Defining the Ecosystem Domain: Ecosystems, Arenas and Jobs-to-be-done

How to map an Ecosystem? Let’s explore how to create a manageable breakdown

Simone Cicero

Abstract

With this installment, we inaugurate a series called Platform-Ecosystem Atlas a series aimed at giving our readers a strong frame of reference of everything related to platform-ecosystem thinking that will likely lead to a more structured publication such as a book or new whitepaper. Subscribe to our newsletter if you don’t want to miss a thing!

In this post we’ll share with our adopters a structured approach to defining and understanding the ecosystem for which one may want to design a platform strategy. We also present the Arena Scan, a new – and not yet official – tool that we increasingly use to make a first breakdown of the ecosytem. In this post we also share our views on the need to move away from strictly customer-problem centric ways to frame an opportunity in favour of framing more “systemic outcomes” that the entities involved in particular sub-domains of the ecosystem are looking for.

When approaching ecosystem-thinking, teams often – and wrongly – start from an inside-out perspective. It’s not rare that a team approaching platform-ecosystem thinking will start from one of the following tenets: “we have a new technology and we want to build it as a platform” or “we want to build a data platform: if we intermediate and facilitate transactions we will be able to generate, and monetize data”.

In our experience at Boundaryless, dating back almost ten years now as the first versions of the Platform Design Toolkit was released in 2013, the most promising approach has always been, instead, that of focusing the first steps of the team into clearly understanding the existing ecosystem dynamics.

It’s really important to understand that key differences exist between building traditional products and building multi-sided, complex platform-ecosystem strategies. In the former situation the focus is around one customer and the problems this customer faces and the objective is to create a better solutions to such problems. In the latter we are supposed to look at the context from a systemic point of view and create a strategy that actualizes the entire set of players that interact around common goals and, most of all, to understand the idea of systemic outcomes.

Indeed, as technology and other enablers grew massively the potential at the edge (that of the small actors), the focus of the designer needs to switch from solving one isolated consumer problems towards finding better strategies that allow the production and exchange of more systemic value that works for everybody.

For designers, the key becomes answering questions such as:

- who are the actors involved in the ecosystem and what roles do they tend to play most often in the interactions that make up the ecosystem as of now?

- around what systemic outcomes (outcomes that depend on many players interacting) does the ecosystem evolve and coalesce, and with what phases, aspects, layers and steps can we describe it?

- what are the drivers that each of the players has, and what are the performance pressures that they face in participating?

All this has become, in our experience, a much better approach to understanding markets where the small players are gaining more capabilities by the day.

But how does one “characterize” an ecosystem beyond describing it as a disjointed set of players with “problems” and others with “solutions”?

In the last couple of years, we started to evolve our ecosystem mapping techniques by introducing a couple more concepts that are worth explaining here. The first concept we introduced is that of the “Arena”.

The concept of an arena has been inspired by the work of Rita McGrath. As we explain in our “Platform Opportunity Exploration Guide“. The original framing that McGrath gives about arenas sounds like a space of opportunity “characterized by particular connections between customers and solutions, not by the conventional descriptions of offerings that are near substitutes for one another”.

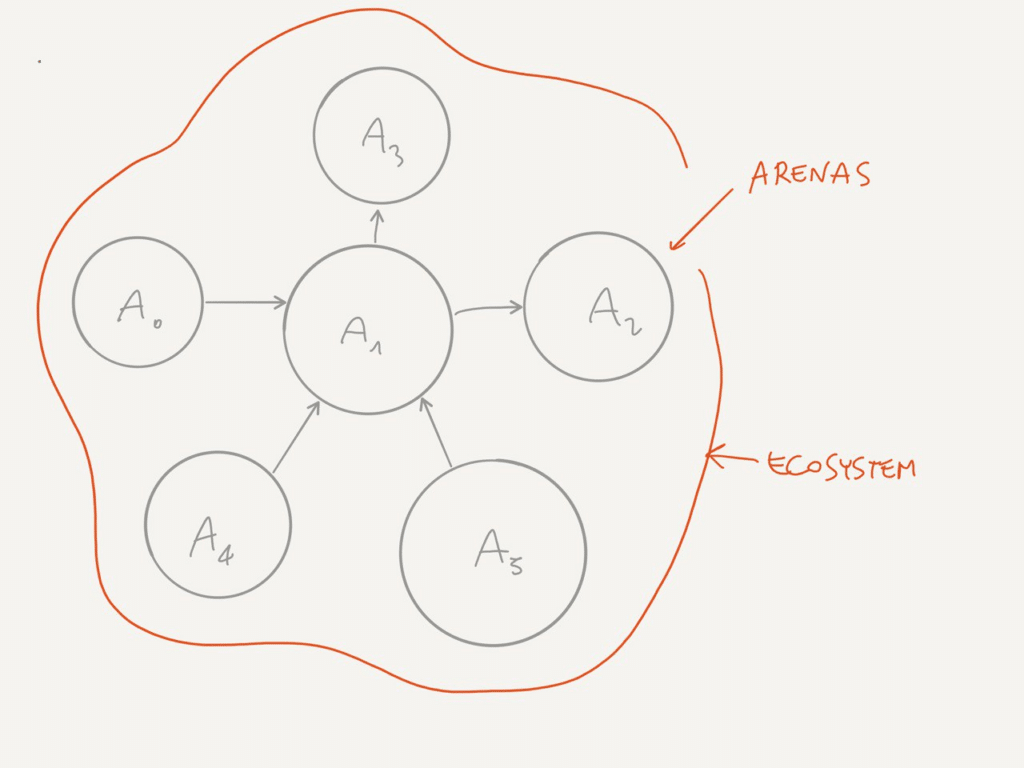

McGrath points out the connection piece as essential: if we couple McGrath’s further consideration that – as digitalization of transactions increases – we’ll see more “market based” transactions and less “firm based transactions” we can understand arenasas particular “sub-areas” of an ecosystem – where the latter is to be seen as an even broader and more complex set of players interacting across different systemic outcomes, and different contexts.

If we’re trying to map out an ecosystem therefore, we may want to think of it as a very large context, where numerous (several tens of) types of entities interact, playing certain roles in replicable, common, areas of interactions. In this context, arenas shall be seen as “zones” or “sub-areas” that all together mix up and connect composing the ecosystem.

A bit of Glossary

Entity: any player in the ecosystem

Role: the type of roles that entities in the ecosystem tend to play consistently

The various interactions between entities that make up arenas can be described in many different ways: one possible way to look into those interactions is by using the lens of Jobs To Be Done.

According to jobs-to-be-done father Anthony Ulwick, a (core functional), Job-to-be-done can be described as a statement essentially composed by:

a verb plus an object of the verb (noun) and a contextual clarifier

(example: buying a meal during a drive to work)

Always according to Ulwick, jobs-to-be-done are:

- stable (don’t change over time);

- have no geographical boundaries;

- are solution-agnostic;

Lacking a better framework we believe there’s value in Ulwick’s way to frame how users express needs in search of outcomes but we suggest a that a less rigid and less user focused approach is needed if we are to deal with the complexity of ecosystems.

We find the idea of single user-focused jobs-to-be-done not optimal for the challenge of understanding the collective and collaborative nature of ecosystems: the traditional focus around one single user has been instrumental to some of the shortcomings of user-centered design thinking that characterized the late 20th century, and the start of the 21st century.

We advise framing the customer needs systemically and relationally (looking into interactions more than problems), and avoid a systematic downplaying of the producer side activities. The idea of a brand producing a solution to get a job done in a better way for a consumer to which the solution has to be administered is no more fit for purpose.

In our approach and technique of ecosystem domain mapping, we often speak of arenas, instead, as being characterized by “clusters of jobs to be done“, where these clusters involve different entities in interaction. Such clustered interactions around somehow relational jobs-to-be-done is to be seen as producing certain continuous systemic outcomes. Such outcomes are often functional to or connected with other anticipating or following “phases”. Such clusters of interactions happening in the ecosystem are often either:

- enablement of another set of entities achieving other systemic outcomes at a higher-order system;

- or a phase of a chain of connected arenas (in a sense, “before” or “after”).

Such a comparison element (before/after, enabled by/enabling of) helps when teams are tasked to map a large ecosystem. Even if we believe that a certain “objective” map of an ecosystem can be done, we always have to factor in that the perspective of the mapper clearly defines the initial “focus” and that the team will then move from there, exploring what arenas exist before or after, or above (enabled by) or below (enabling). It’s indeed important to embed a focus in a domain map cause the focus tells us something about the mapping team: the arena in focus will likely be one where the team has been spending time on, or maybe has domain expertise about, or even some assets to be leveraged.

A good example could be the agricultural ecosystem; let’s imagine we have to map such an ecosystem, with the aim of developing a platform (enabling and network based) strategy; should we start from an arbitrary small and inadequate filter of the jobs-to-be-done such as with:

- harvesting all apples on an orchard during the harvesting season;

Or look instead into:

- the several phases involved in the complex ecosystem such as selecting seeds, planting, harvesting, storing and trading, transforming, distributing, consuming…

- enabling layers such as: researching for the best seeds and treatments, executing logistics to support transportation, …

- enabled layers such as: developing and sharing recipes, etc…

- the several entities involved in the process and the “clusters of jobs-to-be-done” that they are involved in across the phases and layers;

One can easily see that it would be extremely hard to catalogue all specific jobs-to-be-done at this very open stage required in preparation of pondering the challenge of mobilizing all participants.

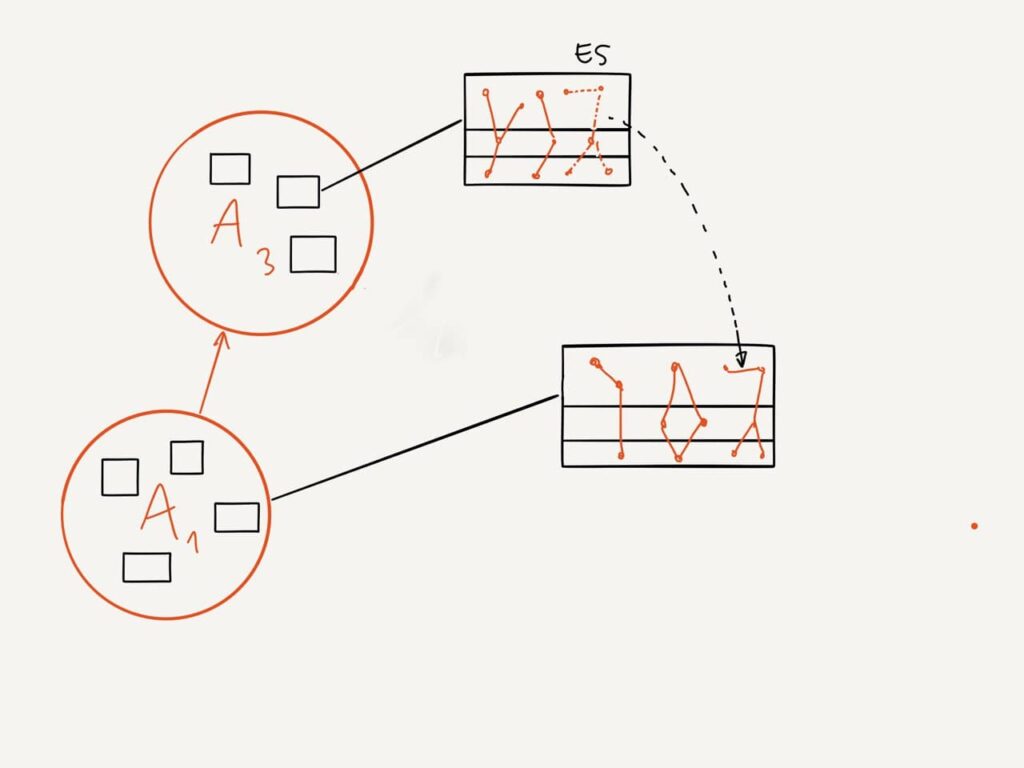

Let’s look into a visual representation of an ecosystem as a breakdown:

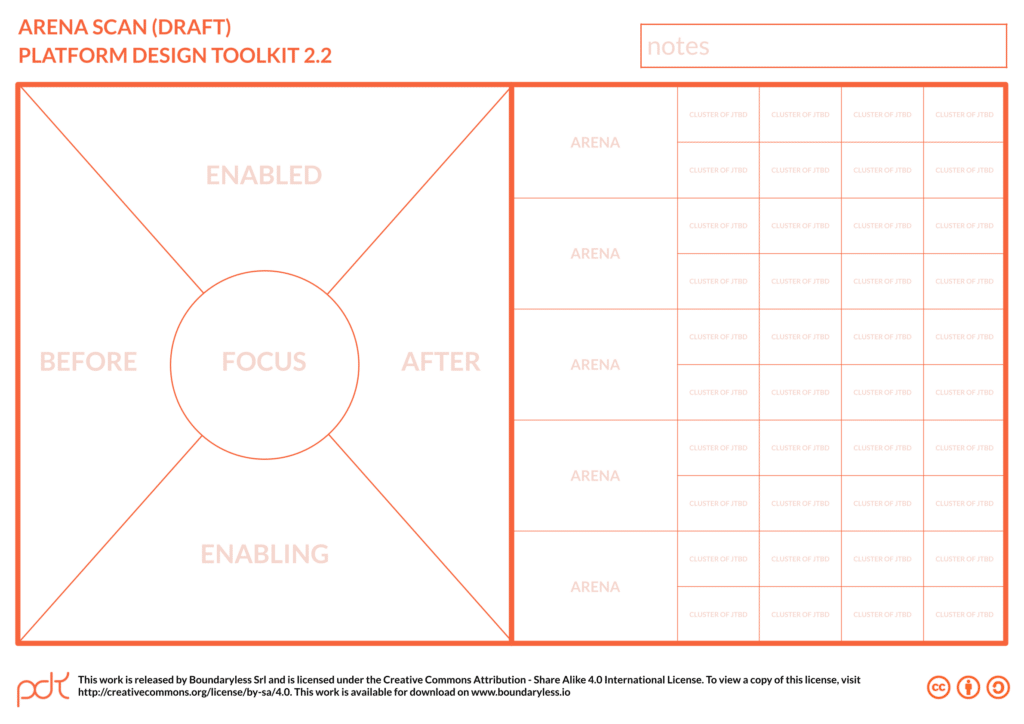

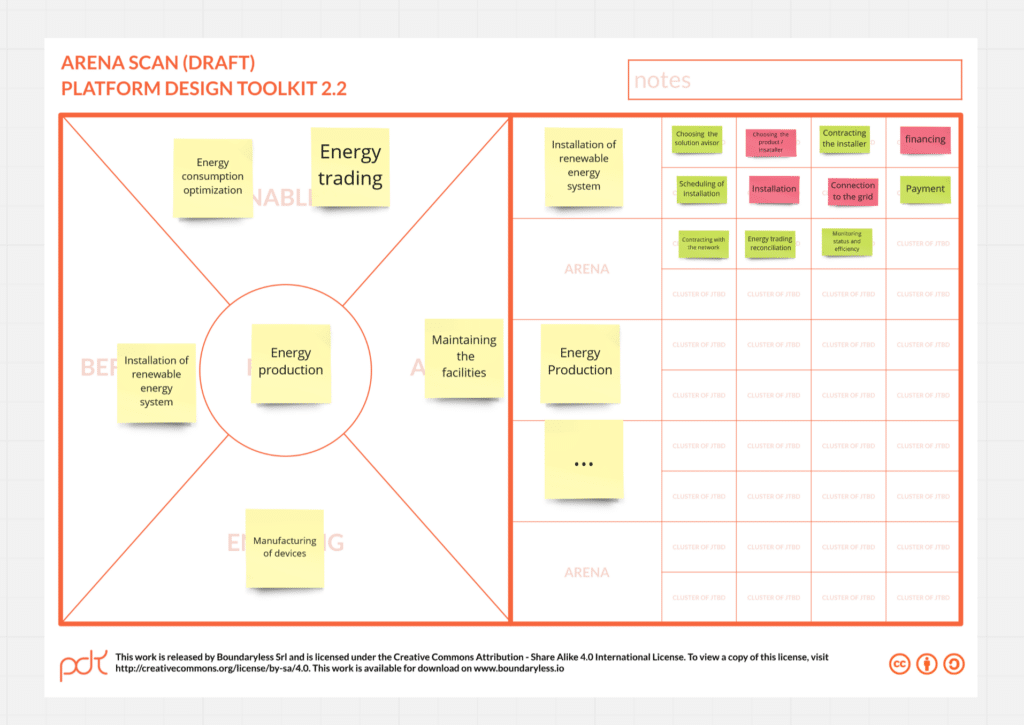

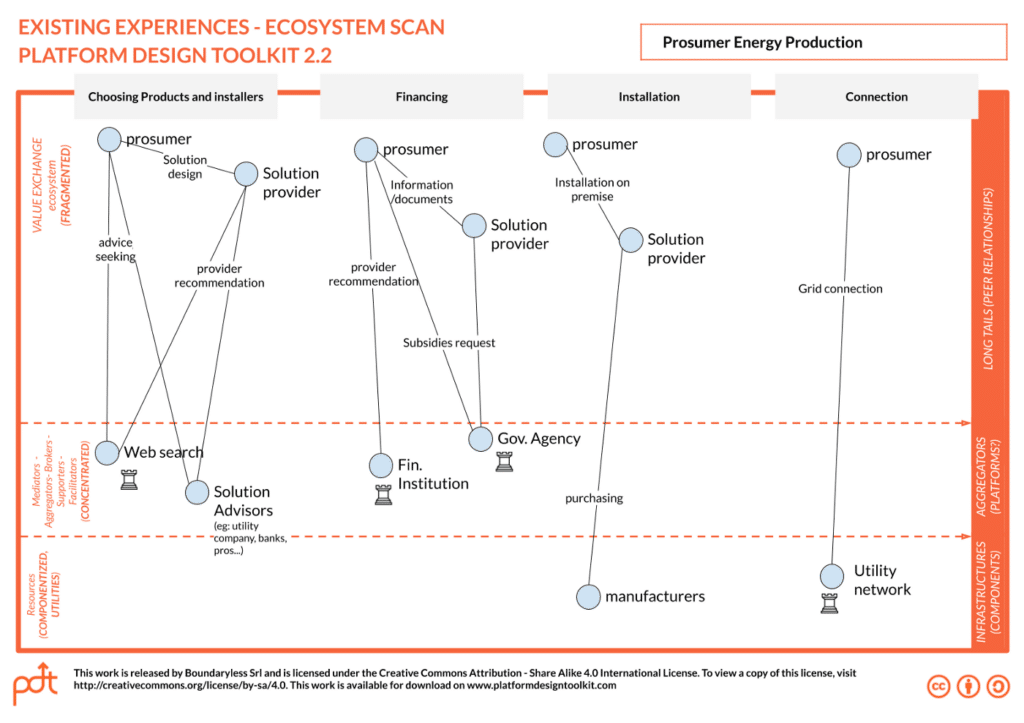

We normally collect such an ecosystem representation by first doing a breakdown of arenas and – as a following step – we proceed at breaking down arenas in smaller pieces the clusters of jobs-to-be-done. Once we identified arenas an their systemic relationship an after we listed – for each of the arenas – the composing clusters of jobs-to-be-done, we move into scanning those clusters through the three key layers of digital markets: niche, aggregators and infrastructures according to our Ecosystem scans.

To make an arena breakdown one doesn’t really need a “template”: despite that we created one called the Arena Scan: we just released the additional canvas in beta to our community of certified trainers (check it out and download it here if you wish to use it). Instead for the extensive mapping of the single clusters of jobs-to-be-done across the three layers one can use our Ecosystem Scan. The three-layered scanning technique is well covered in our Platform Opportunity Exploration Guide but its very intuitive: we have to map niche players on the top, mediators, brokers, hubs in the middle, and consumed resources, assets, components and infrastructure on the bottom.

The three pictures below represent the Arena Scan template (download it from here), an example of a partially compiled arena scan, making a reference to our public example regarding the solar energy installation market (available here), and an example of an ecosystem scan from the same.

This initial mapping of the ecosystem as a breakdown of:

- arenas (composing wider ecosystem in systemic relationships);

- clusters of jobs-to-be-done (representing sub-phases of each arena);

provides – in our experience – a rather formidable understanding of what’s going on in the space the team is targeting for platform transformation. Without such an understanding a platform team can’t really articulate a significant strategy: in a way similarly to a designer trying to fix a problem before even understanding it.

After the first scanning has been completed it’s important to pay attention to the information that is emerging from scans: sometimes, arenas lend themselves to be reorganized in a way that is slightly different from the way we organized them before actual performing of the the scanning, only based on assumptions rooted in our domain expertise.

We suggest designers to re-cluster and reorganize the clusters of jobs-to-be-done as better logical continuity emerges: some good way to seek this reorganization could be about:

- re-cluster arenas according to recurring entities/roles involved;

- logical contiguity emerged after the mapping;

- domain expert feedback;

etc…

A logical reorganization of arenas will lend itself to a much easier application of value chain analysis through Wardley Maps and the application of the Essential Platform Plays (as well described in our Platform Opportunity Exploration Guide) with the aim of identifying how the existing landscape can be transformed through the logic of platform and ecosystems.

Conclusions

Understanding the ecosystem you’re designing for is an essential enabling step of any platform strategy. We advise to use a systemic mapping approach such as the one described here, with a first order mapping of arenas and a further breakdown of arenas into interactive clusters of jobs-to-be-done (sub-arenas).

As we will see in following installments designing a platform-ecosystem strategy is characterized by a number of synergistic elements of value proposition:

- some more focused on providing a certain specific user with an enabling solution (such as a product or service bundle, or SaaS);

- others about enabling interaction between two parties (such as with services marketplaces, developer platforms for apps and plug-ins) and thus more focused on building optimized channels for peer-to-peer transactions.

In both cases, more canonical implementation of jobs-to-be-done analysis (especially in the former case), or service design thinking (especially in the latter, with the aim for example of reducing frictions), will provide fundamental value and should be pursued, but once a more ecosystemic description of the context is achieved through the Arena and Ecosystem scanning techniques.

Are you curious about developing mastery on the application of such techniques, access our beta tool releases and more?

Join us at the upcoming Platform Design Bootcamp in June:

Additional resources:

To learn more about our ecosystem scanning and value chain analysis techniques check:

Before You Go!

As you may know, everything we do is released in Creative Commons for you to use. In case you’re getting value out of these reads and tools, we encourage you to share with your friends as this will help us to get more exposure, and hopefully, work more on developing these tools.

If you liked this post, you can also follow us on Twitter, we normally curate this kind of content.

Thanks for your support!