Value Propositions in Business Ecosystems – Products, Marketplaces, Extensions

What are the key value propositions in business ecosystems? How does a product or service bundle complement a marketplace? How can we mobilize developers to create extensions to the product?

Simone Cicero

Abstract

In this installment of the Platform-Ecosystem Atlas series, we’ll give a first framework to cover the most common value propositions that can be brought to market in the context of low transaction cost, digitally enabled, networked ecosystems. Subscribe to our newsletter if you don’t want to miss a thing!

We’ll see how three main types of value propositions are typically enacted: products, marketplaces, and extension platforms and how they interoperate with each other. We’ll also look into how these three types of value propositions can be intended in different market contexts, ranging from the service industry to manufacturing and hardware.

Plummeting transactions cost

In the landmark piece As More Workers Go Solo, the Software Stack Is the New Firm a16z’s Seema Amble, D’Arcy Coolican, and Alex Rampell provided a great breakdown of a transformation thread that has been playing out widely in every industry – and especially in knowledge-related industries – for a decade or so now.

The industrial Fordist firm that dominated the 20th century based on vertically siloed processes and controlled suppliers is currently being unbundled under the pressure of a widespread reduction of the transaction cost. In a few words, due to the lower cost of transaction, services that once made sense to integrate and control top-down inside the organization are today much more easily sourceable on the market. As the cost of coordinating with partners or external providers is now much lower than it was ten or twenty years ago – teams and individuals can successfully “unbundle” from organizations and still be able to compete.

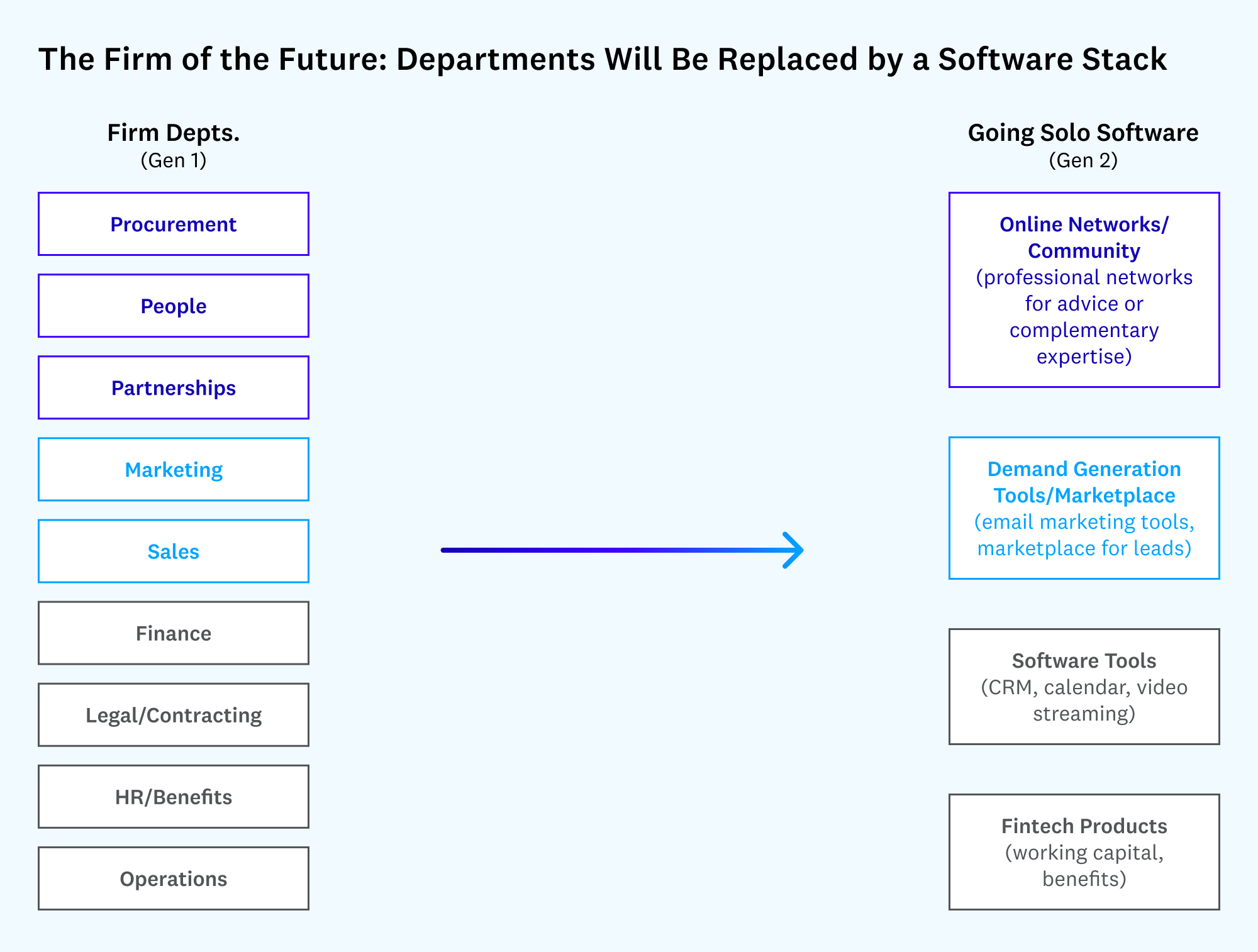

In the picture below (courtesy of a16z) we can see how the authors get to define four major “layers” of the stack along which this transition is happening:

- the need to access partners, advisors, consultants, collaborators, to procure and source suppliers, etc… are now achieved through online networks and communities (purple);

- the need to access customers, to market products and services is achieved through demand generation tools and – most importantly even – supply-demand marketplaces (light blue);

- the need to manage the key elements of the business process operations is increasingly provided by a mix of tools that the independent providers and teams can source on the market, or – increasingly – are directly provided by the aggregator itself (grey).

- the need to access capital, finance, insurance is widely accessible through fintech products, which are also being increasingly embedded (grey)

Similar trends are playing not only outside, but also inside of existing organizations. As the capability of small teams increase dramatically, the most advanced organizations, pioneering new organizational models are recognizing it, thus making teams increasingly unbundled and self-responsible of the management of their own strategies, choices, and ultimately profit and loss statements. Interfaces between teams are made more clear and “programmable”, shared enabling services are provided to teams covering finance, HR, legal, etc. Increasingly inter-organizational agreements are allowed and made easier: this allows teams to source their partners or suppliers directly on the market when internal capabilities do not provide the right solution.

Curious to know more of the organizational implications of the reduction of transactions cost? We covered this widely in our posts describing how a common protocol of organizing is emerging, as well as in a recent account of the impacts of widespread contracting on the nature of the firm.

Check them out:

We’re currently fundraising to build a software ecosystem around this space: reach out if you are interested to invest and participate.

Looking at the layers

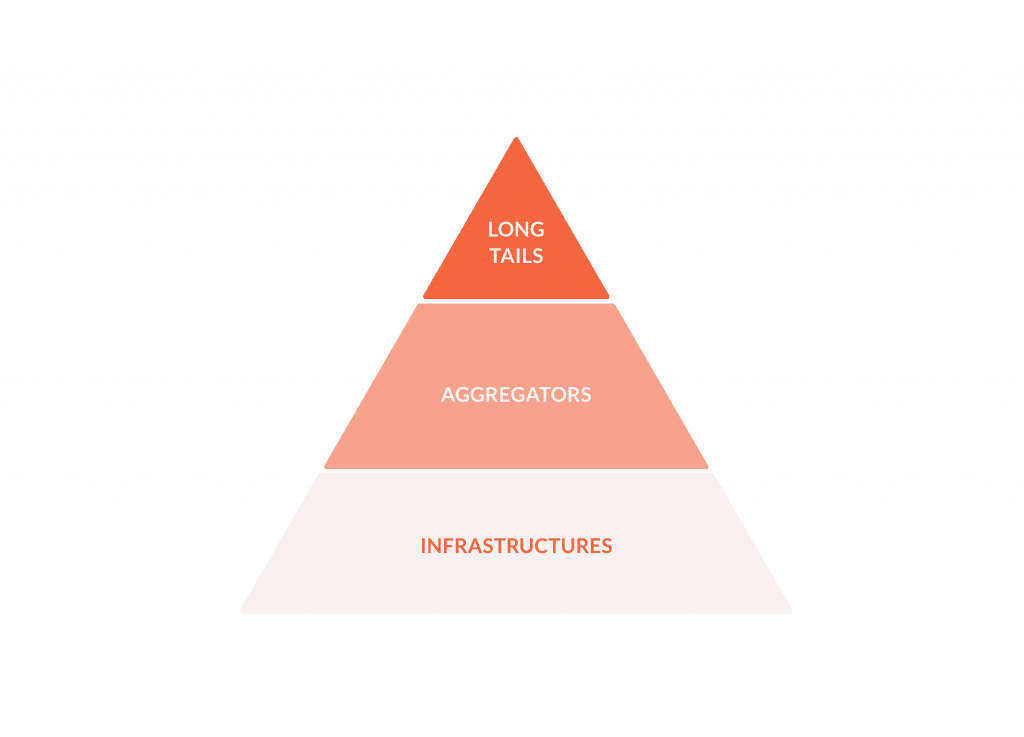

To fully grasp what’s happening we have to look at this transformation in light of the layerization that typically happens on digital markets. As loyal readers will know, “Cicero’s triangle” I presented many years ago to describe evolving digital market trends, provides a breakdown of the three key playable roles in the digital market:

- being a niche player thriving in the long tails;

- being an aggregator;

- being an infrastructure.

With niche player, we identify any content, product, or service provider that is specialized in a niche. The for niche solutions, in the context of internet-enabled markets, comes as a response to the effects of the “Long tail”. Such phenomenon – early described by Chris Anderson in 2004 – describes how, driven by technological democratization and changing customer expectations, markets now demand many solutions to coexist, as options, versus one-size-fits-all solutions that characterized the hit-based, mass markets of the 20th century.

In a few words:

- technology makes it easier to become a producer: this happens mainly thanks to cheaper means of production (think of your smartphone), open access to knowledge and software, and the widespread provisioning of computing through as a Service patterns that allow users to only pay for what they use;

- in this context being a producer needs much lower upfront investments and thus competition abounds on markets that prize diversity, plurality and customization;

- we see this happening in industries as different as music (think the millions of artists now producing their music digitally and distributing it through Spotify), craftmanship (Etsy), professional services (Fiverr, topcoder, Braintrust…), hospitality (Airbnb): the list goes on almost indefinitely.

As niche producers need to reach their customers and partners, here’s where the aggregators play a role. Such players take care of connecting supply and demand, provide filtering and matching capabilities, and enabling services (we’ll see this in detail in a moment).

Essentially aggregators play the role of:

- talent agents for product/service providers;

- advisors for buyers.

Of course, several types of aggregators exist, the main differences being in terms of how much the aggregator controls and manages the supply side: an aggregator such as Netflix essentially subsidizes, acquires, and sometimes directly produces its inventory, while one as Airbnb doesn’t own any of it.

For a deeper understanding of aggregators, Ben Thompson’s Aggregation Theory is a great place to start; to understand what we mean with “owning” the supply side this post by Casey Winters can shed some light.

On the bottom layer of the triangle sit the infrastructures: the AWSs, the Twilios, the Agora’s, the DHLs of the market: behemoths that wrap real-world infrastructure and make it consumable, modular, ubiquitous, and cheap, effectively enabling more aggregation to happen, more products and services to be created and marketed.

Competing at the different layers

Competition follows very different rules at the different layers. On the top, nicheness trumps everything else as the market always offers new ways for specialized providers to find their fit. At this layer talent and reputation are leveraged, and – to really thrive – you’ve to be small, nimble, focused, and passionate about what you’re providing on the market. Competing on the top of the triangle it’s hard for large companies: in case they want to compete there, they likely have to empower their smaller internal teams to do so, no bureaucracy can really compete for that part of the market. In this part of the market uniqueness and quality make a difference, and the trend goes along: as transaction cost goes down, competition goes up and the optimal size to compete on that market just…continuously shrinks.

To compete at the aggregator layer rules are radically different: here the size of the network makes a clear difference in terms of value perceived by the customers: this is what we call network effects. The more nodes in a network the more value is perceived as a new participant joins the network. Network effects have multiple facets – we largely covered the powerful flywheels that these network effects put in motion in this piece – but the essentials are:

- basic flywheels, that are either one-sided or two-sided, with two-sided meaning that two different roles can be played in the network and the availability of one attracts the side in (imagine buyers and sellers);

- reinforcing flywheels, that create further defensibilities as the value proposition gets reinforced due to additional advantages that are connected with growing size. Examples are: developing a particular capability to help customers find the right providers based on previous transactions data, or even just an improved brand perception as customers associate brand with a guarantee of finding the right solution on the marketplace.

Competing at the infrastructure’s layer is even harder: economies of scale tend to compound very strongly especially if the deployment of new, real-world infrastructure (with relevant CAPEX) is needed to stay on top of demand. It’s easy to imagine that building the right infrastructural capability from scratch to compete with, say, Amazon Web Services would be a tantamount challenge even for the most capitalized of entrants.

So what does this mean for value propositions?

After having reintroduced a clear breakdown of the market layers (niche player, aggregator, infrastructure) and – before that – having borrowed from a16z the list of four key needs of niche producers (accessing customers, accessing partners, accessing capital, and managing the key elements of the business process) let’s now look into how this relates with Value Propositions.

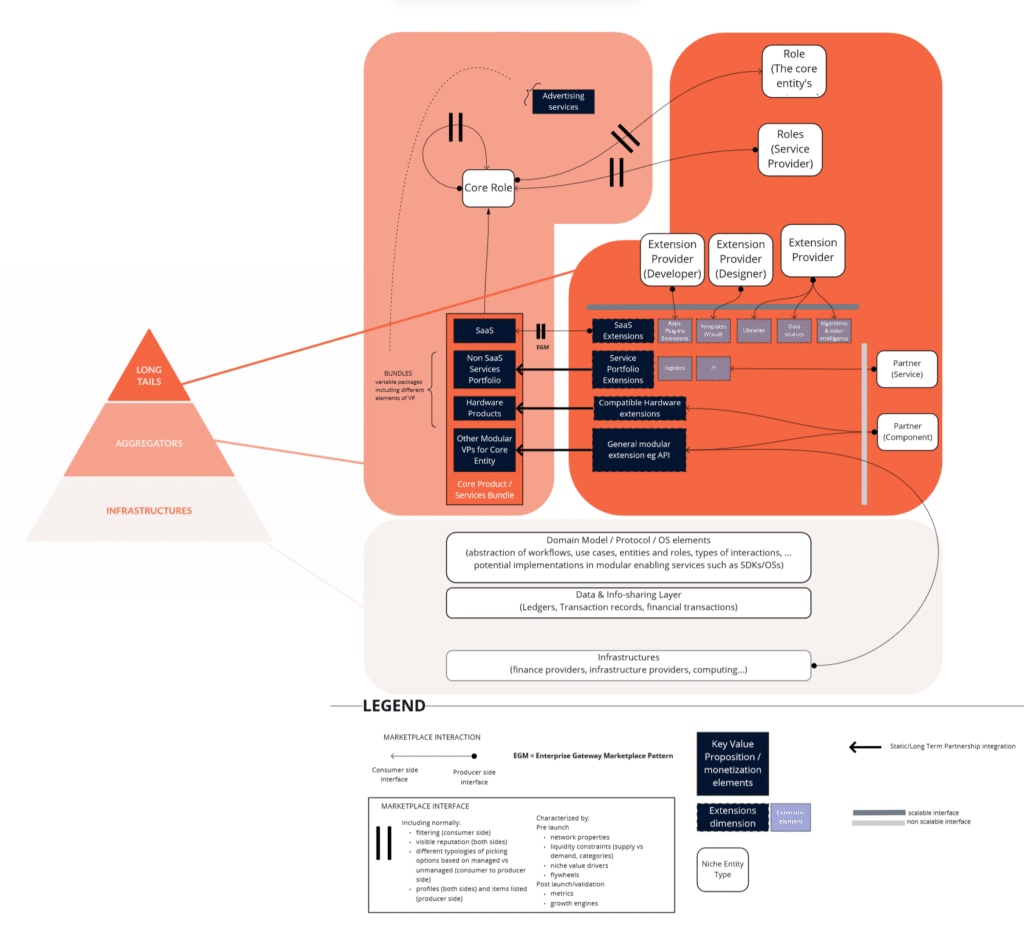

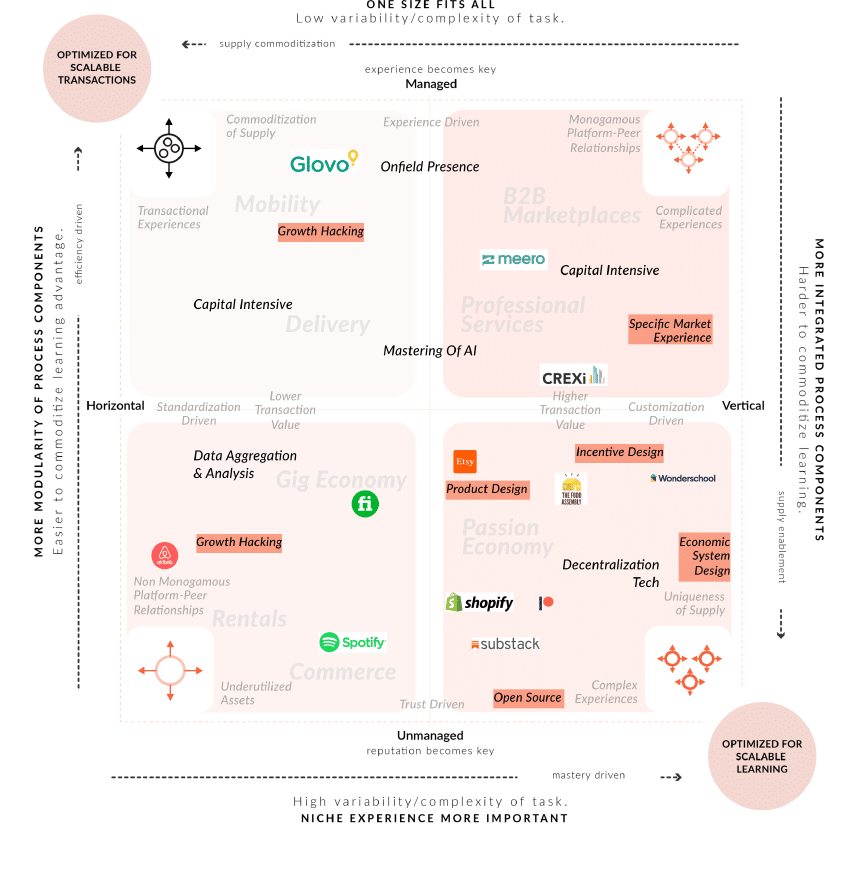

The picture below provides a breakdown of the key elements of value proposition one can create on a digitally enabled market (essentially any market at today) and the colors in the background show you who’s the type of player supposed to provide such elements.

Please note that by clicking on the picture you can open a large PDF version. We’re going to keep this model handy for the rest of the piece.

Value Proposition 1 – Building the product-side: managing the key elements of the business process

Despite the name “aggregators” make one think only to the capability of connecting supply and demand – or more generally connecting the nodes in a network – aggregators today almost universally offer a strong product side to their value proposition. There are at least two main reasons why this happens: bootstrapping and evolution of marketplaces.

First of all, to perform network bootstrapping, having a single-player mode / single user value proposition (a value proposition that is attractive to only one customer, irrespective of the network she’s connected to) is essential to attract the first users to the network. Aggregators normally do this in the hopes that the first critical mass of users will generate a self-sustaining growth flywheel that will gradually compound. The most common pattern here is:

- attract the supply side (normally more professionalized) with a strong and accessible, often SaaS-based, implementation of a back office for the most common workflows and basic use cases that such professional is dealing with;

- as a result of attracting suppliers be later able to attract customers and generate liquidity (a working balance between supply and demand), solving the chicken-egg problem.

The fact that most of the time the product side of the value proposition is targeted to suppliers is a consequence of a common rule of thumb of marketplaces: in building one you’re normally supply constrained (it’s harder to find suppliers than consumers) and therefore you want to attract suppliers first to assess the feasibility of your endeavor.

Some clear examples of aggregators with a strong product side can be found in:

- Shopify’s e-commerce store management tools;

- Airbnb’s booking management system;

- Salesforce CRM offering.

It’s important to acknowledge that such product side shouldn’t be considered just as a SaaS: product sides often involve more general service bundles, can involve hardware products and other modular elements of the value proposition, including financial services such as small loans.

Some good examples are Slice Accelerate a full stack marketing and productivity solution for pizzeria’s that has been able – according to Slice – to double sales and increase new customers’ acquisition by almost 60% in the shops that adhered. In this case, Slice effectively bundled a booking SaaS and POS with a bunch of advanced services that an average pizza shop would have had possibly hard times in sourcing on the market, for both price and discovery, or maturity issues.

Managed marketplaces and Marketplace as a Product

From another perspective (more consumer-driven), since aggregators have to outcompete traditional industrial incumbents their customers expect high replicability and high-quality services that may be problematic to provide simply through intermediating providers.

As a result, aggregators have evolved to ensure their suppliers can be more consistent in delivering the value proposition. To do so, they don’t just provide suppliers with a common set of enabling tools: in some cases – with the so-called managed-marketplaces – they push into further integrating and embedding suppliers inside a product offering, effectively removing the need for customers to filter, and choose what provider to pick (think of how Uber never asks you to pick your driver but, instead, picks her for you) or even subsidize supply (or demand) very strongly.

Some clear examples of managed marketplaces that oversee and productize much of the experience:

- Opendoor’s: in the “sell to Opendoor” option, the aggregator effectively plays the “demand” side of the marketplace, buying the houses directly from the sellers

- Auto1 Remarketing option helps car dealers with elements of their portfolios they are having hard time selling, to auction them to a network of dealers through sales managers;

- GOAT’s resale option includes an authenticity verification service, where GOAT verifies the authenticity of the sale before sending the items to the buyer.

To understand better the evolution towards managed marketplaces, and why that happens we suggest you to catch up with:

Dan Hockenmeier’s take on Super Suppliers on The future of marketplaces: coordination, capital, and creativity

Chapter 2 of our Whitepaper: “New Foundations of Platform-Ecosystems thinking” where we cover this evolution in due details (see our marketplace map below)

Value Proposition 2 -Accessing Customers and partners through marketplaces

Of course, besides the product side of the offering aggregators do what they’re mostly supposed to do: aggregate. As we’ve seen above, the product side of the offering is normally targeted to the suppliers, but we can generalize it considering that the aggregator will target the product side to the “core role” of choice.

Two major patterns exist in marketplaces then: solving the core customer’s need of finding its customers or that of connecting to peers, providers, advisors, and consultants, respectively identified as demand generation in and online communities in the a16z breakdown.

Examples of such are clear and abundant: anybody that booked a room on Airbnb can – of course – relate with the demand generation marketplaces where customers of the aggregator (hosts) are in turn connected with their customers (guests), but it’s easy to spot on the wild also the pattern of connection with other types of service providers.

Some examples are:

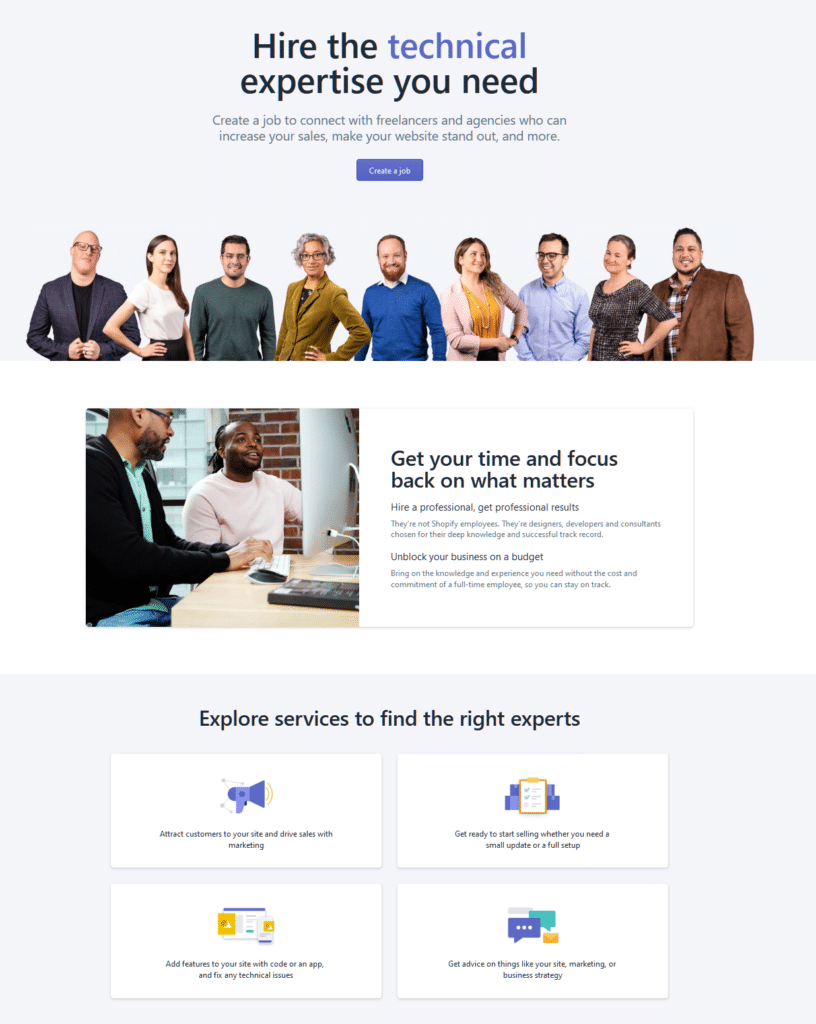

- Shopify’s experts marketplace

- Salesforce’s Appexchange Consultants marketplace

- Thinkific’s expert’s marketplace](https://www.thinkific.com/experts/)

- Mural’s Playmakers

Value Proposition 3 – A mix of the two worlds: extensions platforms

Finally, the third key element of the value proposition that can be developed in this context is that of so-called extension platforms. The term “extension platforms” is something we borrowed from Casey Winter.

In Winters’ framing, the evolution of a SaaS into an Extension Platform starts from what Winters calls an “integration platform”. The idea is simple: as you create a SaaS product (Winters’ analysis is essentially focused on SaaS) it’s ok to provide a core set of functionalities, but, in the long term it will become essential that you create the means, the context and the incentives for your product to connect and integrate with the other products that the customer is possibly using as a complement and extension of the features your product provides.

In Winters’ words you start from “integrations” intended as somewhat costly, one-off processes to integrate other products’ user flows into yours, enhancing data and feature integration. Later you evolve your product stack towards being ready for “extensions”: extensions are supposed to be scalable and – on the contrary of integrations which require your direct intervention – extending should leaves the third party in charge to use published and open interfaces to your product to integrate autonomously.

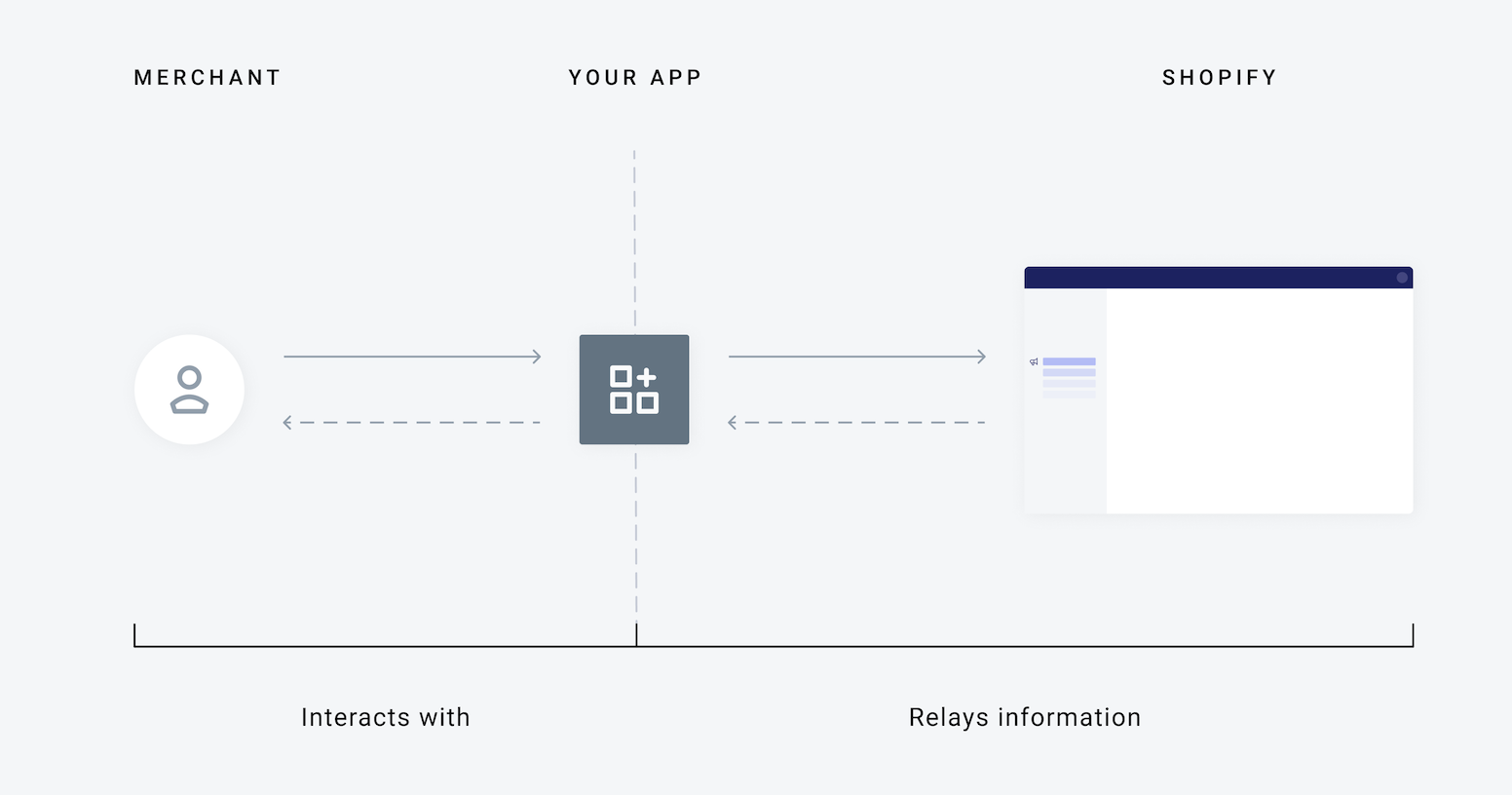

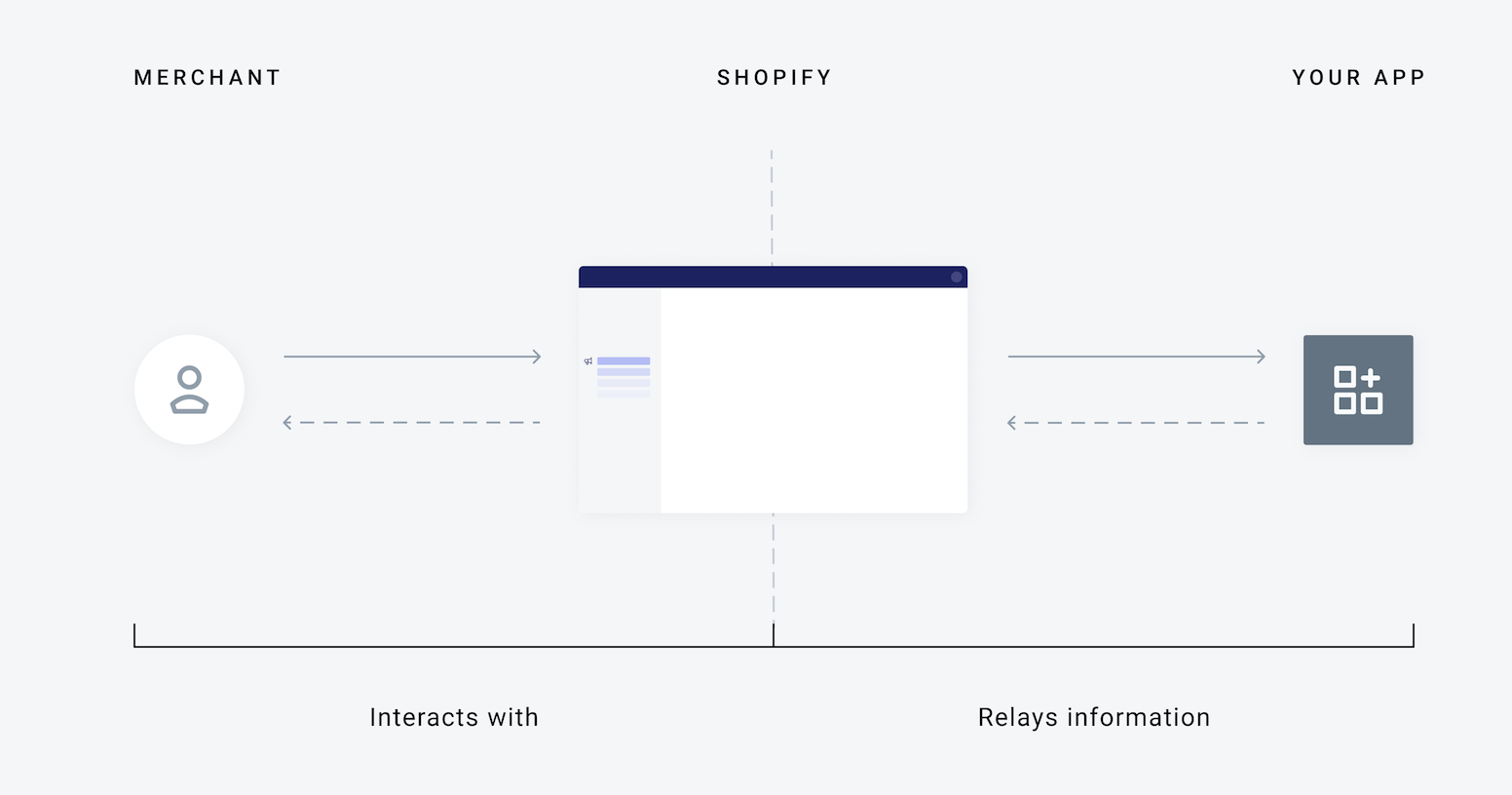

If we limit our thinking to SaaS, the idea of “extensions” easily maps with the following patters: plug-ins and apps. In Shopify’s terms extension are framed a bit like “reverse APIs”: as one can see below (images from Shopify’s developers portal extension overview), in a traditional API integration pattern the user would interact directly with the external app and the app would be responsible to “call Shopify” for information. Instead, in an extension paradigm normally the user experience is centered around the SaaS you’re providing to the customer and the extension (the app in this case) is called for data that is subsequently reintegrated in the main user experience. One can think of a similar pattern also with Amazon Alexa’s Skills.

Besides details of integration and user experience – like in the concept of apps – if we stretch the thinking a bit we can see also how other types of extensions are possible:

- templates, providing visual customization (a la WordPress);

- libraries of elements (such as Figma’s files)

- data sources, providing further information for intelligence (such as adding a meteo data source for a travel intelligence product);

- algorithms (imagine adding algorithms to a car diagnostics software)

and much more.

All these extensions effectively extend the functionality of the SaaS, not by integrating features from other contexts of the business process, but more from the perspective of enhanced choice and personalization.

Depending on the nature of the core product extensions can of course be of a different kind. For a core product value proposition based on a portfolio of services, particular services partners could be seen as extensions. A typical pattern in this sense could be that of integration partnerships: think of partners that can help your customers install and maintain a certain product, add logistics capabilities, or any complimentary services.

In the case of a hardware product, such as with the world-renowned Arduino IoT platform, one can think of extensions as compatible pieces of software such as so-called expansion boards capable, for example, of multiplying I/O channels for further developments. In case we think of more of a consumer-grade hardware platform such as Google Home one can think of the plethora of devices that have been developed and marketed offering compatibility with BigG’s Home platform.

Clearly, the more primary customers do your product plus marketplace value proposition attracts, the more third parties will be attracted to develop extensions to reap the benefits of reaching a huge user base.

To understand better the importance of extensions in developing a convincing value proposition for your product we suggest you to read Kevin Kwok’s excellent primer covering Figma’s and Canva’s approaches at building scalable and ultra personalizable products, leveraging on community flywheels.

Evolving from one value proposition to another

Complementing something that starts as a single product strategy with a network based experience – being it a marketplace or extension platform – can be an essential strategic advantage. Networks can drive growth in product adoption and produce powerful innovations in terms of product adaptation – through extendibility.

As the gradual evolution of the market pushes more into vertical and managed contexts, where the platform provider oversees more of the experience, a “product” side to the value proposition is central, and not just a growth hacking technique for the early stages. As the platform economy moves into more business-related contexts, professionals are more likely to choose products that support their business process beyond pure lead generation, and thus the product side may become even more important.

The evolutionary pattern can start from a network value proposition and later evolve to integrate a product value proposition (like with Slice’s evolution into Slice Accelerate). In other cases, the direction is just the other way around (a la Opentable).

According to Eventbrite’s CPO Casey Winters: “if a business starts as a marketplace, it usually means demand is the most important problem customers need to solve”. In an attempt to generalize this mental model we can provide a recap schema as it follows.

If one starts with a SaaS (or more generally a product side offering):

- it makes sense to evolve towards an extension platform strategy if customization is an issue: especially in the case the workflow/business process is complex and needs much customization;

- it makes sense to evolve towards a marketplace strategy if access to demand or other sides (suppliers, consultants, advisors…) is an issue thus making the case to create aggregation.

If one starts with a marketplace offering, it makes sense to integrate a strong product (eg: SaaS) offering to respond to potential competitive pressure and keep the core users’ side (normally suppliers) loyal.

Nuances of this SaaS/Product to Marketplace/Extension-Platform pattern, are common in many recent success stories: from Android to Figma, from Salesforce Appexchange to the already mentioned Opendoor.

For all these reasons, embedding in our new theory of marketplace-platform growth key elements of product thinking is crucial.

The Domain Model and the Info-Sharing Layer

To properly close this reflection on building strong value propositions in a business ecosystem we have to spend a few words on the most basic layers and on the new developments that the technologies related to web3 are bringing to the table – a deeper analysis of the topic will be featured on another piece.

Of course, any platform strategy we develop will be always based on two essential layers:

- an ontological abstraction of the domain, something we could call a “domain model“, a “conceptual model of the domain that incorporates both behaviour and data”;

- a data and info-sharing layer where all data is stored according to the domain model above (as a representation of the “state”).

Typically, web2 platforms control the full stack: they not only provide the core product, but also control the marketplace and the extension platform (in case they’re present), by vetting all participants, assigning reputation, policing, and connecting with end customers. In this model, the Domain Model specification is normally all internal and not opened to third parties to interact with, and the Info-Sharing Layer is normally based on internal databases that leave no transparency, access or portability of data whatsoever to third parties.

Thanks to a burgeoning web3 initiatives space, such an approach to the stack is increasingly being challenged in the direction of an unbundling of the underlying layers (often called “protocols”, see Sangeet Choudary’s recent post on the topic) and the rest of the aggregator’s stack.

It’s important to clarify that, even if we believe in the new capabilities that the web3 is bringing up, this doesn’t mean aggregation won’t be needed anymore. The user experience will always benefit from centralized access to the inventory through filtering; network effects will always play out increasing the value of joining lively communities, but we may well face a future when different players can build competing strategies and contribute to an ecosystem where more options are available and its increasingly difficult to leverage on defensibility strategies premised on network effects or lock-ins.

If – as it seems – open and permissionless layers of data, based on protocols and domain models that are shared and co-developed by many, will emerge, this would likely lead to:

- different aggregation strategies to emerge that compete on top of a shared layer with no concerns of censorship or conflict between the platform owner and the third parties developing on top of it, due to open interfaces and shared ownership of the underlying layers;

- niche players becoming able to perform across different aggregators with much more ease, possibly leveraging on common reputation and verified, and sovereign identities (elements of the stack that also subject to unbundling and portability) stored on top of a public blockchain.

One thing that we may assume though, even in the presence of a widespread unbundling between these layers is that the key roles structure (niche player, aggregator, infrastructure) will likely continue to exist, even if unbundled and more plural. Acknowledging that markets are going to continue needing such a specialization of roles, doesn’t mean the impacts will be limited. As we are seeing already with pioneers in DeFi, but also in web3 marketplaces such as Braintrust or even infrastructures such as Dimo, new institutional forms, new organizational agreements, new governance processes are emerging that feature non-profit foundations leveraging non-equity bearing service providers, mixed governance mechanisms involving on-chain and off-chain democratic voting, and even an evolution into economies fully denominated in internal currencies.

Conclusions

We are at the very early stage of a process of evolution, and web3 new patterns can profoundly reshape how digital markets behave: this evolution will lead to less competition and more cooperation and ease the creation of last movers that achieve transformative impacts on entire industries. Despite this, basic patterns of value creation, and three types of value porpositions (product, marketplace, extensions) will stay: to enhance your chance of finding your place in an ecosystem you’ve to understand these basic elements and – at the same time – be prepared to embrace radical new patterns and integrate them in your strategy from the start.

Are you curious about developing mastery on the application of such techniques, access our beta tool releases and more?

Join us at the upcoming Platform Design Bootcamp in June:

Before You Go!

As you may know, everything we do is released in Creative Commons for you to use. In case you’re getting value out of these reads and tools, we encourage you to share with your friends as this will help us to get more exposure, and hopefully, work more on developing these tools.

If you liked this post, you can also follow us on Twitter, we normally curate this kind of content.

Thanks for your support!