Why Building a Visual Product Portfolio and creating shared innovation practices is essential for Adaptive Organizations

In this piece, we explain why creating shared visualizations of product portfolios is key to developing success in organizations and what are the pillars needed to achieve a coherent portfolio-level strategy for the market.

Simone Cicero

Emanuele Quintarelli

Luca Ruggeri

Abstract

Our most ambitious and successful clients are the ones that not only do focus on bringing a single innovation initiative to the market with a structured, validation-oriented, platform design approach but the ones that recognize the need to look at their organization, capabilities, and strategies from a portfolio and systems perspective.

In this piece, we’ll explain why this is important and what pillars your organization needs to pursue to be able to achieve a coherent portfolio-level strategy for the market.

Subscribe to our newsletter if you don’t want to miss a thing!!

Why is this important?

At Boundaryless we’ve been iterating towards this approach almost intuitively during the last couple of years: as we approached more ambitious customers, some of them with large organizational settings and vast capabilities, the ability to enact full product portfolios became more central. More recently, by the way, we started to identify a lot of resonance between our approach and existing implications of socio-technical systems.

A few days ago, as I was browsing LinkedIn, I encountered an interesting comment from Team Topologies’ Manuel Pais. In a comment (slightly edited) to a reflection from experienced software architect Kevin Stewart, Pais stated that when thinking about increasing the capability of an organization to coherently and efficiently build products:

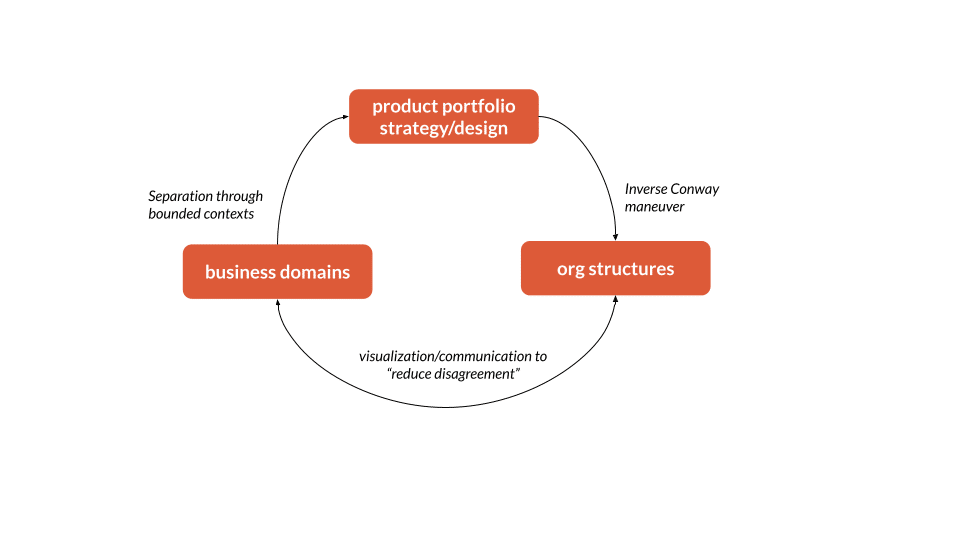

“You need to think of the triad that (tends to) mirror each other: org structures, system design, and business domains (such as with the concept of bounded contexts in Domain Driven Design).

I found it extremely clear how both – Pais and Stewart – pointed out that our interpretation of Conway’s law is often too focused on organizational structures and less focused on the communication patterns that such structures afford.

Indeed, despite our common interpretation of Conway’s law that “you ship your org chart” the original key statement was that:

“Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.”

with a rather specific reference to the way, teams communicate rather than how we structure our team’s shape or hierarchies.

Pais continues:

“Conway’s Law talks about communication lines as well, so there’s an ongoing, day-to-day influence on the emerging technical systems related to how well and often teams interact to clarify their needs and boundaries.

With poor interactions, you tend to see systems getting messier, with an unclear split of responsibilities, duplication of data, ad-hoc solutions that don’t scale, etc….”

But what should this ongoing communication be about?”

If the aim of the organization is to create a modular offering that can be easily extended by inside and outside players (and we’ve seen in another post how critical this is in modern product thinking), a modular organization and a modular product taxonomy are needed.

This is an important factor: the systems an architect creates mirror not only the communication patterns but also the domains of thought in an organization. These domains of thought, also known as bounded contexts, are the spaces where participants in a process share a common understanding of the domain they’re operating in, such as a product domain.

In another conversation we had with Alberto Brandolini, that is coming up on the podcast on the 21st of March, the legend of Domain Driven Design (a practice that was born exactly to integrate the impacts of shared domains of thought, and the role of language in how we develop software) said something very important on the implications of reaching coherence in an organization through agreements.

According to Brandolini, reaching agreements is often an understatement: instead, what we should seek is rather a visualization of our different perceptions of the domain we share, even clarifying disagreements. Let me share with you a – slightly edited for clarity – quote from an upcoming episode of the Boundaryless Conversations Podcast:

Reaching an agreement is one of the most expensive and sophisticated activities of human beings in the organization – underrated and underestimated: “Oh, we just need to reach an agreement”…That might take ages.

A lot of it is about visualizing instead of talking: that speeds things up.

“…we shouldn’t necessarily try to reach an agreement. We should try to visualise disagreement instead, so that we can get a snapshot of our current level of understanding, including the current disagreements: I would split reaching an agreement from visualisation.”

The following quote is even more important to ponder:

“The only thing we agree with is: is this the way we all see this today? Yes: fine. No: is it honest? Yes. That’s the best we can do.”

Then if we need to converge, every convergence, every agreement has a cost. And the cost might actually skyrocket in a larger distributed organization.

According to Brandolini “every agreement has a cost” and this cost skyrockets in large, distributed organizations. But, regardless of how difficult this is, coherence is something we definitely want to achieve in an adaptive, performant, modern organization as it is the only affordable alternative to control, the dream we chased for the whole industrial age (check out the conversation we had with Rita McGrath about coherence vs control).

So how do we make it possible for the organization to remain coherent from a product and offering perspective? The answer to this may sit in this quote from Jabe Bloom, from a previous conversation on our podcast:

“… there’s a significant push inside of organizational theory right now to say, we need to decentralize decision making. […]

…organizations […] decentralize the authority without decentralizing the information, or the ability to make those choices. So, they don’t think through things like how do we make better decisions in a decentralized way? What information needs to be available to make these decentralized decisions?”

I think creating a set of organizational methods and ways of working around those things becomes really important. I’m a big believer in praxis: you need to create the conditions under which an organization can practice working in those ways.

FromPlatforming Inside and Between Organizations: differentiation, scale, and scope— with Jabe Bloom

Operationalizing this approach

The typical approach we’d follow with a pioneering organization that understands the importance of achieving coherence through visualization, common practice, and organizational enablers are composed of four essential threads:

- A Portfolio-level mapping of areas of opportunity first and services, and products then

- The adoption of a shared language, and common literacy

- The creation of organizational enablers that allow the teams in the organization to autonomously (even if sustained) and quickly rearrange around opportunities to get to the market quickly

- The creation of shared playbooks and a community of practice

1. A Portfolio-level mapping of areas of opportunity first, services and products then

This mapping work normally unfolds along three key lines:

- mapping arenas and information about the target customer ecosystem;

- clearly describing recurring entities/personas/user types in an outside-in way;

- mapping products according to a shared and ever-iterating taxonomy.

The first thing you’ll have to do is to map the information that the organization holds about its reference market (ecosystem), and areas of opportunity. We typically do so as we explained in this earlier post, by using the concept of “arenas” as a way to break ecosystems down into smaller pieces.

For each of the arenas – that we also characterize in terms of relationships with the others – we try to collect as much information as possible in terms of domain knowledge that the teams have collected so far. We often use our ecosystem scans (a way to map interactions and players in a given market space according to the key role they play, interacting entities, mediators, and resources) but any documentation that exists can be fungible. A key first principle we adopt is also that no document and no formats are “mandatory”.

Another thing we do is to create reference descriptions of entities in the ecosystem: we normally use our entity portraits (which provide a way to describe an entity from a perspective of evolutive potential, niche needs, and scalable interactions) and we often complement it through descriptions of the key Jobs to be done and outcomes they seek, or with any existing interview scripts. This is essential so teams can coherently converge to a common understanding of their target user base.

The last but not least thing we do is to map the existing “products” that the organization is already building to the relative users and arenas: the objective is to always know who’s targeting a certain subpart of the ecosystem with a value proposition and the stage of evolution. What we normally do is first favor the emergence of a certain product taxonomy: the identification of a product taxonomy is essential even if we’re not big fans of “enforcing” it because the world is complex and does not always fit into pre-defined categories.

In any case, adopting product taxonomies may be essential to effectively transition to a product operating model. In an article from IT Revolution that we already quoted in a recent piece on this blog it’s said:

Shifting to a product operating model starts with defining the products, which includes both internally facing and externally facing products. Defining the products is essential to identifying clear lines of ownership and accountability, and redesigning the organizational structure to align with customer needs instead of settling for traditional organizations that align around IT functions.

This has been our experience so far: defining – even light – product taxonomies favors the recombination and composition of products and the sharing of best practices and it’s, therefore, worth doing.

For each of the products in the current portfolio, we finally create some kind of drill-down capability to be able to see – for each of those – a clear description of the product essentials. These essentials are:

- value proposition, revenue model, and extensibility path (we often do it through creating a PSM model, especially with products that have the capability to create a network-enabling proposition);

- a recap of the maturity stage, often through a “validation board” that keeps a list of the most impactful assumptions that are either still open or have been validated or invalidated plus any information about the go-to-market stage: has the product achieved certain traction, liquidity?

2. The adoption of a shared language, and common literacy

Another key element of the work we do at the organizational level is often that of installing common literacy about ecosystem mapping, value chain analysis, and product design. The idea of creating shared design toolkits inside organizations is not new and becomes even more pressing as we aim at developing portfolios where a combination of products is a good outcome. It’s also important from our experience that teams adopt as much as possible shared design, development, and validation practices for two more reasons:

- it will be easier to create some kind of elite enabling team that can provide coaching and support across the organization if everybody is familiar with similar techniques;

- the leadership that has strategic guidance and capital allocation responsibility can familiarize itself with similar information assets to monitor and support existing projects (we often use some kind of common “product boards” that recap on shared information formats to make an assessment of the maturity and potential easier).

In this process, we also found that creating an articulation of a portfolio map on a Wardley map can be conducive to better strategic, portfolio-level decisions especially when decisions involve several products.

3. The creation of organizational enablers that allow the teams in the organization to autonomously (even if sustained) and quickly rearrange around opportunities to get to the market

This is another common ingredient of a solid transition towards a portfolio approach to innovation. We discussed this already a few months ago in an earlier piece, but the assumption here is that by adopting a 3EO-based model of organizing you’ll enhance the capability of the organization to swarm and evolve around opportunities in a way that is much more powerful than if you had to directly allocate resources, set up team structures, and push everything forward from the top down.

This element of the transition is really the most challenging for most of the organizations we work with as it comes through the leadership letting go of most parts of their traditional role of dictating directions and embracing a much more challenging posture which is that of exercising so called:

- architecting leadership: designing the ways teams and units can be created, can cooperate and can manage their resources

- enabling leadership: by isolating the common services that can enable teams and providing themselves a type of contribution that is much more that of a coach, investor, and advisor.

leaving entrepreneurial leadership to the teams to exercise (check the leadership breakdown in ecosystem-enabling organizations in this earlier piece).

Thankfully we don’t start from scratch but instead, we have a solid corpus of experiences, first principles, and org archetypes we can use (check out the 3EO Framework and the adoption guide) plus a lot of good examples of organizations that successfully implemented similar model, that sustains entrepreneurship in employees, starting from Haier’s Rendanheyi, Amazon’s unit-based organizing unleashed by the original Bezos API mandate, Flagship Pioneering incubation model and many more.

The key ideal components of such an enabling org structure are:

- leaving to teams the capability to manage their resources and measure them in terms of either innovation accounting and learning (in the first steps) and later through letting them manage their own P&L;

- letting the team self-form, hire, and possibly manage – at least partially – the team’s salaries (you’ll have to identify unit “owners” for this that have the final accountability);

- letting teams negotiate equity and generally have skin in the game in their own outcomes (for example by saying that if they successfully reach a certain market result – number of users, sales) – they should have partial returns or even equity in case the units become mature enough to be separated from the original organization legally.

When we approach making this happen with existing organizations we carefully go through an analysis of the constraints (legal, cultural…) and then through pilot experiments that usually give us a rather clear understanding of what can be safely integrated.

4. The creation of shared playbooks and a community of practice

The last piece of the puzzle is essentially about putting everything together. Once you have a clear market map, a clear taxonomy, common languages, and an organizational model that favors employee initiative you’ll have to create a so-called playbook: an org-shared approach that describes the best way to approach the challenges that teams have to confront. These playbooks normally cover things such as suggested modes for:

- exploring new value propositions and engaging in validation;

- attracting clear funding that can be self-managed in each of the stages (validation, incubation, and beyond) so as to reduce the burden on the organization on one side and the alibis available for not performing on the other

- executing most of the discovery design and validation challenges with common tools.

These are exactly the “organizational methods and ways of working” that Bloom refers to in a previous passage: social practice theory has been efficiently showing us that to really move socio-technical systems through transformative steps, common tools and communities of practice are needed and it’s, therefore, your responsibility as a leader to ensure that they exist in the organization.

Conclusions

In this piece and others we previously published, we explained why the key elements of building an organization that is able to perform in a dynamic, interconnected, and ever-changing landscape are by achieving a portfolio approach to innovation, achieved through two key essential elements:

- ensuring that teams are organized in modular, and reconfigurable ways, that they’re gradually ever-more autonomous in managing their resources as they progress through validation and product creation;

- ensuring that teams communicate properly with common languages, that shared taxonomies exist and that a common visualization of the organization reference market and existing set of products exist, is accessible to everybody and thus reduces “disagreement” and wrong perceptions.

Achieving this level of organizational coherence will give you a headstart in creating strategies that are truly ecosystemic, and composable, and increase your optionality in a world where single products can often be put in bad waters due to increasing unpredictability.

Indeed this approach doesn’t just work for large organizations: is advisable also for small ones, as they become more strategic in creating a diversity of value propositions (portfolios of bets) that make them more resilient and even anti-fragile in the face of an ever-changing market landscape.

To paraphrase an existing way of saying: every morning in current markets a radical change comes up. Every organization knows it must create as many bets as possible so as to be fast in adapting to the change that comes up or it will be put out of business.

Simone Cicero

Emanuele Quintarelli