Strategy and OKRs in the Platform Organization

Why addressing strategy at the organizational level is different than doing it inside the product/service units (micro-enterprises).

Simone Cicero

Emanuela Donetti

Revised by Emanuela Donetti — OKR Coach & Partner at Kopernicana

Strategy: a weighted word and a complex process

There is always a lot of confusion about what strategy is in an organization. It’s often said strategy is deciding what to do and not to do.

The strategy approach depends on the organization’s structure. Traditional, functional, centralized organizations often have a strategic function defining 10- or 5-year visions. In our experience, these processes, especially in larger organizations, tend to be ineffective and translate into – often scarcely understood – objectives for the underlying structures.

Even less effectively, often, in divisional or matrix organizations, the strategic function outlines objectives that conflict with operational requirements like sales, profitability, product/project marginality, or cost reduction. Most of the time the strategy remains high-level, ending up in forgotten documents.

In mature organizations, the strategic process has an element of market study and envisioning new directions and possibilities and is usually accompanied by the definition of OKRs or similar elements.

OKR, short for Objectives and Key Results, is a goal-setting framework that helps organizations set clear, measurable goals. Originating at Intel in the 1970s under Andy Grove, OKRs gained prominence through adoption at Google. The framework encourages setting ambitious objectives aligned with the company’s vision, accompanied by concrete key results (that describe the actual impact) that allow monitoring progress and success. OKRs also often have a “why now” element and are usually set quarterly and are designed to be transparent throughout the organization to foster alignment and engagement, often entailing identifying who’s responsible for fulfilling them.

Would you like to express your interest in our upcoming training on strategies and structures for portfolio innovation?

Why OKRs are important and effective

OKRs provide companies with an opportunity to move from generic to-do-lists (actions), that often emanate from apical leadership, with little connection with the organizational reality, into something more grounded in objectives and impacts, that leave the organization maneuver space and autonomy in obtaining them.

Setting OKRs is an essential step to make the strategy actionable, but often the lack of clarity in responsibilities and inflexible structures make pursuing and tracking progress difficult.

In organizations that are hierarchical, it’s therefore important that OKRs are collectively envisioned, involving all parties, to ensure they are feasible and not too disjointed from the organizational reality, and that the process of “cascading” is performed well. OKR cascading is the process that helps to align all the involved parties into shared OKRs: as an example, imagine a bank sets an ambitious goal of selling 200% more loans in a year and that this objective depends on a leaner and more easy-to-use IT infrastructure. If the IT unit is not allocating the right amount of energy and bandwidth in creating these enabling services it’s likely that the sales organization will not be able to achieve their OKRs.

If we consider the concept of the platform organization, which we have recently introduced and explained as the natural evolution of the organization in the current market, the process of defining and enacting strategy and OKRs becomes clearer and more actionable, but it requires a slightly different approach.

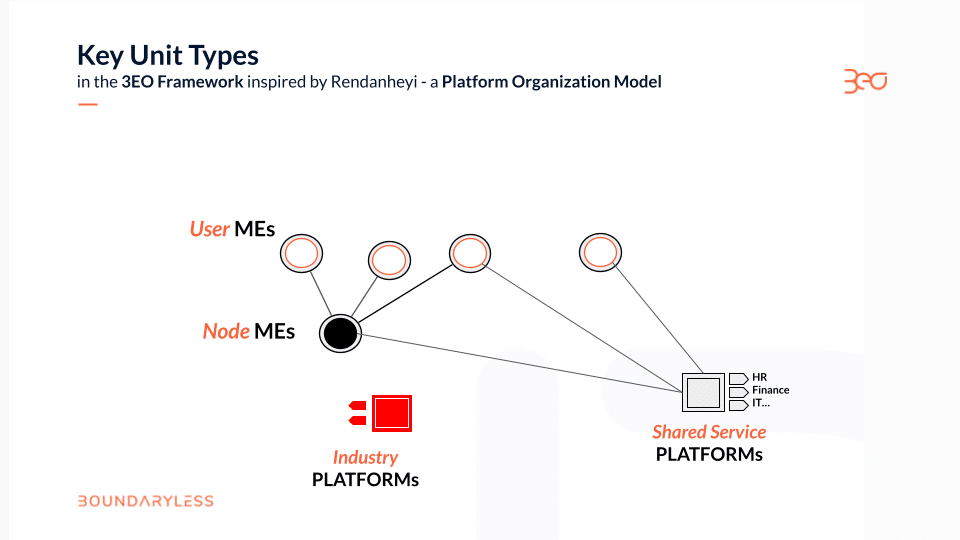

Remember, a platform organization is characterized by:

- a series of autonomous organizational units, often entrepreneurial (for this reason often called micro-enterprises), centered on the product/service they produce for the market, as part of a systemic portfolio of easily integrated services.

- a series of common, shared services supporting all product/service units – often called Shared Services Platforms;

- a series of superstructures aimed at investing, through the creation and support of new and old Micro enterprises which often group them by business sectors (often called Industry Platforms or sometimes Business Units).

Adopting a platform organizational model is suitable for the current market dynamics, needing modularity and fast access to technology’s potential and provides a clear way to implement a strategic framework.

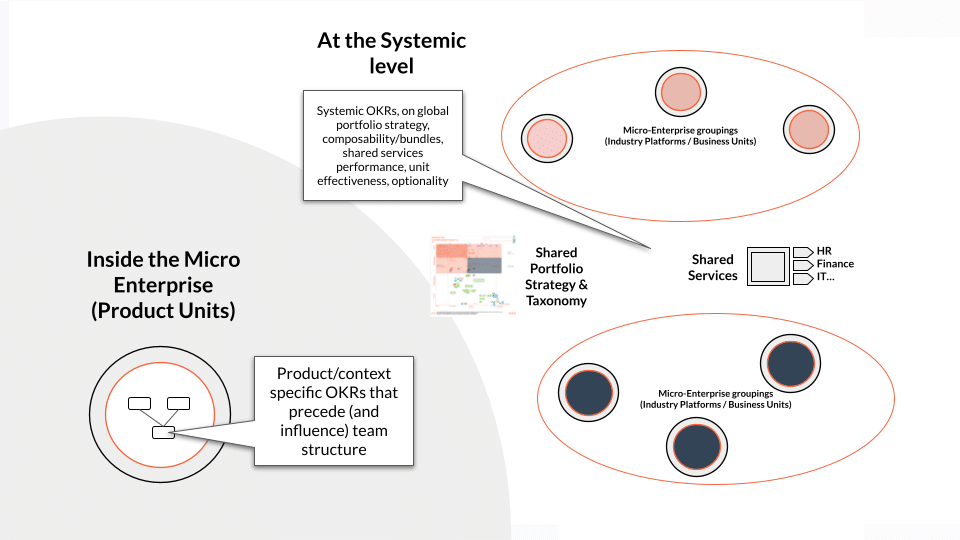

The platform organization has two essential organizational levels: a “meta” or systemic level and one internal to the product units.

On a meta-organizational level, the organization adopts a meta-structure based on micro-enterprises for clear reasons. First, it’s essential to achieve radical optionality in a fast-changing market where producing multiple options increases the chances of success.

Furthermore, the presence of many product/service-oriented units increases the number of interfaces (ways to collaborate) with the organization, facilitating connection with external partners that can connect to the company business in more elastic ways.

This approach to organizing entails a different approach to collaboration: in a platform organization one tends to avoid single points of failure and long chains of dependencies. As a general rule, every unit is responsible for its own results, collaborations are achieved through continuous negotiation and contracting, and units should always be mindful of creating alternative avenues to sourcing what they need (even from outside the organization in case the internal service providers do not perform great) and multiple ways to the market, avoiding too much of a strict dependence on org-wide go-to-market channels.

Using OKRs in the Platform Organization Context

In this context, using OKRs in a platform organization is more effective. Although OKRs should not be constrained to certain aspects, there are suggestions and elements that should be considered when setting the OKRs at the meta, systemic level.

At this level, objectives should likely cover:

- ways to achieve more optionality (e.g., with key results related to the increase in the number of micro-enterprises, product-units)

- deploying capital in more effective ways (e.g., with key results related to increasing the success/survival rate of investments)

- increase ecosystem embeddedness and integration for broader defensibility (as an example by measuring the increase in collaborations with external entities, and partnerships)

- increase in effectiveness of support structures (measuring lowering of costs, stabilization of response time, etc.).

Of course, these basic elements should only be seen as a nudge: every organization may have peculiar systemic challenges to tackle (e.g., a bad employee experience) and – first of all – should be complemented by strategic considerations rooted in portfolio and market analysis.

At Boundaryless, we believe platform organizations should maintain shared market and portfolio maps and a lively collective process involving at least the owners of the superstructures (the board, Industry Platforms/Business unit leaders). These processes would help root part of the strategy in the current product portfolio, emerging customer conversations, and evolving technologies and markets.

As an example, such analysis would make it clearer when:

- the idea of creating one or more new units to complement existing ones in promising areas is worth pursuing.

- Where should existing products work to become more composable to increase upselling and cross-selling opportunities?

and more?

Each micro-enterprise (despite the misleading term, the product units start small but can grow quite large) will then, in turn, have to develop its own strategy and its own OKRs.

In a 2020 Boundaryless interview, Kevin Nolan – CEO of GE Appliances, a well-known American organization that adopted the platform model after Haier’s acquisition – said that in his organization, the strategy was a prerogative of the Micro-enterprises (product units) and not of the group as a whole:

The Micro-Enterprise / product-unit strategy will be characterized by a much more dynamic nature and will have to adapt to market dynamics and go-to-market opportunities, largely depending on the product/service the unit is shipping.

At the micro-level (inside micro-enterprises), setting strategy and OKRs will be even more important because each product unit will face a unique market situation.

It’s crucial to understand that what happens inside the units – namely, the topology of the teams, the allocation of resources, and more – should depend on strategic objectives. Unlike the meta-level, the internal structure of product units varies heavily, depending on the product type and the strategic needs. A B2B Marketplace SaaS unit should be organized differently than a consumer product or consulting unit, and the team structure needs to adapt to the contextual strategic challenges. For instance, if the strategy analysis and OKRs define acquiring a certain customer type as crucial for product development, a new team might be created to reach those strategic objectives.

It’s important to note that different from what happens at the meta-level, which focuses on developing optionality through portfolio innovation, at the micro-level, strategy precedes team/org structure. It would be a mistake to have existing teams set their own OKRs. Instead, OKRs should precede and ignore team structure, which should be changed and adapted in line with the strategy, as Conway’s Law states that organizations ship their org charts and communication structures.

While at the meta-level, we can assume that the need to align (cascading) OKRs between units may be less of a problem (remember that the units are encouraged to develop alternative avenues to the resources they need and reduce single-point dependencies), inside of the product-unit, the micro-enterprise, it will be essential for teams to collaborate and cascade OKRs consistently. Despite at the meta-level, the general approach is that eliminating dependencies and cascading is less needed; it would still be important for the organization to perform retrospectives because there will still be synergies to find to make the organization more competitive.

Conclusions

Defining strategy in an organization is a complex, often misunderstood challenge that varies significantly depending on the organizational structure. Traditional centralized organizations struggle to translate high-level strategic objectives into actionable and effective plans, resulting in disjointed efforts that fail to align with more pragmatic operational requirements. This inefficacy is evident in divisional or matrix organizations where strategic goals often conflict with operational needs.

The introduction of OKRs (Objectives and Key Results) has provided a framework to bridge the gap between strategic vision and goals, but their successful implementation is hindered by unclear responsibilities and rigid organizational structures.

The emerging platform organizational model offers a more adaptable and effective approach to strategy execution. It delineates a dual-level strategic approach: a meta-organizational level focused on ecosystemic growth and integration and an internal level that covers dynamic and market-responsive activities within micro-enterprises (product units).

At the meta-level, OKRs should focus on increasing options strategically (by understanding market trends, portfolio shortcomings, and product composability), ensuring better unit success and support structure effectiveness. At the micro-level, they should instead be adaptable, not necessarily ignoring the team structures but ensuring that strategic objectives are set and drive adaptation of the organizational design inside the product units.

By adopting a platform organizational model and effectively leveraging OKRs, organizations can create a coherent, actionable, resilient, and adaptable strategy for the fast-paced market dynamics. This approach clarifies strategic direction and enhances the ability to achieve strategic goals through better alignment and operational efficiency.

Simone Cicero