Visualizing a Product Portfolio Strategy on a Wardley Map

In this article, we explain how to visualize a Portfolio of product/platform strategies on a Wardley Map (an abstraction of a value chain that considers the evolutionary stage of all components) and what advantages this can bring.

Simone Cicero

Prashanth A

Luca Ruggeri

Emanuele Quintarelli

This post has been co-developed through fieldwork and analysis in collaboration between Boundaryless and a Team from Bosch India working on Digital Solutions for Mobility and has been co-edited by Simone Cicero, Luca Ruggeri, Emanuele Quintarelli, and Prashanth A.

Abstract

The need to articulate a portfolio of product strategies is gaining importance as organizations are forced to deal with the increasing modularity and composability of markets in general. Visualizing the portfolio of products that your organization is bringing to the market is essential to evolve a strategy around the interdependencies and interactions between the building blocks. Doing so is critical to optimize your go-to-market strategy, the adjacencies/complementariness of products, and many more relationships across the organizational framework. In this article, we intend to share in detail our experience in representing product portfolios on a Wardley map. In our previous essay titled “Framing a Portfolio of Platform-Ecosystem strategies inside an Organization” we introduced a complementing method, based on a visual representation that allows arenas and platform strategy models to be visualized in a web of functional relationships – something we normally call a “Portfolio map”. Such a representation connects arenas of exploration with the product and platform strategies that the organization is developing. A complementing portfolio representation based on a Wardley Map, we argue, can make it easier to execute key actions that are more related to the go-to-market challenges and other key elements of the strategy. These include the ability to enumerate, typify and visualize what ecosystem entities the portfolio does target, clarify product taxonomies and lifecycles, and evaluate opportunities through scenario simulations based on assuming the impacts of a certain move on all the pieces of the portfolio.

Your organization’s future is about diversifying products

If we acknowledge that small teams are becoming more capable – essentially thanks to wider accessibility of a full stack of enabling elements, services, and infrastructures that can be used to create and scale both digital products and services – we are ending up in a much richer and composable market/ecosystem. It would be then a net loss for companies not to acknowledge this and prevent the organization in a too-reductive scope, hindering creative entropy, innovation, and entrepreneurship.

In a market and organizational landscape such as the one that is unfolding, interactions between different pieces of our own offerings as well as interfaces with third parties that either use ours or provide their elements of value propositions enable the creation of more comprehensive offerings needed for customer scenarios (complex customer journeys, coming together across different products)

As a consequence of such evolution, embracing a product-centric operating model provides substantial and growing advantages to companies and is a strategic element that companies can’t afford to ignore anymore.

The general problems of managing portfolios

Organizations that have developed or want to develop the maturity to run an unbundled products portfolio strategy – which is one of the key three problems of becoming “platform ready” – generally deal with several common challenges.

The most recurring problems are the ability:

- to strategically frame the operating boundaries of the existing portfolio

- to recognize the friction points across the operating boundaries and translate them into opportunities

- to understand where the company could be actively pursuing a new product strategy;

- to filter out incoming opportunities and choose what to pursue and what not to build;

- to decide the nature and scope of how the ecosystem can complement the product strategy;

- to define a macro, portfolio-level strategy that involves the whole of the portfolio as a combination of multiple portfolio elements;

- to understand how alternatives or adjacencies of certain portfolio elements are emerging from the market and evaluate the impacts.

Part of the work needed to respond to such challenges is about the capability to visualize interactions between portfolio elements and play scenarios that could unfold as a result of the potential application of certain strategic plays. An example could be answering questions such as: “what happens if we open up and provide as a service this particular component of our product portfolio?” or “what would be the impact on competition and on the arena in general?”, and “What impacts could we expect on this particular piece of the portfolio?” “Given the interdependencies observed, how would a service/component evolve given the usage patterns etc…”

Another aspect of the work is to enable the setup, and how to actively facilitate the self-organization of teams, and organizational capabilities, around certain pieces of the portfolio, so that new teams are empowered to develop new pieces of the portfolio, or to work on general capabilities that could be optimized. Typical questions regard

- understanding where to draw the lines of a separated P&L around a certain product or division;

- defining either hierarchical or bundling relationships or open interfaces between products;

- drawing a framework to incentivize new interactions in a way that they are solution-centric or platform-centric or building-block centric

- understanding where to extrapolate common needs into internal enabling platforms;

and more.

Using a Wardley Map to represent a Portfolio

Wardley maps are already part of the Platform Design Toolkit practice as a key piece of our exploration and design methodology. In the usual case, we use Wardley maps in combination with our library of “platform plays”, common visual transformations of recurring value chains that one can use to be inspired – when looking at a value chain (most likely an industrial one) – and trying to transform it into a credible platform strategy model. These “platform plays” help designers identify what to bundle in a product/service offering, what transactions to standardize between entities in the ecosystem, what type of identities and reputational elements to make explicit, and more.

When it comes to identifying a platform opportunity we normally explore the ecosystem starting from certain arenas, through deep ecosystem scanning practice that helps us plot all the players, mediators, and components, and then represent it on a Wardley map on top of which we later apply platform plays. These recurring strategic plays can help us transform the industrial value chains into platform-mediated ones.

When we deal with portfolio mapping, instead we’ll likely represent the market as already transformed by our products, and – furthermore – we’ll have to represent different products on the same synthesized overview. Many times, we might already have partially unbundled our products as we proceed to represent them, other times we could actually use the map to simulate the effects of unbundling and re-bundling.

To get an easy-to-relate example, look at the picture below, where you can see a relatively high-level representation of (part of) Amazon’s portfolio on a Wardley map where five of its products are represented.

Identifying leverage points, defensibility points, and network effects

Once a portfolio gains visibility on a Wardley map it’s easier to identify a series of key elements that could make a difference in an overall portfolio strategy. For example, the plot will likely present elements of the portfolio that exist at a genesis/custom-built stage of evolution, essentially something that your organization is developing with a unique and novel approach. These elements lend themselves to be considered core innovations that hold a promise of – if kept unique – providing a unique market positioning.

Other pieces of the portfolio may be more commoditized or productized but at the same time may provide certain defensibilities due to having accumulated network effects, or other moats related to technical, scale, or brand defensibilities. Another important piece of information that you can represent on such a portfolio would be if a particular element either has or does not have access to the market.

In the picture below we can see how:

- most of the products in Amazon’s portfolio have been granted access to the market directly: for example, a third-party e-commerce website could use Fulfillment By Amazon (FBA) even if this means directly competing with Amazon Marketplace

- Some of them present relevant defensibilities, for example, FBA (technological and scale defensibility due to the development of infrastructure and process), or AWS.

- some of them have succeeded or can succeed to create network effects and therefore maintain a certain differentiation in the market even if available at the service/commodity stage

- some other products – in this case, Amazon Basics don’t provide any specific defensibility and are also “bundled” with another product (see the ticker line) – you can find Amazon Basics only on Amazon.

Once you’ve developed such a visual representation of the market you can play many scenarios. Some could be as easy as

- playing with the idea of bundling or unbundling products;

- launching a new product that can piggyback on another’s defensibility or network effects through embedding

- creating nodes, interfaces, repositories, exchanges, and protocols to enable the opening of the ecosystem for players hitherto excluded due to lack of access

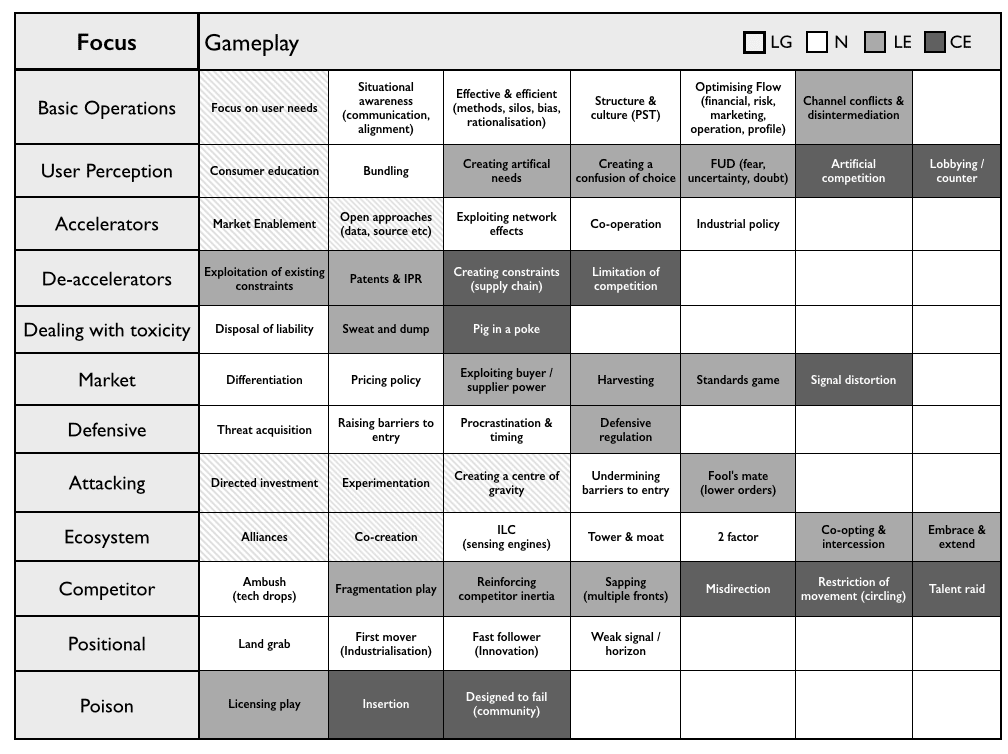

and other more complex/comprehensive ones. While the set of strategies and gameplay you can play on a portfolio is essentially endless, we can piggyback again on Simon Wardley’s work also when it comes to picking from a – quite extensive – list of gameplays: he actually listed 61 gameplay elements you can start from (list from 2015).

Despite all being extremely interesting, as you use a portfolio representation for innovation, you may find the positive ones as the most useful. At least explore the following categories:

- Accelerators (enablers of acceleration of the process of evolution)

- Market (standard ways of playing in the market)

- Attacking (standard ways of attacking a market change)

- Ecosystem (using others to help achieve your goals)

may be a good starting point for inspiration. The point is, in any case, that: visually playing with your portfolio as a strategy team will give you a much more solid and shared understanding of your potential ways to strategy. Below is a schema that covers the whole set of Gameplay.

Other key reflections that a product portfolio on a Wardley Map can help you make

Besides strategic considerations on where defensibility sits in your portfolio and playing go-to-market related scenarios together with other strategic considerations, another key potential use of a Wardley map-based portfolio representation is to be conducive to actively informing your choices when it comes to

- framing the scope of play for the company

- seeding a new team to develop a lacking portfolio piece;

- selecting partners or evaluating “buy” or “rent” options for key enabling elements;

- abstracting common enabling services into shared services platforms;

and more. Actively seeding new product teams is indeed essential to be able to re-bundle existing portfolio elements or develop new ones, in a direction that enables new customer scenarios/journeys. As you do that you’ll have to consider if that particular portfolio piece can instead be provided by an external partner, or sourced on the market through a supplier. Before considering actively investing in a new team to build a new piece of the portfolio, an organization must at least ponder how this new team could gain market access and if this makes sense at all. Sometimes new portfolio elements have a solid overlap with the organization’s mission, it’s brand and may also have the potential to leverage a spillover growth effect from a pre-existing piece of the portfolio. Imagine for example how suppliers on the Amazon marketplace are the ideal customer of the FBA service: they’re already selling on Amazon, and you already identified their need to offload the hurdles of managing the logistics of fulfillment on their own, and therefore this makes it a no brainer to create such a new product for them to enjoy as you’ll also have the possibility to leverage on your existing relationships in the moment of launch. Once you’re at that: why not open FBA to other potential customers? In this case, we’re talking about sellers already running their own e-commerce site or even other marketplace owners that want to provide a similar service to their own sellers (as for example with third-party drop shipping providers).

Clearly, a portfolio element that:

- has a strong overlap with the mission;

- can have a market interface on its own;

- has the potential to enjoy a spillover growth effect;

- has the potential to be sold on the market on its own;

- has the potential to include competitors in the market/ecosystem;

is an ideal candidate not only for being an addition to the portfolio but also to become a new product-micro-enterprise that can develop its own leading market targets, and sport a team that can be made to bear skin in the game. Indeed, it’s important to understand that you can create micro-entrepreneurial teams where you have market access, and where you don’t have other strategic implications that would justify hierarchical, portfolio-level choices.

While it is generally safe to assume that all portfolio elements should develop their own product strategy there are some major questions to keep in mind that would justify avoiding exposing a certain product/module interface to the market. First, a key consideration is to be entertained when thinking about externalizing so-called platform teams, or more in general shared resources and shared enabling portfolio components (those that support one or more upper-layer strategic products with key services or components) and that are not yet available as a commodity in the market yet.

If we externalize and open such elements in the market we could end up in a situation where their market optimization (for example maximization of usage of their internal resources) may end up reducing their responsiveness to the other portfolio players relying on it, overall reducing the company’s capability to develop an advantage versus the competition (this has been excellently covered in Expertise And The Shared Services Problem: A Conversation With Don Reinertsen).

Furthermore, strategies that seem functional and positive for a particular product can generate systemic impacts that end up damaging or at least not leveraging on other portfolio elements. A typical example could be where your company is currently successfully selling a bundle of hardware and software. Let’s say we capture a market signal that the services market that is growing around the product is making up an interesting market opportunity and we decide we want to develop a platform strategy on top of the basic product. So we end up considering developing a services marketplace for service providers that can provide complementary services on top of the software. In the process of bringing this to the market, we are tempted to provide the software as an open operating system so that more market players would be able to use it to create their hardware products, with a software stack that is compatible with our services marketplaces. If we unbundle the software and the hardware in the process and we make the software open source, the effect on the hardware is as well that of a commoditization: overall this may end up being a wise choice for the organization (if the services marketplace turns out to be profitable, and providing higher marginality) but the net effect on the hardware product unit would be that of putting them in direct competition with multiple other hardware providers. These dynamics of the portfolio map when captured visually enable the actors in the ecosystem to actively look for relevance/differentiation in their arenas.

Another point to note is that the margin pools in such ecosystems get distributed over time due to interventions in the form of regulatory policies, technology disruptions, and consumer preferences. Such visualizations help in simulating the potential nodes that can be subject to such forces of the ecosystem or in some cases showcase opportunities to shape the whole arena. These methods and tools provide your company with an opportunity to frame the ecosystem, simulate with constraints/leverage points and allow the evolution of strategies for the effective allocation of capital.

There’s a great story we often use to explain how – despite the driving force that should guide your strategy in a modular market is that of unbundling – understanding complex portfolio interactions is essential to produce a sustainable strategy: that of Google’s Android.

At the time of launch, Google originally launched the Android OS as a fully open operating system: within time, their strategy shifted with the aim of – on one hand, keeping the user experience consistent – and, on the other, protecting their key revenue streams, such as the take rates they exert on in-app purchases.

As a consequence, Google first unbundled the most basic elements of the OS and called it AOSP (Android Open Source Project) and then rebundled their Google Play Store (where they accrued network effects in the form of app developers and app users) with another component of their portfolio, an (at that time) obscure module named Google Play Services. Google Play Services is effectively a container of most of the developer-facing value-add services that Google provides for developers to write scalable and reliable applications such as in-app purchases, notifications management, location access, and much more) but also bundles most of the core Google apps, with AOSP.

In this way, if a third-party OEM wanted to develop a proprietary developer services platform it would – most likely – end up losing compatibility with most of the apps in the Store. For more information about the topic check this post How Open-Source Is Android Really?.

Conclusions

Building capabilities to manage a portfolio of products strategically in your organization is becoming increasingly essential as companies are increasingly required to develop multiple value propositions in combination with partners and leverage market-available components. Portfolio framing and management are also critical to choose what new teams and units to seed, how to resolve conflicts between product-unit strategies, and more. If coupled with a deep opportunity exploration work, and with an organizational model that actively encourages team restructuring around opportunities to develop the portfolio your organization can become nearly unstoppable on the market.

If you want help understanding how this approach can be implemented in your organization please reach out via the form below.

Do you want to learn how to frame your product to resonate with your Ecosystem? Learn how to design platform strategies with us at the Platform Design Bootcamp coming up in April.

Join us at the upcoming Platform Design Bootcamp:

Simone Cicero

Prashanth A

Luca Ruggeri