The 3 Key Challenges in making your Organization Platform-ready

Combining the unbundling of capabilities, innovation portfolio management, and entrepreneurial organization models.

Boundaryless Team

As a matter of fact, contemporary organizations — most likely evolved in the industrial age and now facing the shift to the platform age — are now confronted with plenty of challenges. One of the most important of those challenges is certainly the need to reduce organizational and technological debt and the overall elimination of the distance between the inside and the outside of the organization itself, as keeping these imaginary boundaries — in the face of plummeting transactions cost and technological pervasivity — make now little, and even less, sense.

The key answer to this challenge, we posit, sits essentially in three essential steps that, most often, represent a state transition for incumbents that have postponed their organizational and technological evolution for too long:

- unbundling the organizational capabilities;

- instill platform thinking literacy;

- let the organization re-bundle around a new set of priorities, and market signals through entrepreneurship.

How’s this process supposed to work then? In this article, I’ll expose how this process goes — based on our work at Boundaryless with pioneers — and why it’s crucial.

In our existing body of research, our unified market theory, we explain why the digitally enabled market presents three key “business types” opportunities — that go beyond the more consolidated classifications of the industrial age — as options for organizations to play a role in the market:

- Long Tails, Niche players that interact around customized products and services;

- Aggregators that connect producers to consumers and power continuous learning;

- Infrastructures that provide modular enablers.

Long tails, niche players are the big winners of the 21st Century. Technological pervasivity gives the independent players an extremely more competitive set of powers. Easily leverageable technological capabilities that are available ubiquitously and at commodity price, make small niche players powerful, nimble, and economically sustainable in an increasing set of business context. Not only single players can now compete with corporations, but they can also easily team up as transaction cost decline and cooperation among individuals becomes easier to create small but powerful team units.

Aggregators provide these small powerful players with even more potential, as their role in the digital economy is to connect producers to their audiences. They become — in John Hagel’s words — trusted advisors and talent agents. According to Ben Thompson aggregators have a direct relationship with users and (almost) zero marginal costs for serving users: these characteristics effectively change the game of the industrial age, where advantage was normally rooted in controlling suppliers and solidifying supply chains, into a game of platform economics where the advantage is — increasingly — in controlling demand and connect it with suppliers.

Despite the new rules of the internet give aggregators these advantages, as the power balance continues to shift towards the small, aggregators are also challenged. As markets fragment into vertical and nicher spaces creators and talented producers can create more direct connections with their audiences through social media. On the other hand, technological advancements in crypto tech question the centralizing nature of aggregation with promises of further decentralization.

Nevertheless, the power of providing a solid and compelling UX in connecting a customer with the providers the user is seeking for, providing standardized transactions, a set of supporting services to streamline producers’ operations, and letting participants consolidate their social capital into digital identities and reputation systems (check our six platform plays), provides such as a set of benefits that make us think aggregators are here to stay.

Infrastructures provide aggregators, and sometimes niche players directly, with modularized and composable capabilities, in software, computing, logistics, manufacturing, marketing, distribution, customer engagement: the plethora of API-powered services, as-a-service infrastructures, is so abundant, cheap, and available that some of the providers of such services fade in the background of everything that happens on the internet.

As we move forward though, the overlap between aggregators and infrastructures becomes fuzzier: all boils down to a mix of aggregation (the connection between demand and supply) and enablement (provision of support services and modular technology) that follows a slightly different layering.

At the end of the day digital platforms increasingly provide a combination of:

- a marketplace functionality, that aims at delivering a step-function improvement with regards to the existing experiences available in the market, enabling consumers of certain services or products to connect with the right producers;

- a solid product/services offering, normally targeted to the producers on the marketplace, focused on providing a core set of enabling features that are potentially complemented by an ecosystem of third parties.

- These third parties normally develop additional complements in the form of “extensions” (thus the idea of an “extension platforms”) of the core set of features, something we can call the “main UX” that the platform provides to its users.

By looking back at the layering, we can see how more precisely these elements stack up:

The Example of Shopify

As the stack may be hard to comprehend as an abstraction we can look at an example. Shopify is probably one of the most advanced companies in the world at the moment and is able to play out in most of these layers. Shopify uses modularized technological enablers such as Stripe’s APIs, and Google Cloud to run its systems and provides:

- a core set of features (a main UX) to e-commerce players to build a shop online;

- a marketplace that connects sellers to consultants (experts);

- a first level of extension platform through “apps” you can plug into your shop;

- a second level of extension platform through “templates” you can adopt for your e-commerce website.

Indeed Stripe is also internally organized to deliver four macro value propositions they call (more details from this conversation with Alex Danco):

- Core: the operating system nucleus, the core of the e-commerce platform;

- Merchant services: to help merchants with improving their presence and capabilities (for example with the expert marketplace);

- Ecosystem: the whole workaround extensions and developers engagement;

- Shop: their social shopping app that helps customers create more engaged relationships with the shops they love.

As one can see, Shopify’s main target is an online shop owner and the company weaves around this main customer an ecosystem of experts that are connected to the customer through the experts’ marketplace, and of developers that can provide the shop owner with both “apps” ti integrate further functionalities and “templates” to style up and personalize the storefront. Apps and templates effectively both “extend” Shopify’s user experience although apps are more properly extensions in extension platforms’ terms — as they actually “extend” the main UX offered by the core product, while templates are more about what the actual buyers see. It also must be considered that Shopify doesn’t aggregate the end-user side of the market demand if not marginally with the brand empowerment features provided with the Shop app.

Seen through these terms Shopify’s platform strategy is slightly unusual: they effectively have a SaaS offering targeted to “consumers” (the demand side) of their service marketplace (Shopify Experts) and they don’t really aggregate demand from the actual market’s end-user (the buyers). This is comprehensible if we think that the user of Shopify main UX is an actual “producer” in market terms (a professional or company selling merchandise) and that Shopify chose to enable what they call “high trust” commerce, thus entrusting their customers to be able to generate multi-channel demand that doesn’t need the kind of aggregation strategy that Amazon marketplace or Airbnb have (aggregating consumer demand and providing discovery tools).

The need to map the outside trends with the organizing models

As I’ve been able to introduce and describe already in my recent post on the common protocol of organizing, companies that are leading the way in terms of market impacts show great resonance with such market trends. They succeeded to intentionally shorten the distance between their inside and the outside by adopting organizational artifacts that resonate with market dynamics and indeed can be easily mapped on the just presented layers.

The key trend we see emerging is certainly that of reinventing organizations around self-managed, entrepreneurial units that seek continuous market validation (or a directly related KPI) and product ownership. We know how micro-enterprises in Haier’s, or Zappos’ circles continuously seek positive profit and loss by exposing their set of services.

Similarly, the idea of stream-aligned teams in direct touch with customer signal is crucial in the Team Topologies taxonomy: a software-centric approach to team structuring that is gaining ground as a widely adopted organizational development framework in the DevOps space. At Amazon teams also optimize themselves for KPIs that express a direct and artful connection with generating customer value even if positive profit & loss is not enforced at a granular level.

The services that such customer-facing units provide to the market may vary widely: some of them run platform-marketplace strategies, others create niche services — that in turn can be provided inside existing aggregators — others provide basic enabling services or APIs that can be framed at the “infrastructure” level. Some of the most enabling units — with less of a customer-facing nature and more of a “business powering” one — such as so-called shared services platforms in Haier’s Rendanheyi or the shared funded services in Zappos market-based organizational model, or platform teams in the Team Topologies framework essentially provide more “infrastructural” services with the aim of enabling customer-focused units focus on their specialties. The more a certain service needs scale, and the less it constitutes a specific “competitive advantage”, an IP that is worth controlling, the more organizations are lured to externalize interfaces to them. Opening up and weaving ecosystems around formerly internal “platforms” is done, on one hand, to maximize the consumption of the provided services and — most importantly — with the aim of not falling short of innovations. As we move past the industrial age it’s becoming ever more clear that rarely innovations happen inside a certain organization: innovations are identified as the result of emergent patterns of interaction that need to be spot, measured, enhanced, and enabled by a platform (as in Simon Wardley’s view of ecosystems as future sensing engines) through its interfaces.

This thin, disappearing line between the inside and outside of the organization can also be appreciated in this talk by Ellen Li and Konstantin Tennhard — from Shopify’s engineering’s team. In “Building Extensible Platforms”: around minute 18:30 Tenhard speaks extensively about the need and potential of mobilizing internal teams in developing extensions for the core Shopify experience as well as external ones.

The promises

The promises of adopting such a way to characterize organizational capabilities, products, and go-to-market strategies are extremely luring. As we already explained, one immediate gain consists of introducing interfaces and, thus, monitorability (the capability of measuring consumption patterns, generating data) and marketability (the possibility to marketize certain service/product interfaces and thus increase efficiency). Thanks to this, by creating interfaces and modularizing capabilities, we can be more aware of how the so-called ILC cycles (where I stands for Innovate, L for Leverage, C for Componentize) work inside your organization: once components are unbundled we can strategically drive their evolution and — most importantly — understand when is the moment to move to higher-value services as a particular component becomes a low margin commodity. The powerfully informative data we tracked at the numerous interfaces with the market will act as guidance for what directions to take.

Furthermore, capabilities unbundling provides a stronger foundation for growth: as everything that we bring on the market today is effectively to be seen as part of a network, piloting growth from one product to another becomes easier. Spillover growth becomes an opportunity: as explained in our recent post on growth engines we may one day launch a certain product targeted to a set of customers and, subsequently, launch a second one that insists on a partially overlapping user base — an occasion that is increasingly more frequent as more products involve a marketplace aspect.

Entrepreneurial Re-bundling

It’s easy to understand how re-bundling is as important as unbundling: so what do we do in our organizations to ensure we have a full-stack re-bundling capability? Platform thinking literacy, such as what Boundaryless provides with the Platform Design Toolkit, becomes essential having employees developing the capability to see how markets can be organized through marketplaces and platforms and is an essential first step.

On top of that, such a culture and knowledge can’t be just seen as atomized and provided to the employee as a medicine: attention to praxis (the continuous application on the field) through shared frameworks, languages — needs to be also put in place to catalyze change from a place of real applications. In our experience with organizations, developing pervasive training programs, focused on the socialization of insights through communities of practice, and the integration of platform thinking in the existing innovation processes and toolsets becomes essential. On top of the most basic elements of building these capabilities, employees need to be effectively transformed into entrepreneurs by creating clear entrepreneurial incentives, mechanisms to ensure skin in the game, and orientation to continuous learning and experimentation through the responsibilization of the employee.

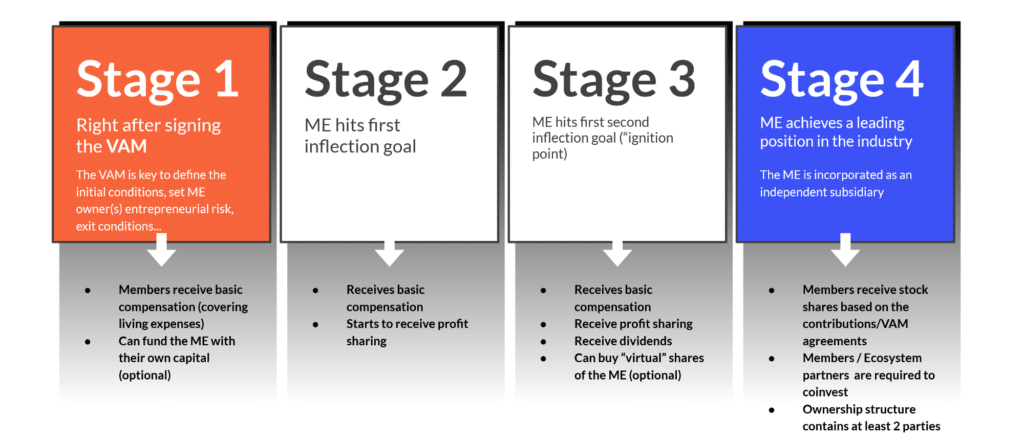

Increasingly companies provide employees with safe basic employee benefits and complement those with deliberately entrepreneurial incentives for them to create new ventures, that normally go through three stages:

- added bonuses based on the new venture progress;

- access to profits generated by the employee-driven venture;

- access to equity as a way to provide employees with the most truly entrepreneurial of all incentives — ownership.

Even giants operating in extremely conservative markets — such as Unilever — are taking steps in such a direction by creating new salary programs that allow much more personalization beyond a basic salary.

A pic recapping on how Haier does it under Rendanheyi is also provided below:

Strategic coherence through a portfolio lens

The role of strategic leadership in such an unbundled and entrepreneurial organization boils down to holding the big picture together. Organizations need to develop a shared vision of their portfolio also because, increasingly, taking strategic decisions about one particular piece of the puzzle may depend on considerations deeply rooted in an understanding of the underlying value chains and their interdependencies. Imagine for example wanting to launch an extension platform and a marketplace strategy for a certain set of services (let’s call it strategy A) in a particular opportunity space where you also commercialize a certain hardware solution (strategy B). Imagine now that strategy A — to achieve maximum reach — is premised on commoditizing the hardware that is so crucial for strategy B: there’ll be certainly frictions between the organizational entities that bring to the market the different value propositions.

To solve such frictions you’ll need either:

- a fully unbundled interface (including the profit and loss responsibility of each unit) between the two strategies, positing that strategy A could be executed by leveraging on third party hardware competing with that central to strategy B: in this case, you’ll essentially let the market do the job as the market penetrates very deeply inside the organization and effectively prevent any organizational debt and over bureaucratization to happen;

- a solid capability to take decisions and enforce them cascading through the organization for example by looking at re-grouping certain capabilities in divisions or substructures that manage the interaction between unites more systemically — something similar to what Amazon does with the OP1-OP2 process.

Strategic coherence is effectively a major challenge for modern organizations: incumbents will need to switch from rigid command and control structures towards more dynamic processes for achieving coherence of strategy but this will solve the problem only to a certain extent. At the same time, the capability of the market to self-achieve coherence through dynamic collaborations between composable elements, low transaction costs contracting, and technology platforms represent a tough challenge for a bounded organization and push continuously towards adopting more porous and unbundled structures at all the layers so that the continuity between the org and the market is more marked.

As transactions cost plummets this unbundling process is unstoppable and relentless: if you feel that your organization is now more into finding out special constraints that — somehow — seek to explain how this is not applicable to your context you should be asking instead “how are we going to adapt to it?”