Ecosystem-Driven Organizations: Shared Market Maps, Forcing Functions and Investing into Small Units.

What does it mean to adopt an Ecosystem-Driven organizational model that can grow organically by validating products and being driven by the market? At Boudnaryless we adopt and promote a “hourglass“ structure connecting Exploration with Investing

Simone Cicero

Abstract

What does it mean to adopt an Ecosystem-Driven organizational model in an effort to create an organization that can grow organically by validating products and being driven by the market? How can one use strategic insights in a way to avoid the creation of structures that can easily become sclerotic once the market conditions change or other environmental factors evolve?

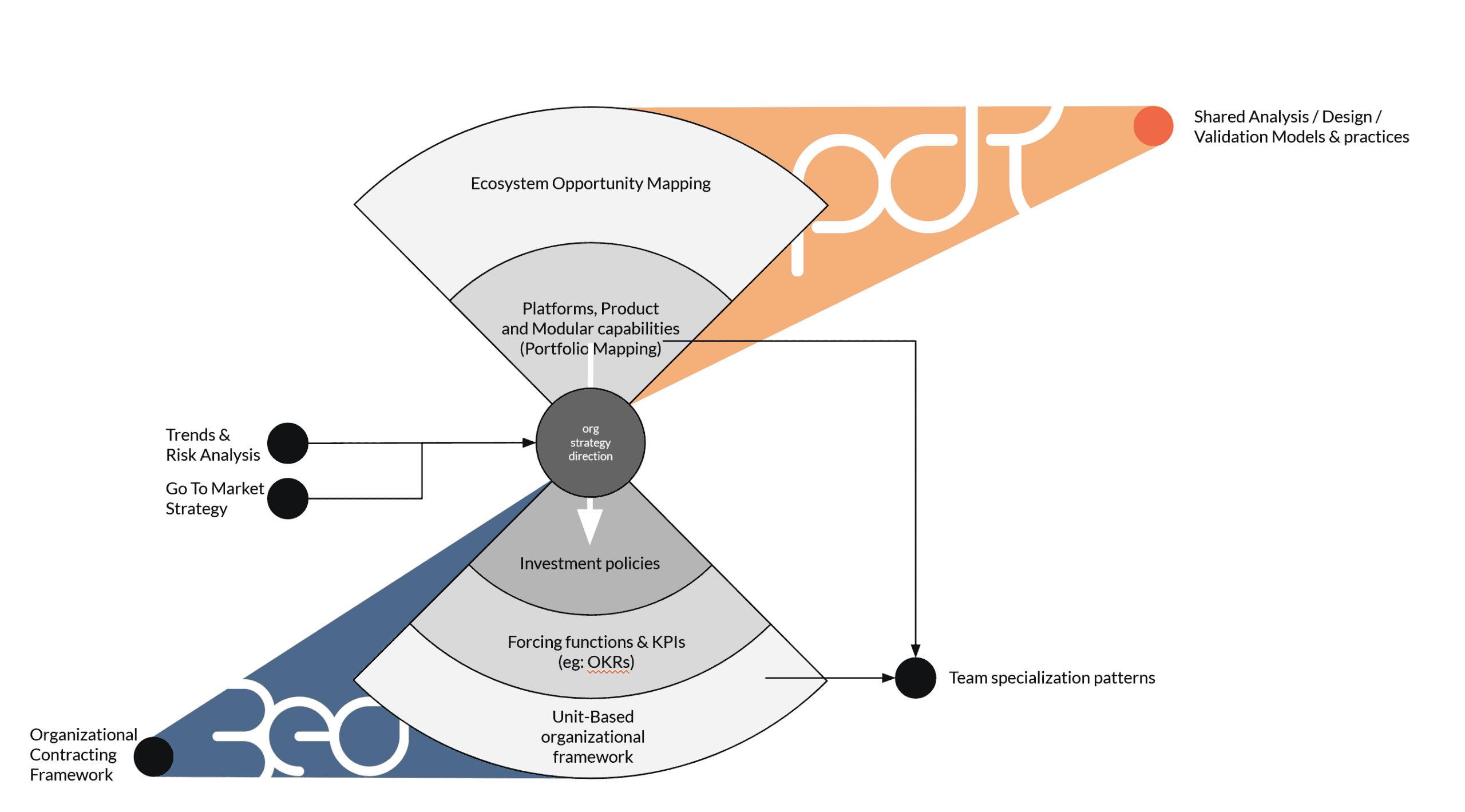

At Boudnaryless we adopt a sort of “hourglass“ structure, driven by a solid approach to ecosystem mapping and opportunity identification that consolidates into a portfolio view of products, and other modular elements. Such an understanding of the ecosystem feeds into a strategic process that – informed by other external factors – nudges the organizational development through investments, and, even more importantly, through a set of enabling constraints, such forcing functions and contract types, that facilitate inter-unit collaborations. Let’s see how it works.

Subscribe to our newsletter if you don’t want to miss a thing!

How should an ecosystemic organization be set?

In the last decade, we witnessed the application of a theory or organizing that has been largely inside-out, and often based on product and service with a stable, scalable, and predictable value proposition.

We achieved the possibility of organizing inside-out with relatively low-risk thanks to the fact that the world we used to confront with our organization was in itself stable, subject to relatively long-term cycles. We’d probably have to better say that the world itself wasn’t stable at all but – instead – but our image of the world was. In reality, a massive amount of externalities generated by the industrial ways of organizing we have been adopting has accumulated and contributed to speeding up and putting in motion a set of processes that have driven the reckoning with complexity we’re living these very days.

Two years ago, in September of 2020, recognizing the complex turn we’re subject to, we wrote on this blog how:

“On top of political reasons, market fragmentation will also result from a growing set of unfolding risk factors due to the exponential social interconnectivity we’ve been living in, through the last 20 years of globalization: a dynamic that is now generating a bounce back to social production systems characterized by lower interconnectivity.

[…] a decentralization of economic structures and social systems (markets, supply chains, civic institutions) is one of the means of winding down the possibly calamitous, cascading risks we are increasingly exposed to, due to global interconnectedness of the human techno-sphere.”

From “Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Enabling Organizations rhyme with 21C Complexity”

On top of this I like to quote a podcast interview we had – still more than 2 years ago – with a the french analyst and always attentive observation of the present Nicolas Colin:

“if you come back to the nature of today’s economy, an economy that’s driven by computing and networks, the law that you need to keep in mind […] is the following. There’s now more power outside than inside organisations. That’s the key to understand everything. It explains the weakening of traditional top down command and control, bureaucratic organisations”

From: “The Entrepreneurial Age: Networks and a fragmenting world — with Nicolas Colin”

What are thus the lessons that we’ve to incorporate into our ways of organizing at the onset of the 21st century?

Two major elements emerge as decisive to incorporate: first, the need to completely revert the inside-out approach into a decisively outside-in approach. In this setting, the strategy and the shape of the organization are dictated by what happens outside of it, in markets that are extremely more dynamic and complex, and in a societal context that shifts more strongly and in faster cycles. Secondly, the need to make the inner workings of our organizations much more fluid and capable – on one hand- to be more easily reorganized, and on the other to do so in an autonomous and effective manner with little or no top-down guidance.

Outside in: mapping ecosystem as the driving shaping force

Adopting an outside-in perspective to organizing cannot prescind from understanding the roles of ecosystems. In our practice we believe that two major elements are needed to adopt such an outside-in perspective: the practice of mapping ecosystems, by breaking them down into arenas, of which one can build value chain abstractions (a practice that we described recently in our recent post “Framing a Portfolio of Platform-Ecosystem strategies inside an Organization”) and the mirroring practice of mapping all the elements of the portfolio that exist inside the organization and that can be re-bundled to respond to the opportunities that emerge.

What we normally do in this case is look into several types of assets that the organization owns. More specifically we are talking about:

- user-facing products and services;

- internal and external APIs and other modular and reconfigurable elements;

- key processes that are run by the organization and can constitute an isolable capability;

- other types of assets that can be modularized and integrated into new products.

By assessing the portfolio in such a way, the organization can easily achieve two key outcomes: an understanding of the existing gaps in the portfolio, and an assessment of opportunities for growth. The latter can be found in terms of synergies between products and services (for example in case two different products share a certain audience, handing towards an opportunity for integration or upselling), or even the reduction of overlaps – and thus waste of resources. Even more importantly, this approach can bring relevant clarity in terms of pointing out a need to integrate the portfolio by developing a lacking element, a module, or even a new customer-facing value proposition, given a platform-product opportunity has emerged from the analysis of the value chain related to a particular arena.

As the reader knows, at Boundaryless we have a solid practice for the identification of what we call a platform strategy model as a mix of three key value propositions (marketplaces, product bundles, “extension platforms”): a detailed description of the approach, in terms of understanding how such three value proposition interact systemically, can be in this post: “Value Propositions in Business Ecosystems – Products, Marketplaces, Extensions”). An as much solid approach also exists in our practice to analyze the information we capture from the environment – in the form of arenas and ecosystem scans – and, through the lenses of the application of Wardley Mapping and our library of Platform Plays for the extraction of a credible strategy; see: “Apply Value Chain Analysis with Wardley Maps to identify a Platform Opportunity”.

Coupled with a well-codified library of methods – designed to provide a common and comprehensive design language such as the ones in the Platform Design Toolkit – Boundarylerss Ecosystem Scanning and Portfolio mapping techniques provide organizations with three basic pillars of restructuring the organization in an outside-in way. Expect us to write more about our Portfolio management practices in the future, covering advanced elements such as the creation of shared playbooks, partners onboarding, and more: these are topics where we’re helping several organizations and, as always, we’ll isolate key learning and shared practices and make them open source for you to use.

How to help the organization unbundle and re-bundle around the emerging opportunities

Once the organization has achieved a systemic view of the opportunities existing in the ecosystem and, as a complementing set of information, how the current portfolio of products and other components map vs it (including gaps and overlaps), such information needs to be leveraged by the organization in dictating priorities. In our understanding of how a complex-friendly organization should work this doesn’t mean creating top-down functional structures and assigning tasks to people. On the contrary, in shaping the organization according to the insights coming from the outside-in analysis, we believe that the principles to be embraced are those of nudging, and of the creation of so-called “enabling constraints”.

It’s important to note that a certain amount of centralization organizational strategy may be needed for two main reasons: first, because strategy identification happens at the organizational level, for example, to drive the fulfillment of a certain purpose over a completely loosed and entropic execution). Furthermore, if the organization has to embrace the very portfolio-based point of view that we described above, it likely needs a preferred point of view on it, that is also able to detect overlaps, synergies, and potentially clashing interests. It’s certainly impossible to achieve such a view from the periphery of the organization and thus we’ve to accept that a certain team, or (better) a dynamic space or process – to which participation can be encouraged – has the responsibility to both, internalize the insights on the portfolio gaps, and cross such insights with key pieces of information arriving from the market and society. These signals could be for example the impacts that certain technological changes or other societal trends may have on the organization, its stakeholder, and its purpose.

The centralization of strategy is not a problem per se, but it may be if it introduces rigidity and top-down planning and it gets enacted through the wrong means.

In the organizational setting, we propose, the enactment of strategy in a complex organization is essentially developed through three major elements:

- investment policies needed to direct resources intelligently toward the elements that are the most strategically needed;

- forcing functions and other complexity-friendly and self-management-oriented mechanisms to nudge the organization in a certain direction;

- unit-based, loosely coupled organizational frameworks that are aimed at the reduction of bureaucratic overhead, and management effort, in favor of a more versatile, modular, and easily reorganizable organizational structure where interdependencies are reduced, generating a more fluid, and change-prone setting.

If the practice of Platform Design Toolkit is strong in providing teams a shared set of analysis, design, and validation methods, the 3EO instead provides the basis for the organization to look into how capabilities can be organized internally.

As the most loyal readers will know, the 3EO (Entrepreneurial, Ecosystem-Enabling Organization) suggested structure provides mainly two elements of archetypes for organizations to distill their own approach. First of all, it provides an organizational framework that is unit-based, designed around the idea of having micro-entrepreneurial teams supported by shared services. In the 3EO framework, such micro-entrepreneurial teams are, management-wise, seen a bit like black boxes that are able to self-manage as long as they perform well according to a set of forcing functions. In the original RenDanHeyi implementation – from which the 3EO gets most of its basis – the key forcing function is the positivity of the P&L, with units required to achieve business sustainability. In other contexts, such a forcing function could be integrated or rethought fully. Departing from only using positive P&L and introducing, instead, other elements such as trickling KPIs cascading from higher order nodes to lower order ones, will allow the organization to factor in more specialization and capability to plan, introducing though more rigidities.

We’ve experimented with adopters (and on our own) possible ways to achieve team specialization and optimization that is not just based on unbundling and optimizing for trading products & services at the interface. For example, we discovered it’s possible to map team structures to:

- products being built;

- key functions being played in relation to such products;

- particular legacy subsystems that enable the execution of products (eg: isolating a team running a particular legacy system, or a policy compliance team);

and more.

We tested – and we’re still testing – how the MEs (self-managed micro-entrepreneurial units) can adopt further specialization patterns. It’s certainly interesting to integrate the principles of RenDanHeyi and 3EO with existing and leading team structuring approaches such as those defined by SAFe, or Team Topologies (optimized for the pervasivity of DevOps) but also with approaches that are more proper of the product-led startup-scaleup realm, such as the ones described in “The Types of Product Team Organizational Structures” by Casey Winters. In product-led settings, according to Winters, one may have to consider organizing by Type of Product Work, by Customer (as modern products can really have several customers, such as providers, consumers, and developers…), or even by Value Proposition – which is probably the approach that is the most resonant with the roots of RenDanHeyi. More research is needed (and is coming from Boundaryless) at the intersection of the different approaches to team structuring.

Complementing – and influenced by – the approach to team structuring, the 3EO also provides another key element of organizing: i.e. a powerful way to address the relationship between the units inside the organization. It does with a contract-based, and promise-based manner where units interact in a continuous cycle of commitments and rewards.

Instead of having a typical 1-N (or at least n-N) way of organizing, with many little units relying on bigger units (top-down), the 3EO encourages a much more horizontal and peer-based way of organizing with key contract types. First, the VAM contracts (Value Adjustment Mechanisms contracts) transform the typical top-down management relationship between an upper node (for example a division), and a lower node (for example a certain business unit) into an investment contract. VAM contracts are normally defined between a certain organizational structure designed to nudge the execution of the strategy (can also be directly the board or even a strategic venture investing firm) to empower the smaller node through capital. The contract defines the unit’s objectives (can be a newly created unit or a unit negotiating its yearly objectives), the investment needed to achieve them, and the expectations of its members in terms of returns, access to shared revenues, or access to potential equity being created in the process of creating something new. On the other hand, EMC contracts (Ecosystem Micro Community contracts) allow units to agree between themselves into setting market-driven objectives emerging from collaborations, shared investments, and more.

Free and transparent access to the organization’s portfolio abstraction – we found – is key to allowing such an emergence: the information about the target ecosystem, the status of the product portfolio, and the strategic considerations need indeed to be made available to all players in the organization, encouraging the formation of new nodes and new collaborations, and potentially accessing capital more easily as newly minted initiatives may intentionally go to cover those “holes” in the portfolio of the organization as identified by the strategy-setting team or process.

Conclusions

Rethinking your organization in a way that is more conducive to success in a complex landscape goes through two major changes: first, approaching ecosystems more intentionally, learning how to break information down, and analyzing the opportunities to develop product and service strategies. Secondly, breaking down the organization into small teams, give them transparent access to market and portfolio analysis and empower them through standard contracts and easily available incubation capital. Despite such a perspective that could be seen only within reach of larger organizations, in our experience, this is something you want to start as soon as possible, as soon as one product consolidates and you’ve to move away from a single-product organization into one that runs multiple value propositions.

Do you want to learn how to frame your product to resonate with your Ecosystem? Learn how to design platform strategies with us at the Platform Design Bootcamp coming up in October

Join us at the upcoming Platform Design Bootcamp: