Framing a Portfolio of Platform-Ecosystem strategies inside an Organization

How can an organization successfully map multiple markets and coordinate product-platform strategies so as to optimize resources, reduce double spending, and increase chances of success? Here’s Boundaryless approach to portfolio innovation

Simone Cicero

Luca Ruggeri

Abstract

In this installment of the Platform-Ecosystem Atlas series, we will explore how an organization should develop a shared representation of the target market-ecosystems towards which it aims to address platform strategies. We will also see how to connect such representation with several Platform Strategy Models envisioned through value chain analysis.

We’ll investigate how Arenas breakdowns can offer a reliable way to create clear and org-wide shareable information boards to help teams avoid double mapping their market context, and how developing a strategic portfolio view can provide relevant opportunities for effort optimization and increase market success chances. In the end, we will also peek into the action-research as we’re currently doing it with our customers and adopters, with regards to how 3EO powered organizational models can provide a powerful way to align your organization with market dynamics, improving team autonomy and accountability, and enabling new team incubation; and the possibility for the organization to plug itself into the market at various layers and to let third parties do the same, nicely plugging into the organization’s products and services.

Subscribe to our newsletter if you don’t want to miss a thing!

How to approach the evaluation and pursuit of multiple opportunities for platform innovation, in a complex organization that has the capability to do so?

That’s a recurring question when you happen to work in large organizations that are characterized by:

- the need to innovate “systemically” and look for new business cores to be developed in pursuing diversification or ambidextrous innovation strategies to do both exploitation and exploration;

- a relevant number of internal capabilities and assets that should be combined and developed to generate more value;

- a lot of potential value that is still to be unlocked in the employees (or more generally contributors, and work ecosystem) potential.

At Boundaryless we’ve been faced with this challenge multiple times – especially when working with large groups, both in for-profit and no-profit – and we developed a structured and consistent approach to innovation portfolio management that we want to preliminarily share in a structured way with our adopters today.

In a blogpost from almost a year ago that describes the three key challenges that organizations face as they aim at becoming platform-ready we highlighted three lines of activity:

- unbundling the organizational capabilities, transforming them into modules, and making them easy to re-bundle;

- to instill platform thinking literacy in the teams;

- to help the organization re-bundle around market signals through entrepreneurship.

After a few years it has become clear that building a live, visual, shared representation of a portfolio can effectively support the organization in doing 1 (unbundling) and 3 (re-bundling) despite, obviously, a portfolio breakdown doesn’t fully enable the organization per se if not accompanied by other key activities such as upskilling the workforce (as in point 2), building an entrepreneurial culture and adopting an organizational model that is conducive to achieving such result, mainly by creating the right set of incentives and an incubation process – or more generally and probably less top-down – an incubation setting.

Learning how to construct a portfolio view of:

- what are the opportunity spaces (as ecosystems) the organization is active within;

- what are the characteristics of the players that make up the ecosystem;

- what are the capabilities that the organization has internally, and what their interfaces are;

- how those capabilities are currently organized as products/value propositions, what’s the growth thesis of such products, their validation stage, etc…;

- what are the common layers, and technological stacks that serve multiple value propositions;

provides an organization with a massive innovation capability advantage.

Why is that? Such a portfolio view helps the organization act strategically, identifying opportunities to pursue and connect the dots, being able to leverage a shared space of information and insights across products and teams, intentionally driving growth across products (by leveraging pockets of growth that are present in certain products and spilling them over to new ones), solve strategic frictions between products (e.g. when one product has the potential of enabling a richer business model by being commoditized, etc…)

How do you construct a Portfolio view?

In our experience, a portfolio view must have two essential elements. It needs to start from an outside-in characterization and a shared representation of the market-ecosystem. It’s important that this representation starts from mapping information from the ecosystem, therefore characterizing spaces of opportunities that exist beyond the single organizational footprint. On the other side, the portfolio view obviously needs to feature the organization’s products and capabilities.

It’s rather common to see organizations developing a portfolio view starting from their products while the correct approach – we’ve found – should always be that of starting from mapping ecosystems. The reason is fairly intuitive: similarly to how you don’t start from the solution when thinking about building products – instead you normally start from the problem that the customer is experiencing – similarly, articulating a proper complex and systemic platform strategy has to start from the ecosystem, the systemic interactions between the players and what are the expected outcomes that involved players have.

Side 1. Mapping our target Ecosystems

As the reader may be familiar with, in the (almost 10) years since the first release of the Platform Design Toolkit we have adopted several methods to map ecosystem entities, assess their needs and potential.

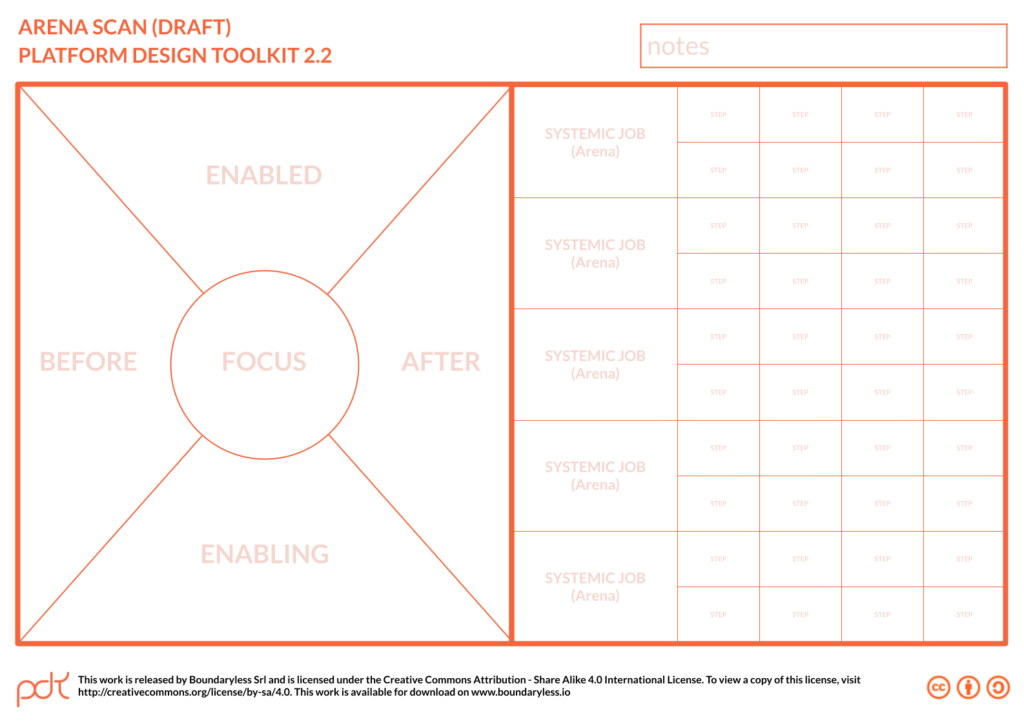

When working with single-project focused teams we quite recently started to adopt a so-called arena scanning technique (introduced here and integrated here) that will also soon be integrated into the Platform Opportunity Exploration Guide in an upcoming updated release.

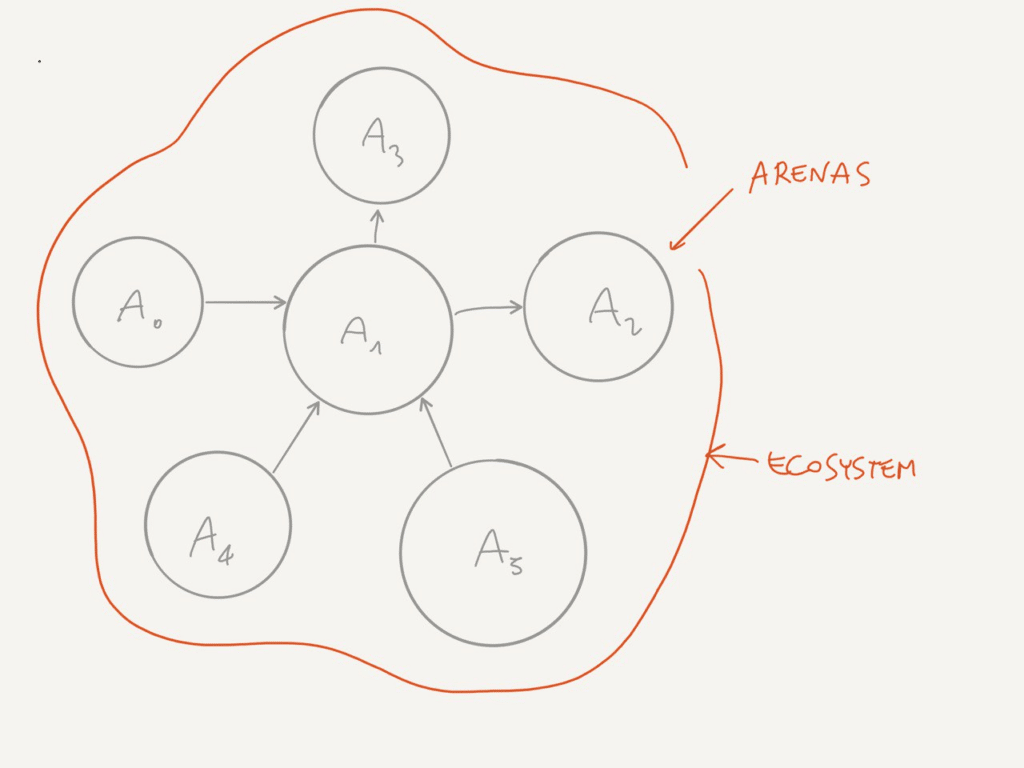

As a quick reminder: we consider arenas as “Systemic Jobs To Be Done”, thus systems of interactions between entities that can be seen as “sub-parts” of a broader “ecosystem” or space.

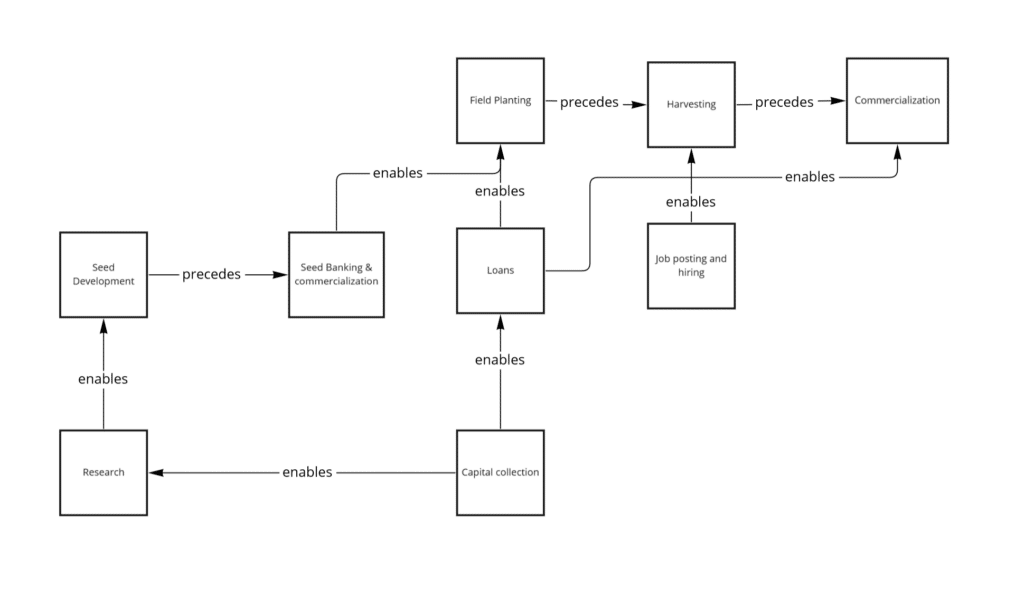

You can think for example of an arena as “Field Planting” as a sub-part of the broader ecosystem of industrial agriculture.

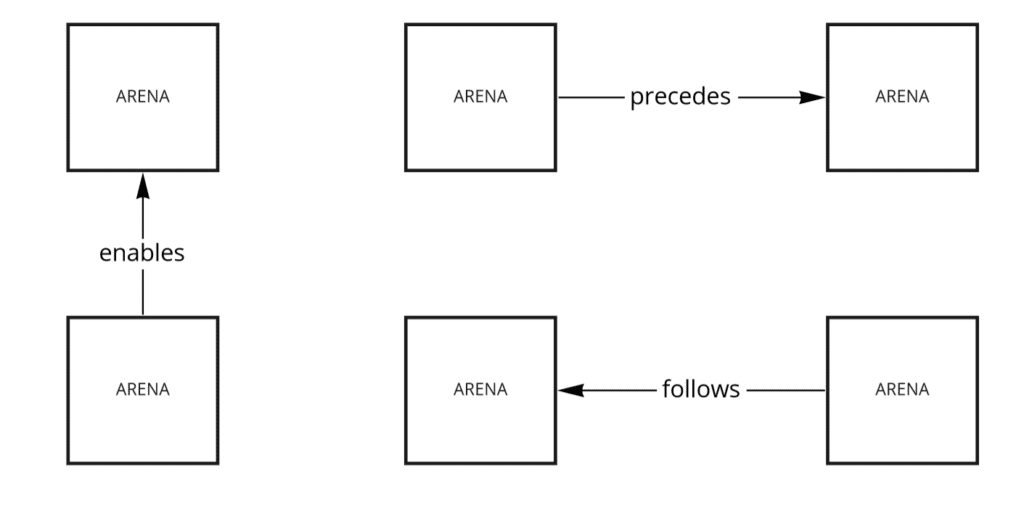

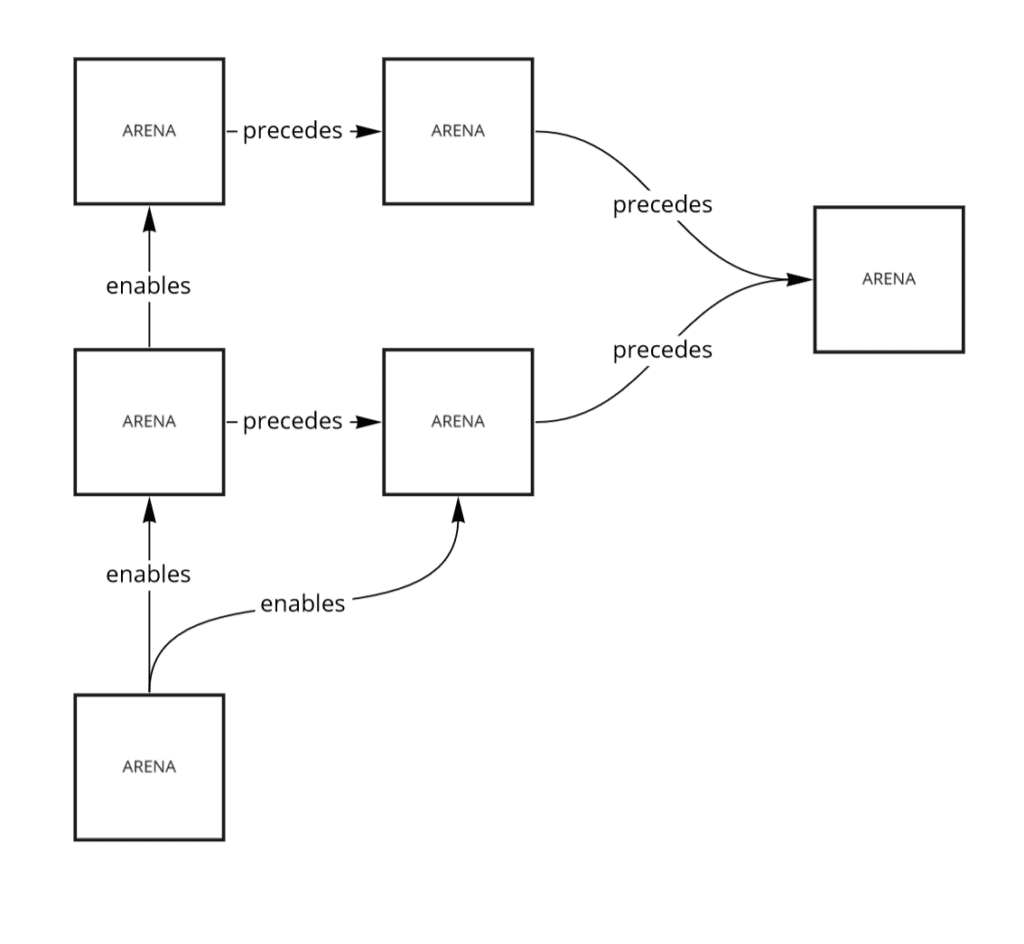

When working with single-project focused teams we use arena scans taking a team’s perspective and then construct a map of arenas that, with respect to the core focus arena, are in a relationship of either preceding or following, enabling or being enabled (see below an extract of the arena scan):

When working at organization/portfolio level we thus integrate the view of multiple teams and generally construct a “continous” arena space that can be shared across the organization. Below you can see how we represent relationships between arenas, and in the picture that is following, even how a typical ecosystem representation, that involves many arenas, will present itself (abstractly):

To give a more tangible idea of the kind of situation you could face as you complete an ecosystem representation through the arena abstraction, remaining in the context of industrial agriculture you can imagine something like this:

As the reader can see – once you remove the team’s focus – such a representation of the ecosystem can well be considered abstracted from the organization involved in the mapping. That’s certainly true albeit any mapping activity is always to be seen as embedding a certain “perspective” and assumes a particular value when contextualized in the eye of the mapper.

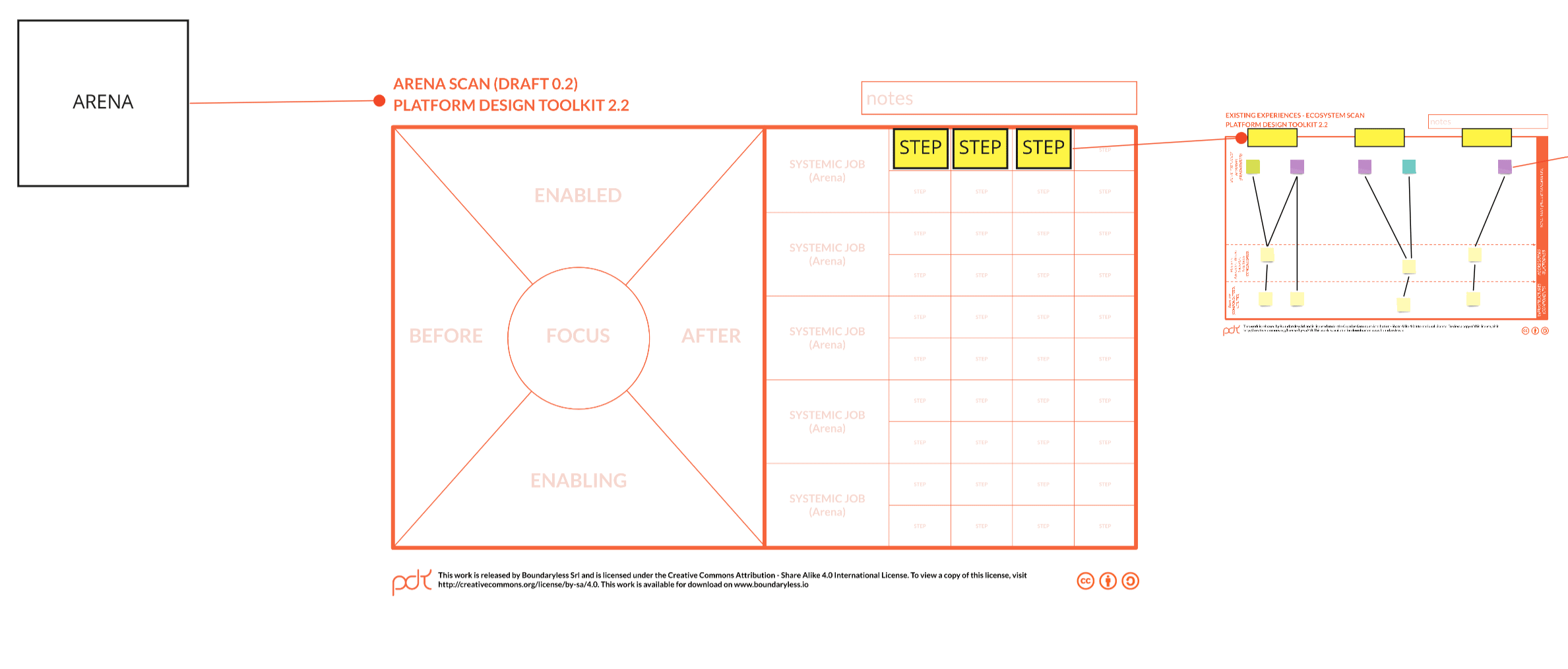

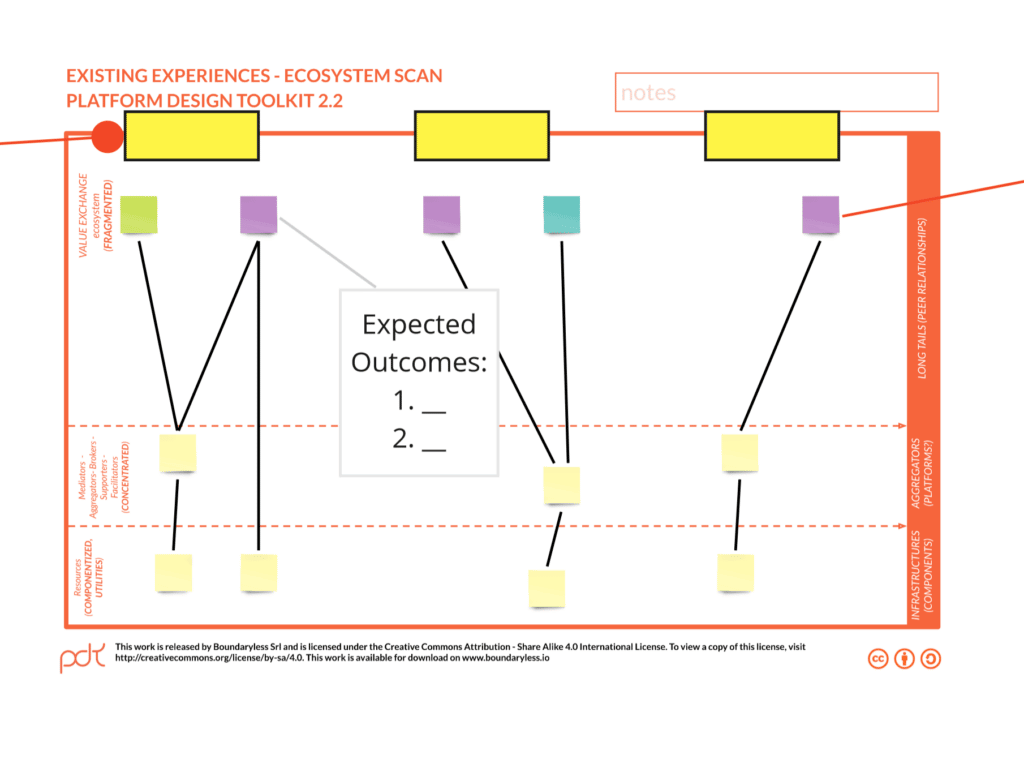

On top of the representation of the arenas, we then perform a deeper analysis of what happens inside each arena. We use our Ecosystem Scan canvases: as the loyal reader may recall, we recently explained how we are also using ODI to look into arena-ecosystem scanning but as a general rule of thumb you can imagine that each arena will be broken down to several sub-arena steps and each of those steps will be informally scanned through the Ecosystem Scan’s three layers. As a reminder, such a technique helps adopters map:

- what entities are involved in the niche exchanges;

- how such exchanges are mediated and;

- what resources are used in the process.

Inside each arena, a variable number of steps can be identified and described.

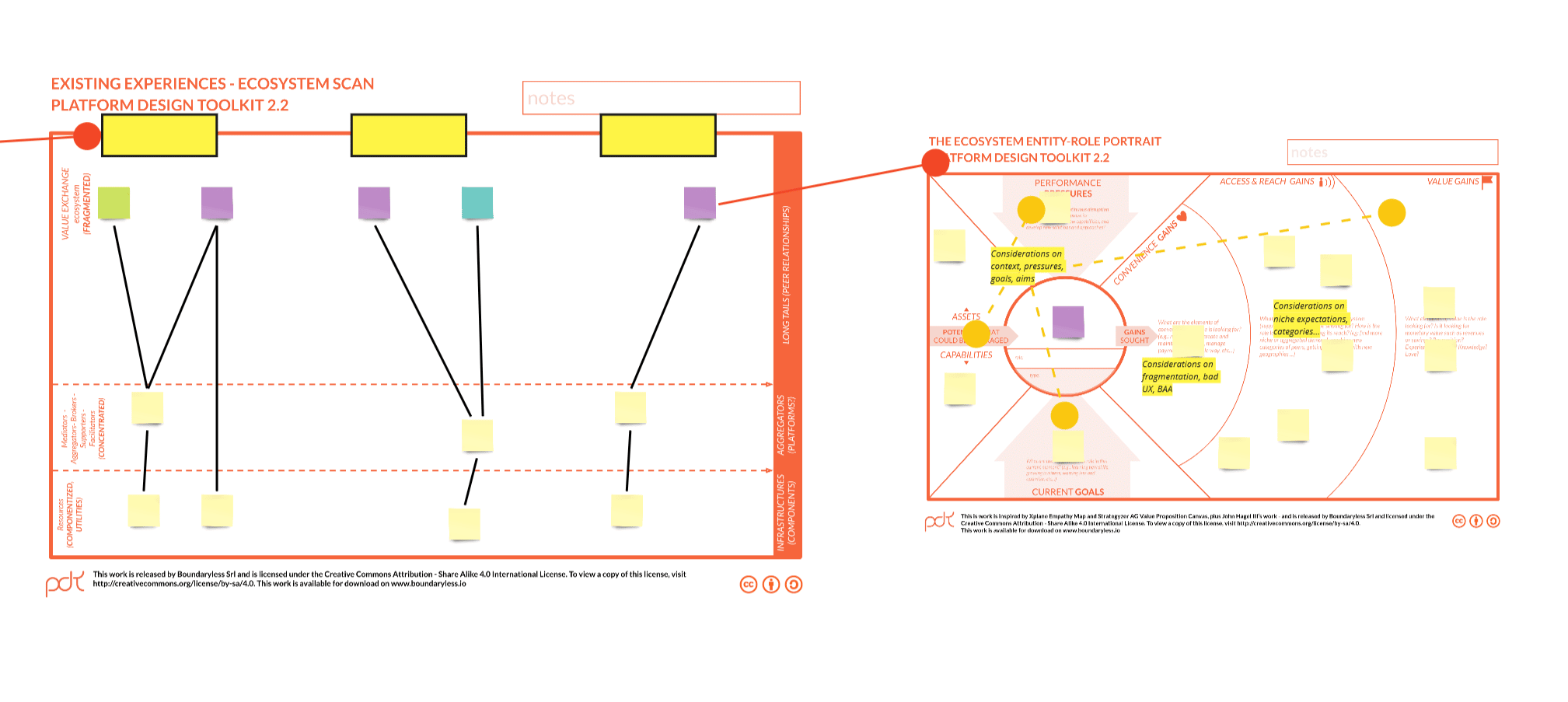

Once at this point, one can enrich those maps by including additional elements that can help characterize how the ecosystem entities are – at the moment – engaging with the context.

Further characterization of the ecosystem’s arenas

One thing we normally do is to redact the first iteration of our entity portraits first released in 2017.

The entity portrait can be seen as a sort of derivative of a mix of a Value Proposition Canvas and an Empathy Map. Drawing an entity portrait of all the entities that emerge from the scans – across the board – will give you a sort of inventory of all the entity-types you’ll be in touch with as an organization as you reach out to the market-ecosystem for commercializing your value propositions.

In our experience, a well-redacted library of entity portraits gives the organization a shared understanding of who is the organization talking to and interacting with, and provides a substantially important element for the articulation of any platform strategy:

- first, it gives you information on the general entity context: the pressures they’re subject to, their goals and values;

- secondly, it gives you information about what type of niche seeking dynamics are in place and this information will be heavily important as you’ll ask what are the “canonical units”(a) in which you’ll have to seek “liquidity” in the strategy launch phase;

- third, it gives you information about the existing alternative: as you map the convenience gains that the user is looking for, you can indeed describe the level of fragmentation the user is experiencing and the best available alternative (eg: having to use multiple products that don’t speak to each other)

(a) NOTE: a canonical unit represents how categories such as geography meet with product/service type categories in marketplaces. In launching marketplaces is indeed essential to understand how users search for “a plumber” (P/S category) in “New York” (geographic niche unit), or a “single room” (P/S category) in “Paris” (geographic niche unit), or a “black car” (P/S category) that can pick me up in 5 minutes (geographic – distance/time dictated – niche unit). The concept was popularized by Dan Hockenmeier as he spoke about it in this seminal conversation at Venture Stories

A way to enrich further the information about the as-is ecosystem (before your product strategy is enacted) will be that of collecting what are the expected outcomes that all the entities have as they are involved in the execution of the single step of the systemic job (arena).

Why is this important? Mapping expected outcomes and connecting them with the context where we want to articulate a product strategy is helpful if we have the resources to perform systematic research (for example through massive surveys or other validation techniques) to fully understand how players involved in the space at the moment are either underserved or overserved and. As we explained on our previous piece on Adopting Outcome Driven Innovation and the Jobs to be Done framework within Platform Design this information can be crucial to understanding how the platform strategy we want to bring to the market resonates with such expectations, for example by:

- charging less an overserved customer that has to deal with a plethora of costly tools or;

- get the job done better for an underserved customer that needs, for example, demand generation and not only a SaaS solution to simplify her business process.

Side 2. Defining Product/Innovation strategies that resonate against the ecosystem

In the first part of the post, we explored how a portfolio view should start by cataloging information about the market, the ecosystem, and the currently available experiences. This is an essential part of your portfolio view because anything you’ll build will have to resonate against it.

What’s the next step then? The idea is to develop a multiplicity of what we call Platform Strategy Models (PSMs in short) which – in a few words – represents how you want to articulate the triplet of value proposition elements we recently described that normally compose a complex platform strategy: a product/service bundle, a set of marketplaces and an extension platform strategy (not always all present).

Developing such a PSM – starting from the information previously obtained about the market – normally goes through an intermediate step: analyzing the value chain.

We recently described in an extensive review in our piece: Apply Value Chain Analysis with Wardley Maps to identify a Platform Opportunity. The assumption here is that a rigorous value chain analysis (that takes the information mapped in the arena and ecosystem scans as an input) provides the designer with a strong and clear indication – given a certain opportunity space – of:

- what should be embedded in the product/service side (a product/service bundle normally aimed at the main producers of value in the market);

- the characteristics (potentially multiple) of the marketplace (connecting such core customers with either their own customers or suppliers);

- and a potential extension platform strategy (a way to use plug-ins, apps and more to extend the features of the core P/S bundle).

Developing the right sensibility to choose what and how much of the ecosystem information has been mapped shall be put into Wardley maps is a hard catch – we recently discussed with Ben Mosior about this – and we’re experimenting with new techniques to assess how arenas lend themselves to Value Chain Mapping. One easy approach would be choosing to build one Wardley Map for each arena and – following the first mappings – later evaluate how value chains overlap and integrate.

Value chain overlaps can also be spotted early on. Sometimes, arenas – or better the ecosystem scans you’ve obtained as the following step – lend themselves to be reorganized in more coherent sets (we briefly spoke about this in this post already shared above) because, for example, they tend to either present a strong process/workflow continuity (one doesn’t really make sense alone) or share a substantially identical set of entities.

In general, learning how to look into Wardley Maps more as a “process” that generates insights on your PSM, than as a precisely framed artifact that is supposed to tell you what to do in precise terms, should be the right mindset.

Once the preliminary elements of the PSMs have been framed as the triplet of Value Propositions (P/S bundle, marketplace, extensions), to really build a credible portfolio entry, one needs to complete it with:

- the related business models and pricing strategies (for example, a service bundle could be provided as a subscription-based SaaS while the marketplace side could be priced through a take rate);

- an abstraction of the network effect flywheels that will be responsible to drive value growth and create defensibility (scale, brand, lock in, tech advantage…);

- the go-to-market strategy (how to achieve liquidity and in what canonical units first, what side to focus on, growth tactics).

and potentially a description of the simplified domain model (entities, workflows…) that exists at the basis of the PSM.

Once we do this for many arenas and opportunity spaces – and especially if our strategies portfolio features many initiatives – we’ll end up with a complete overview of:

- the markets/ecosystems our company is addressing;

- how they are related to the PSMs we are prototyping, validating, and growing;

- what roles are possible for customers and partners on any of the PSMs and their overlaps;

- what domain models we use as a basis of the existing PSMs, and how they overlap;

- how certain components, units, and partners can play roles

Further Works: Team Structures, Open Protocols, and Organizations as Cities

It’s important to understand that having a portfolio view of an organization’s reference markets and ecosystem, and of the multiple PSMs (Platform Strategy Models) that the organization is actively bringing to the market can be very helpful in many things such as:

- increase shared understanding of market penetration and strategy across teams;

- ensure broader coordination across products exists;

- ensure strategic growth can be achieved across products by intentionally spilling over user pockets;

- ensure key assets can be used across different products maximizing their use and impact;

- onboard customers and, most of all, partners in the right way, multiplying the value that the organization can provide to them (imagine for example onboarding third-party service providers once, and let them deliver value across multiple products that provide a role for them);

But it doesn’t solve all problems.

More specifically work needs to be done to ensure teams, units, and divisions (if any) are correctly empowered, accountable, and connected, that OKRs (or alternative performance setting processes) are in place and that the organization organically moves through continuous market exploration and validation: the risk otherwise is to end up in a bureaucratic nightmare.

Lots of interesting work has been done recently in mapping organizational models and team structures to products and product elements (such as the components of a portfolio view). Here on this blog we often talked about how a common protocol of organizing is emerging and – most specifically – we made parallels between:

- Team Topologies suggested four fundamental topologies (Stream-aligned teams, Enabling Teams, Complicated Subsystem Teams, Platform Teams);

- Rendanheyi’s/3EO key artifacts (Micro Enterprise, Ecosystem Micro Community…);

- Amazon’s Two Pizza rule and API mandate ;

- Spotify Model or SAFe (Scaled Agile Framework);

and others market-oriented (vs functional or matrix-oriented) ways of organizing.

Overall, our objective as organizational developers looking to adopt organizational structures that are conducive to maintaining and evolving a modern portfolio of (platform) strategies, needs to be aimed at:

- increasing teams’ autonomy and accountability in evolving a particular piece of the portfolio;

- increasing the chance (for example through team incubation techniques and services) that new teams can form inside the organization to extend and integrate the portfolio in a nice integration with other team’s work and existing products in the portfolio;

- increasing the chances that external partners can either plug into “our” system of value propositions or that our products can be used as components – in complement with others – to build more complex user-oriented scenarios.

Achieving an organizational setting that can coherently and naturally deliver an, ever-growing and ever evolving, product portfolio can be a decisive advantage for organizations.

In an attempt to reduce the amount of intentional design that needs do be done top down in structuring these teams our 3EO Framework promotes – among other things – the adoption of distributed Profit and Loss. Using positive P&L as a forcing function, as a product-team boundary (in reality a product may include several teams), can dramatically reduce overhead and, if coupled with enforcement of programmable interfaces at the team-product boundary, can help optimize the organization for fast flow.

New trends such as those behind Web3 and blockchain are even pushing further the way we think about the boundary between an organization and the market, effectively challenging even the most progressive organizational models. In an upcoming conversation on our podcast with DIMO’s CFO Rob Solomon, we reflected on the fact that DAOs and Web3 protocols effectively push us to think about developing an organization in a way that mimics how we build cities: optimized for diversity, evolution, and complexity and able to grow super-linearly as driven by the laws of social networks and not just sub-linearly like companies do, until they collapse.

Humans are learning how to create transparent protocols as ontologically convergent and composable layers. If we accept (and participate in the development) of these composable ontologies and we decide to build on top of them, our organizations can break free of the monopolies that characterized a large part of the last two decades, and this will come at the cost of accepting a certain ontology trade-off.

When – on the bottom of this – incentive mechanisms also exist for the participants of the network to actually build the underlying infrastructure (see for example what Helium is doing with Lorawan) the opportunities to build a portfolio on top of such shared ontological and infrastructural layers effectively creates tensions that the concept of building “inside” organizations can’t contain.

These mechanisms essentially bring such strong market-driven, Darwinian innovation dynamics that make our idea of “using P&L internally” as a forcing function for how we structure teams inside our organization, pale in comparison. It’s open-source economy, on steroids.

This transition will oblige organizations to reconsider where their boundaries stand and will push us to rethink the meaning of things such as “organization”, “purpose” and employment.

Stay tuned for more research on this.

Do you want to learn how to create entrepreneurial and ecosystemic organizations?

Join us at the upcoming 3EO Masterclass in September:

Before You Go!

As you may know, everything we do is released in Creative Commons for you to use. In case you’re getting value out of these reads and tools, we encourage you to share with your friends as this will help us to get more exposure, and hopefully, work more on developing these tools.

If you liked this post, you can also follow us on Twitter, we normally curate this kind of content.

Thanks for your support!

Simone Cicero