — to be in every evolutionary state, thought the most common situation surely sees long tails in the user context (personalized, relationship powered experiences), and aggregators covering most of the intermediate layers of enabling services and channels, bundling the infrastructural layer and hiding it from ecosystem’s line of sight.

Patterns of Platformization, Gameplays and your strategy in mobilizing an existing ecosystem

Libraries of patterns of platformization are starting to abound: our includes twelve, Leading Edge Forum just published its Liberating Platform Organization report (restricted to members) that mentions circa 30, I’m sure others will follow suit.

Despite trying to understand recurring gameplays and patterns that one can use to shape an existing market in platform-like terms might seem complex, we think that this abundance of patterns can be reconducted to few essential typical evolutions from a Value Chain’s point of view.

We’ll continue to build on the initial insights shared on the last post, where Chris’ brilliantly nudged us with the idea that an essential trait of platformization is that of “transaction standardization”. We’ll try to identify what are these other typical evolutions and how they map with our pattern library. As a complementary step, we’ll explain how to engage in a fully aware process, starting from the ecosystem scan — with the aim of tracking existing ecosystem experiences (and behaviors) — then value chain mapping the emerging contexts to identify how aggregations strategies can play out, using these major set of evolutions.

As the first step in our analysis let’s look to the picture 2 below. Here’s an ultra-simplified picture of an “industrial” firm’s value chain. Normally, these firms provide solutions (as products, services or utilities) to a massified and replicable customer need (on the right of the evolutionary line, not by chance, as it needs to be an universal problem).

They do that by leveraging on distribution channels that are specific (and often out of the firm’s control, e.g. large-scale retail trade, or telco carriers for digital services). Sometimes these firms manage the purchasing directly (other times distributors do that, depending on the type and evolution of goods or services sold), and provides customer warranty, all this being based on a proprietary business process, that organizes suppliers and resources. This is normally the “nature of the firm” in value chain terms, as Taylor would have described in the XXth century.

It’s C-shaped:

Picture 2 — a “typical” industrial value chain map — it’s C shaped

The evolution of the digital market, mainly driven by:

- digitization of goods and distribution channels;

- increasingly pervasive technologies and rising potential at the edge;

- pervasive connectivity (everyone is connected to each other);

makes some evolution/gameplays/moves applicable to most markets.

These markets are subject to the trends of aggregation that are described in Cicero’s triangle (and in this post): long-tail markets fragment (as producers become more capable and independent), network effects become dominant and scale characterizes infrastructures, making aggregators and infrastructure grow huge and often monopolize their niche.

But how can we track these evolutions on the value chain map?

If you look to the picture below, we highlight the four main “movements”.

First of all, as Chris spotted two weeks ago, transaction handling and service purchasing “standardizes”: in parallel, consumers expect more personal and interacting relationships (humanized) with providers, that at the same time, empowered by technology and aggregation, move away from being treated as part of the “infrastructure” and travel to the top of the value chain. At that point, providers as well expect personalized experiences, and the possibility to express their full potential.

This transition is what we could identify as the evolution from “customer experience” to “ecosystem experience”.

By standardizing transactions, aggregators create network effects and make it easier for producers and consumers find the right “half of the apple”.

At the same time, the importance of mass distribution plummets — as it becomes more important to find the “right” producers — and customer warranty is superseded by verified identities, reputation and trust management.

As much as possible of a business process (supporting the creation of value) is consolidated and modeled in Software as a Service that contributes to empowering further the talented, passionate providers.

Picture 3 — the forces of platformization, plotted on the C-shaped industrial value chain map

A recurring Z-Shaped Value Chain

What happens then? We see a consolidation of shape in the value chain of modern markets, powered by modular infrastructures and organized by aggregators. As you can see below, these value chains tend to acquire a Z shape and actually all fits nicely with our new, S-shaped, aggregators’ zone.

Aggregators, in this context, will control mainly these elements of the experience:

- the transaction handling, to be able to embrace transaction-based business models, and to measure interaction and “sense” the ecosystem — as in Wardley’s future sensing engine;

- the context-specific SaaS, as a strategic MOAT, providing enormous value to now independent providers);

- reputation and identity, as strategic MOATs as “vetting” and policing will remain a main element of control on the ecosystem, and it will always be very complicated to exit a proprietary ecosystem if identity and reputation are not portable.

On a longer term, we can already spot the frictions that the identity and reputation moat creates: it’s not impossible to think these two elements of the value chain will eventually move into an infrastructural layer, thought this gameplay has been played widely in the past (e.g.: by companies like traity and jolocom) with no success.

Picture 4 — a “typical” aggregated (platformized) value chain map — it’s Z-shaped

Picture 5 — the aggregator control zone, in the Z-shaped value chain of platformized industries

Mapping Platformization Patterns

If we now take our pattern library of 12 patterns of platformization, it’s extremely interesting to see how these patterns play out in the context that we just described. These patterns are varied and therefore will be more interesting to reflect on how they fit into the picture, more than digging on the details. Let’s check them quickly.

Patterns:

- E3: Enable Personalization with Independent Providers

- E4: Create a new Profession

- E6: Stop focusing on Consumer

all speak about the key platform gameplay: moving producers out of the “infrastructure” layer, beyond the traditional customer “Line of Sight”, and accepting they don’t need to be intermediated by employees in representing the platform-org brand if they’re empowered enough.

Pattern E9 — Aggregating shared infrastructure and E10 — Unbundling assets are expressions of E1 — Reduce Barriers to the Market, and essentially relate to the capability that platforms have to encapsulate enabling “bricks” (e.g.: payment services, real estate, etc…) into low or no cost tools (eg: SaaS but not only) or support services, effectively making it easier for who’s talented in a certain context, to jump on the market with ease.

Pattern E11 — Generating Network Effects by connecting Niches essentially gets embodied by the standardization of transaction: by making a transaction standardized — and a the same time allowing a decent amount of “disobedience” to allow a certain degree of adaptation — niches of a market will “coalesce” around the platform strategy.

Pattern E12 — Transform competitors into Providers, can be related to the new position that the providers (former “suppliers”) have in the value chain. One existing supplier of an industrial incumbent could well play a platformization strategy as she knows very well — as an insider — both the provider’s expectations (e.g.: shortcomings of current experiences), as well as the interface of the industrial business process with the providers itself.

Finally, pattern E8 — Let the bet Emerge is clearly related to standardized identities and reputation management: platforms have born around the idea to leverage “operational” reputation gained in real interactions, in this way, the best in the market can always emerge.

Patterns E1 — Think Boundaryless and E7 — Climb the Value chain are more widely applicable and general patterns that apply to platform thinking as a whole.

If we look at the entirety of the patterns, surely two recurring situations can be identified to describe to the rise of independent producers (that may not be an individual, but surely a smaller and smaller entity — like SMBs).

Either:

- Small entities (eg: independent professionals or SMBs) are currently hidden by industrial incumbents as third-party suppliers, but their increasing potential — driven by pervasive technology and accessible knowledge — is making them more important than the organizing firm, in creating customer experiences, therefore calling for moving them on top of the value chain;

- Small entities (eg: independent professionals or SMBs) are already playing as a visible productive force on a given market, but they’re struggling to thrive and grow due to complex transaction handling, lack of well-designed support services, costly access to infrastructure.

In both cases, platformization strategies are essential to growth.

Picture 6 — the patterns of platformization at work on the Z-shaped value chain

Connecting all with Ecosystem Scan and horizon scanning

As the loyal reader might know, we recently updated a landmark post on our blog, dedicated to ecosystem scanning. As one of our platform design principles states (probably the most important one, the number 2), when one designs a platform strategy, she needs to Design For Emergence — putting a lot of care in understanding what behaviors and experiences are already characterizing the reference ecosystem.

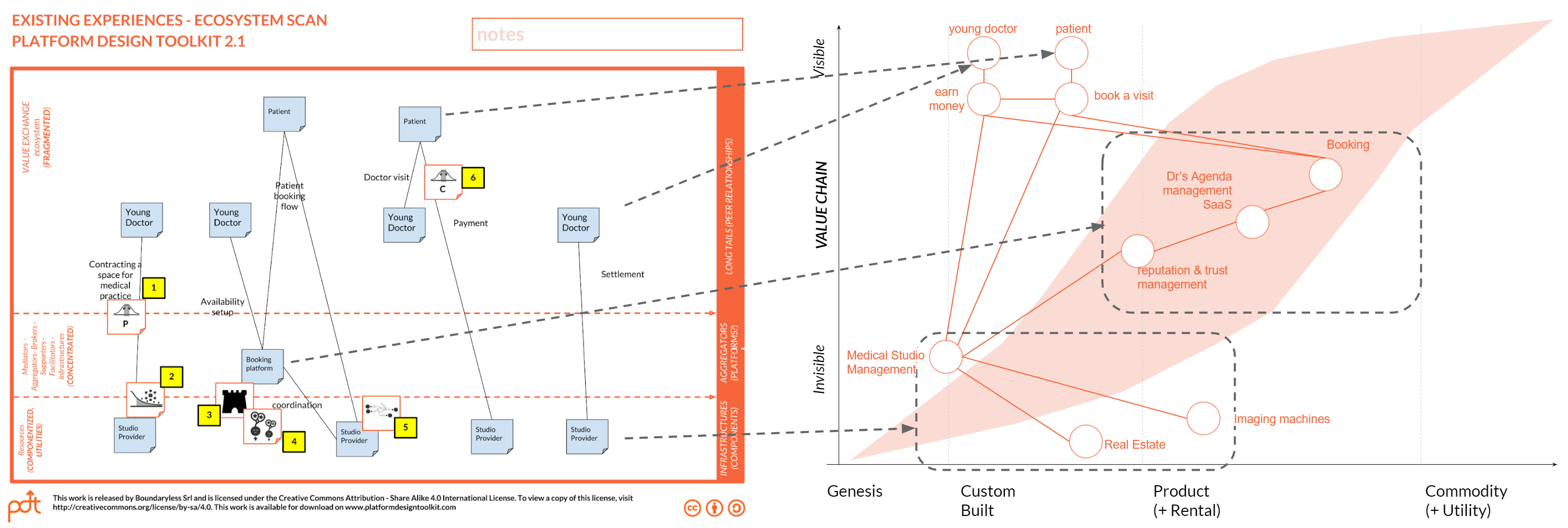

As s platform designer’s first step is always a good idea to sample all the experiences that are currently available in the target ecosystems: to accurately do this, we’ve created an advanced canvas of our Platform Design Toolkit called the Ecosystem Scan (on the left).

This tool helps you sample all this information, according to the three key layers (Long Tails, Aggregators/Platforms and Infrastructures).

The following ideal step is that of transferring the insights captured with the Ecosystem Scan, into a value chain map. This will boil down to:

- identifying what are the producers and consumers playing in the niche market, having long-tail expectations;

- identifying all the components that already are aggregated — or can be — as well as any incorrect positioning and evolutionary friction;

- position all spotted patterns in the map.

If we pick the example we’ve in the ecosystem’s scan presentation post here, regarding the current ecosystem of young doctors (applicable to medical specialists in general), and patients booking visits, it’s quite straightforward to see how we can first move the elements we mapped in the Ecosystem Scan, into a preliminary value chain:

While doing the translation, it’s also a good idea to expand a bit the sub-elements making up the entities mapped in the scan:

- the booking platform (e.g. doctify) can be seen as a stack of a booking system, an agenda management software, and a reputation and trust management system;

- the studio providers can be seen as bundling studio management (eg: check-in/check-out, invoicing/payment), real estate and imaging solutions.

It’s important to notice how, despite the studio provider is clearly mapped as an enabling infrastructure in the ecosystem scan, while unbundling it into components we need to acknowledge that, normally, pure studio management is provided by players in the long tail (SMBs, owning a studio) that leverage on a custom built real estate: every studio provider has to approach the business case, buy/rent real estate, design the interior of the studio, make the renovations, equip it, and eventually buy or rent imaging machines accordingly.

Below, we highlight the easy-to-spot frictions:

- [1] a scarcely evolved infrastructural element is clearly slowing down the evolutionary potential of this market network;

- the necessity to actively custom-build another element of the chain, real estate [2] is another clear friction;

Picture 8 — friction points in the current value chain, potential levers of platformization

Let’s look now at the platformization patterns that we previously spotted in the Ecosystem Scan exercise:

- E1 — REDUCE BARRIERS TO THE MARKET (number 1 and 6 in picture 7): It’s calling for cost reduction on both patient and doctor’s side, and this can likely be generated by massive standardization of the infrastructural layer (evolution of Medical Studio Management);

- E9 — AGGREGATING SHARED INFRASTRUCTURE (number 2 in picture 7): it’s calling for an aggregation of existing medical studio and imaging assets, with a reduction of idle time, therefore generating better returns on assets (indirectly generating E1);

- E8 — LET THE BEST EMERGE + E11 — GENERATE NETWORK EFFECTS BY CONNECTING NICHES): are calling for an aggregated market where it’s easier to find the right specialist at the right time, and in the right geography (other “half of the apple”), radically reducing the friction of dealing with different studio providers, different patient data tracking systems and more.

A transformed landscape according to these patterns might look like in picture 9 (below):

- the real estate owner, existing medical studio owner (let’s call it “OWN” for the sake of simplicity) shall be considered as a player in the long tail (out of the cost-infrastructure) to whom the aggregator will provide support services and aggregated demand;

- furnishing, renovating and equipping a studio might be provided as an aggregator service to OWN to ease onboarding and create a long-term commitment (eg: by long-term loan financing);

- OWN then needs to embrace a shared studio management software/process that will reduce the cost of management (eg: automation of invoicing, booking, common cleaning services,..) also indirectly effecting on pattern E1 (reducing barriers through cost reduction).

Pattern E8 + E11, would mainly operate through shared booking system, reputation and a more comprehensive SaaS offered to medical professionals, leveraging more patient data, providing features that would go beyond booking management. Patter E1/E9 would operate of course also through providing access to imaging at a likely lower rate, justified by centralized contracting and scale (an imaging provided would bid to become a partner of such a network).

The last thing to be noted, it’s the presence of current moats — existing booking platforms that currently provide doctors with aggregated demand.

A new entrant on this industry, that would like to execute this strategy, would need to consider existing aggregators, on the other hand, an existing aggregators might consider this strategy as a potential strategic evolution.

Picture 9 — a platformized landscape

Based on these initial hypothesis the platform designer will be able to use the tools in the toolkit, starting from the Ecosystem map and Entity portraits, following the process detailed in our User Guide.

The analysis in the value chain contributes indeed at least in adding two new entities to the map, beyond the obvious, owners of existing medical studios, and simple real estate owners that could consume the onboarding services — if conditions are met — by self funding their network onboarding (transforming real estate into a medical studio), thus radically reducing the investment needed for the platform to grow in new locations.

Conclusions & Take Aways

Wardley’s Value chain maps have been amongst the most radical innovation in strategy of the last 20 years. We think that adding these maps to our platform design practice will improve radically your capability to design aware strategies that can fit with an increasingly complex reality.